Goodbye From this River: Romeo Oriogun Remembers Binyavanga Wainaina

Photo by Beowulf Sheehan

To pay tribute to iconic Kenyan author and LGBTQIA+ activist Binyavanga Wainaina, who passed away earlier this year, PEN America reached out to Nigerian poet Romeo Oriogun, who wrote the moving piece featured below: “Goodbye From This River.” Wainaina, a participant of the 2015 World Voices Festival, leaves behind a legacy of literary excellence and unwavering support for the LGBTQIA+ community.

Dear Binj,

I am far from home. The grasses having survived the cold of winter are praising the god of spring with their lushness. Some days I walk along the bike path opposite my house, smoke a blunt as I praise the earth for the bodies of cyclists and joggers passing me. Some days I play a game: I look into the faces of black people and try to match to them the faces of my friends at home. Did you also feel out of place in cities that were not yours? Did you also search faces for home? Today I am walking to the river, a white ceramic bowl is hidden in my bag, there are also some bananas, some cowries, a stick of candles and some quarters in it. I have been doing this a lot, first for Chukwuemeka Akachi, then for my parents, then for Jay Jay Blinks. For everyone I know the earth took from my arms, I say goodbye by telling the river to guide and protect them as they journey home.

I solemnly swear that I do not know you.

I have had several opportunities to meet you. I have in a time of need received guidance from you through Whatsapp messages. I had watched you from afar and have read everything you wrote that was published on the internet. I was at Ijebu-ode, a small town in Ogun State, when I first read your viral piece “How to Write about Africa.” In the dark, I read it on my phone and laughed. I laughed not because it was funny but because you’ve found a way around language, a way to write our pain and anger through humor.

Photo by Molly Leon

In the years that followed, I read more of your essays. I, who wanted to enter the priesthood, who found a sacred order of men who have vowed to die single, an order of men who prayed their desire for sex through the rosary, a cure for the hunger ravaging my body. I, who for every time I lusted after a boy, ran a blade through my flesh. I, who saw the man in torn denim pants resting on the kiosk on the street just after Awodi-ora Estate, his eyes closed. I, who went close just like others to see what was happening. I, who saw the blood and knew he was dead. I who listened as a woman shook her head and said “Na only people wey dey possessed them dey fuck for yansh.” I who ran home and washed and washed my body so water could separate my name from his, so my fears won’t lead me to confess to Preye who own the room I’m squatting in. I who listened as this nameless man was denounced as a sinner in death. I who lived through nights afraid of what mornings might bring was not ready for your lost essay.

Photo by Beowulf Sheehan

I had discovered Essex Hemphill before your essay was published. I found his book in a pile of used books for sale by the roadside, just opposite the University of Ibadan entrance gates. Its title Ceremonies called me, and I responded. I read his poems at my siblings’ apartment and cried, not because I was sad but because for once someone saw me, someone prayed for me, someone gave me a language to write my joy, my hope, my fear, my life in the dark. For once someone saw the weapon I needed to fight. He stretched his black gay hands from across the ocean and gave me his poems. Almost in every poem, in every story, a straight man is writing about his love, he is calling out his lust without fear. I had read poems published online by heterosexual Nigerian writers on homosexuality; I have read Jude Dibia’s book, I didn’t know why they were appealing to be understood. I was angry about the constant need to explain “the homosexual desire.” I needed something that said: “This is me in all my fear and glory.” I needed something that said my body is at war and heterosexual Nigerians are the enemies. I wanted them to see my body for what it was: a being threatened by an environment created by colonization and further threatened by the religion The British Empire left behind. Essex Hemphill gave me that, his poem “American Wedding” was a testament to life. Every morning I would read a poem by Mary Oliver and then read “American Wedding.” I would recite the following lines.

“They don’t know

we are becoming powerful.

Every time we kiss

we confirm the new world coming.”

Binj, in those lines I would see hope. I would see my black body raised high above what dreamt to kill it.

Binj, if Essex Hemphill gave me poetry to stay alive, you gave me a language to reach to my dead mother. When I read your essay “I Am A Homosexual, Mum” I saw myself as a child kneeling before my mother’s death bed at The Anglican Maternity Hospital in Benin City. Three days before she died, she will hold my head and look at me with her jaundiced eyes, she will say “Omoregie, I’m sorry I won’t be there for you. You will suffer.” I will laugh and tell her she’s joking again, just like she was always joking that one day we will leave and never return. Binj, your essay took me home and I followed you until I was wrecked with a desire to tear out my heart. Binj, I saw myself at the end of your essay whispering “Mum, I don’t what I am, but I am not straight.” I was still figuring out what language is my desire. When I wrote in a poem that I am black and bisexual, I was speaking to the mother your essay led me to, I was seeing in her eyes a permission to live, to love, to be who I am. You gave me a language that is brazen, that is without shame, that is human.

Once in the food court at Freedom park in Lagos, I was sitting with Chris Abani and Igoni Barrett when a young writer approached Chris Abani, she like all of us was full of happiness to meet him. I think she was carried away and wanted to impress him. Who wouldn’t be? Chris Abani was a myth to us, his poetry was different, his novels challenged the way we thought about masculinity in the Nigerian novel. She talked a big game and I watched Chris smiled and I listened as Igoni said “the only way to know a writer is through his writings.”

I solemnly swear that I know you.

The river is cold. I place one leg in it and say, may water lead you home, may your tutu not be caught by a stay branch, may you dance into your mother’s hands. I say, may what you left behind give another lost boy a language to reach what is beyond him. I say, live. From my bag, I bring out the ceramic bowl, I place the bananas, the quarters, the cowries and the candle in it. I give them as an offering to your body passing. I give them as an offering to an ancestor that left stones in the river to guide us home.

Binj, goodbye from this river. May every shore you touch give you what you will demand to lead you home.

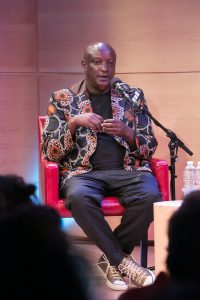

Binyavanga Wainaina and Chimamanda Adichie at the 2015 World Voices Festival. Photo by Beowulf Sheehan