In a recent interview, the new PEN America president, Dinaw Mengestu, reflected on the organization’s role within a global network of writers standing against repression and censorship, and on the work of upholding a culture where every voice can be heard. For him, defending free expression can not be separated from the defense of imagination itself. He also shared the books that continue to influence him and the joy he finds in reading and rereading—acts that, in their quiet way, resist the forces of cynicism and erasure.

Mengestu was interviewed by Geraldine Baum, PEN America’s communications chief. The transcript was edited for brevity.

What inspires you about PEN America’s mission? And how will you use your voice and leadership to make a difference as president?

Long before I joined the board I obviously knew about PEN America, and I knew it was something that, as an aspiring writer, I wanted to be a part of. [It] had this great history of writers who I’d read and deeply admired coming together to help other writers who were being persecuted. And the idea of being part of that community was always profoundly appealing,

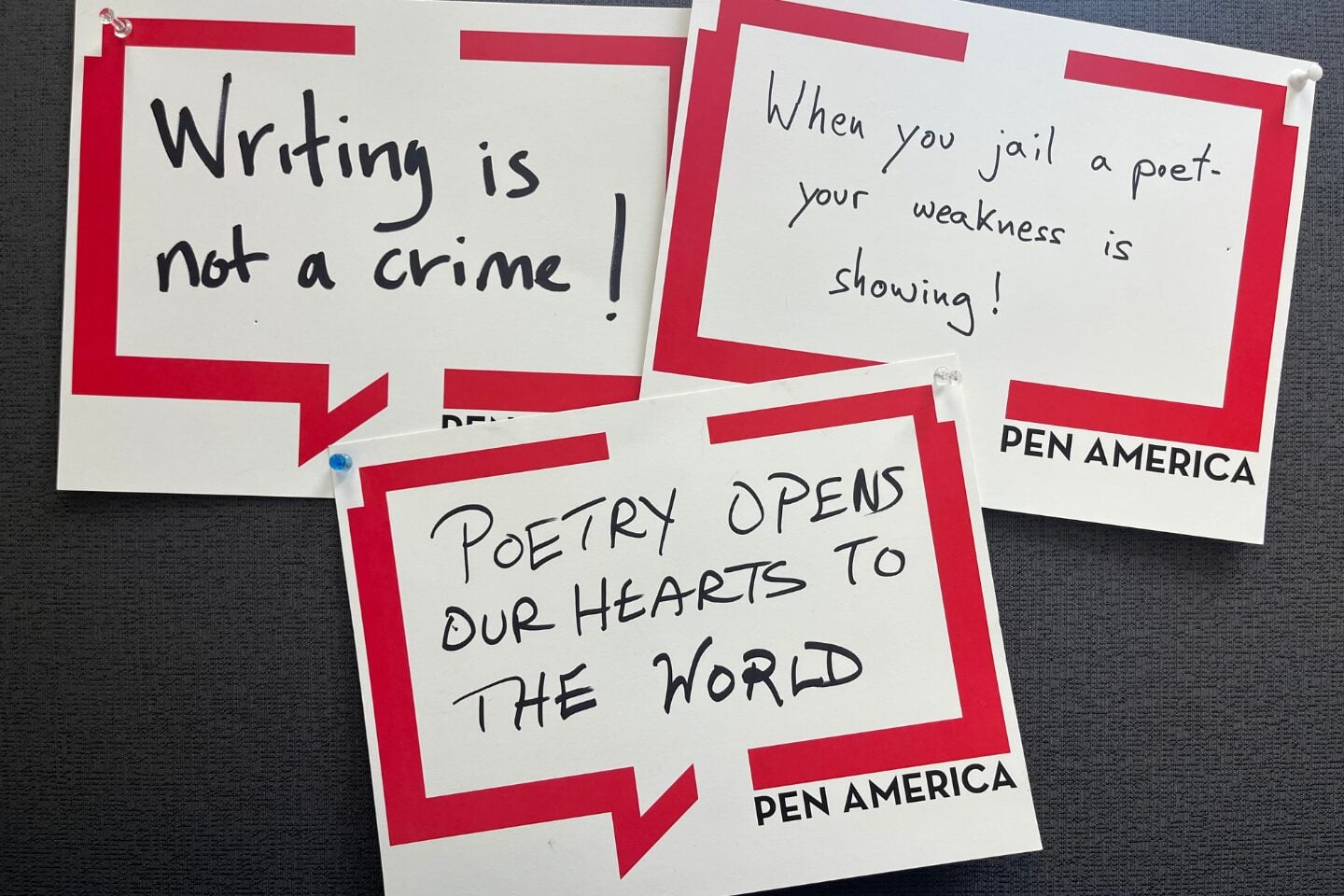

One of the first things I was considering was, what can we do to promote and spread the joy of literature, to bring literacy out into the world, and to make literature, to make reading, to make the conversations that reading inspires accessible to more people. But it’s also been joined by the very complicated political reality we live in right now, in which the threats to our free expression are numerous and growing. And when I think about what it means to spread and promote the value of literature, I have to consider all the threats that writers collectively are forced to endure in this moment.

And so what I hope to do is to find a way to bring these two together to advocate for literature and the value of literature and what it does for our communities and our own private lives, while at the same time also being a fierce advocate for free expression and showing people that without literature, we don’t actually have free expression, that we need the two together to understand what makes free expression so valuable and so important.

What is the greatest threat to free expression right now?

Out of all the many threats that we face when it comes to our free expression, certainly the most obvious one comes from our government. But it’s also a bit more nuanced than that as we think about all the ways in which our ability to say what we want to say, to express our ideas and our values are under threat, not necessarily because of a specific law, but because we know that there are subtle and sometimes insidious ways in which we might put ourselves at risk if we say what we think, if we express what we feel. And that’s particularly true for people who are advocating for a fundamental value, which is that all people are equal and deserve the same treatment and the same dignity. And if you are somebody who advocates and believes in that, particularly when it comes to certain communities – think of trans communities, the LGBTQ community, Palestinian lives– to advocate for those puts you at risk in a way that is quite distinct from anything we’ve experienced before. We can see that it’s not only the risk of being canceled, in whatever way that term might have been used, but, now actually detained and arrested.

How can we make our [advocacy] work as a force at this moment?

For people to understand why this matters so much, they need to be reminded why they took so much pleasure and so much joy in literature, in art and films, to begin with. And I think when you are given the opportunity to see and be reminded of that, you understand better what the stakes are, and you understand why what we do is so essential. More fundamentally, we are acknowledging that without books we are losing our culture. We are losing the kind of diversity of our culture, and we are faced with a large political and cultural force that is trying to define us in very singular and limited terms.

And PEN America’s work in literature, and in the defense of free expression, is also a defense of a culture that can only exist in a country like this, where we have such an incredible plurality and range of voices. And if we do not make room for those voices to be heard and celebrated, we run the risk of finding ourselves 10 to 20 years from now living in a world that is far more monolithic than the one we live in. And that plurality—that democratic possibility that we take for granted—begins to erode bit by bit.

I’m hearing you say that as we defend free speech, as we speak out, we have to explain more the value of what we’re speaking out for?

Yeah, I was thinking that we can find ourselves in a moment where you don’t need to arrest writers anymore, because what they do doesn’t matter. And that, to me, feels like the greatest threat. The long term threat and what we are facing right now, not only from political and state actors, but also from AI— is a world in which everything is fake, in which everything is controlled or created by a device or a machine. The idea of the importance of the singular voice begins to get diminished, which is already happening.

We’re part of this global network of PEN centers, and it’s at a moment when the United States is disengaging from the world. How can PEN America, as part of this global network, be an antidote to that?

I think the history of the PEN chapters has been a history of working together against repressive governments, and the power of this collective body is quite phenomenal. We also benefit enormously from being reminded of just how much is at stake in other countries when we look at writers and the risks they’re willing to take to defend their free expression, but also their culture and literary expression. I think we can not only learn from them, but also be humbled by that.

And of course, there’s the World Voices Festival, which brings people from all over the globe, hundreds of writers and it reminds people that we’re part of this international community, that these borders don’t exist when it comes to writers.

Certainly, when we bring a diverse range of authors from around the world to celebrate literature, to celebrate the complexity and diversity of our cultures, it serves as a kind of antidote to the current moment, but also reminds us what really matters most in the long run. And that this particular moment, as difficult as it might be, isn’t the end, and that we are able to still come together and in our convergence, raise a collective, powerful voice against that idea that we should be separated.

What do you draw from your literary work and experiences to build greater support for PEN America’s issues? I’m wondering if there’s something that you really want to do more at PEN America based on your experiences as a writer and as a person who’s seen America from a unique perspective.

I think we have seen through novels and books and plays and essays that there is a desire and a real need to see the full spectrum of our humanity displayed through art. And that display has been fantastic. At the same time we live in a moment where the threat isn’t Will anybody care? but knowing that behind every book ban, behind every threat to immigrants being able to speak out is a larger argument being made: that these stories shouldn’t be heard, that these experiences shouldn’t be talked about, they shouldn’t be written about, they shouldn’t be said. I think what writers are trying to actively do is not only push back against that for our own work but also because we know that that threatens the next generation of writers. It takes the power of those stories away from those future voices.

Now, fun questions. What book is on your nightstand right now?

I have a tendency to have many books on my nightstand at the same time, and so I’ve been in a process of rereading Disgrace [J.M. Coetzee], and Shadow King [Maaza Mengiste] at the same time.

Is there one book that holds really special meaning for you?

There are so many books that hold special meaning for me. If I had to choose one book I would probably say Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih.

And what are your reading habits, in terms of genre, subject, ideas? Do you have one genre you love, or one subject that you go to for relaxation?

Yeah, I always think of all reading as sort of joy and I read because I want to. I want to find myself sort of blown away by someone’s language and by someone’s understanding or perception of the world. I want to be taken into a perspective that I’ve never been in before. I read because I want to be reminded of just how great literature can be. So I find myself, particularly in moments like this, returning to books that I’ve read because [of] that joy, of entering back into a story that you know will endure. There’s something really fantastic to that.

Curious about what you think—what is the role of the writer right now?

I have a friend who’s a poet, and we were talking about the role of poetics and poetry in this moment, and she made really [a] brilliant idea, that the very act of thinking and willingness to write is already doing something important. Because we are under so much pressure not to want to do that kind of work, there’s so much more seeming value for our feelings, for our understanding of who and where we are in the world. So I don’t think the work itself needs to try to take on the world. The very fact that we are willing to make that space—and I mean this both for readers and writers—knowing that there’s so many other pressures asking us not to do that that there’s real value in that.