After more than two decades at The New Yorker and The Atlantic, George Packer learned exactly how to keep his readers curious and informed about American culture and politics.

At least until 2022. Around that time, Packer noticed that his profession was starting to deliver diminishing returns. “For a while, facts had lost their power not only to change people’s minds but to tell them what was real,” he said. “We each had our own facts, our ‘alternative facts,’ and they kept pouring in.”

Perhaps, Packer thought, he could render the world more clearly to himself and his readers if he took some distance from it. “I just needed…to cut away the overly familiar names, places, issues, arguments that begin to numb the brain because they are the same ones over and over,” he said. And thus the idea for his allegorical novel, The Emergency, was born.

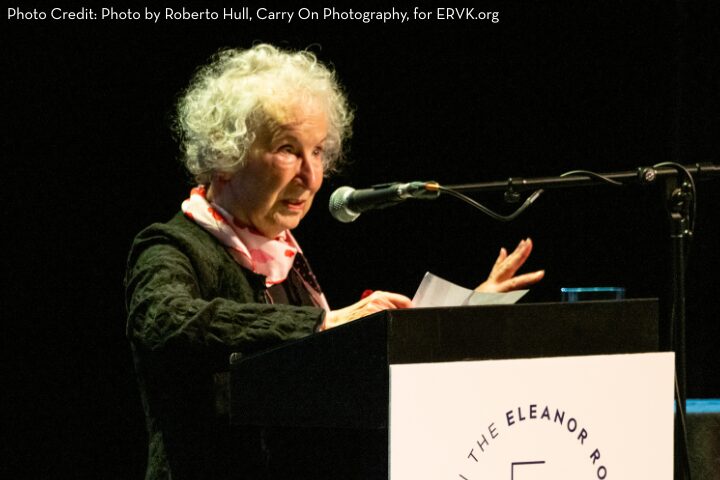

Packer joined fellow Atlantic writer Jennifer Senior in November at the Brooklyn Public Library for a lively discussion of the new release. Set in an unspecified place at an unspecified time, The Emergency traces youth rebellions that emerge in the wake of imperial collapse. The story is told through the perspectives of Dr. Hugo Rustin, his wife, and his daughter, who adopt contrasting outlooks on their own people, the urban Burghers, as well as the neighboring rural Yeomen. As the novel progresses, tensions run higher and higher both within the Rustin household and among the dueling groups that only recently comprised a cohesive empire.

Senior kicked off the night by introducing Packer as one of her writing idols. “It’s not just because he writes with a certain kind of intellectual dexterity or the ability to analyze things from 40,000 feet,” she said. “It is because he started as a novelist, and you can tell when you read him.”

Packer wrote two novels much earlier in his career — though he wasn’t a self-assured writer when he did, “and that’s why no one here has heard of them,” he joked. He’s now more confident in his ability to tell a story with tension and forward momentum, but returning to the novel form intimated him nevertheless.

He compared the experience to skiing after a long time away from the sport: “It’s like… ‘This is dangerous stuff, and I haven’t done it for a while, and I’m older. Maybe it’s not smart.’” But as Packer continued to write, a world of imaginative possibilities opened itself up to him, he said.

During the talk, Senior inquired about the familial tension foregrounded in the novel, especially the strained relationship between Rustin and his teenage daughter, Selva, who embraces the radical Burgher youth movement with open arms. “It goes so far beyond, ‘How do you get along with your Trump-loving uncle?’ which is the most that we see in mainstream stories,” Senior said.

Packer told the audience that the Rustin family unit fractures alongside the society they inhabit. “It’s under this pressure of one old world disappearing and a new one kind of struggling to be born, and there’s a huge generational divide opening up,” he said. “Rustin and Selva, throughout their journey in the countryside, are locked in this power struggle over who sees the world more clearly, who is able to adapt to this new world [better].”

Senior also asked Packer about one of the final scenes in the novel, in which the Yeomen invent a “shitapult” to attack the Burghers. She wanted to know whether Packer anticipated that the scene might be prophetic — President Donald Trump recently reposted an AI video of himself dumping feces on No Kings Protestors — and whether Packer predicted there would be any political violence in America’s future.

“I did not expect it to intuit the lower mind of the president, and I was kind of shocked and disturbed when it did,” Packer responded. “But the reason I invented this device was because I felt, ‘What is it that would bring us to the lowest point?’ … ‘What would take away the basic dignity of everyone who it touches?’ A shitapult — and that is, unfortunately, a feeling I have had more and more lately about the way our country’s moving.”

Quoting Abraham Lincoln, Packer said that if we continue to loosen our country’s bonds of affection, violence will become more likely. That possibility is the nightmare of the novel, he explained — though it’s not the last word in the book, which ends with a recognition of the characters’ shared humanity.

“This novel does not take a political position, but it does take a moral position, which is if we do not restore a sense of common humanity, we are going to be in deep, deep…,” Packer trailed off.

“Doo doo,” Senior said, finishing his sentence and concluding the talk.

Looking to read more about or purchase The Emergency? Check out our PEN Ten interview with George Packer, and buy the book here.