Late last year, officials at Texas’ seven public university systems began combing through the syllabi and course descriptions of thousands of classes offered at dozens of institutions, searching for hints that professors planned to discuss any aspect of race or gender identity.

As a result, stories of course cancellations, syllabus alterations, and prohibited readings continue to emerge from Texas public universities, the latest signals that academic freedom in the Lone Star state is in serious jeopardy.

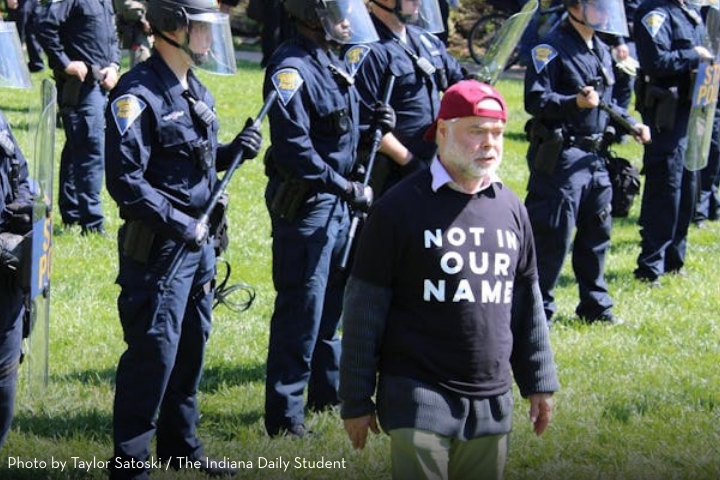

To learn more about the impact of these cuts on Texas campuses, PEN America is leading a delegation of writers to Texas A&M in response to these escalating violations of academic freedom, including the barring of Plato from a philosophy course and the elimination of a Women’s & Gender Studies program. Through private meetings and a public panel, the delegation will engage faculty, students, and administrators in conversation about academic freedom in Texas and beyond.

The curriculum audits – reportedly relying in part on artificial intelligence tools – began after SB 37, a new law prohibiting faculty senates from making final decisions on curriculum, took effect September 1. That law consolidates authority over academic and non-academic matters within each institution’s governing board and mandates regular reviews of general education curriculum.

Even though the first general education review is not due until 2027, boards of regents and administrators of Texas university systems have wasted no time in exercising the broad authority granted by the state legislature. Despite the fact that there are no state or federal laws regulating the topics a public university professor can teach, several university systems claimed reviews were being conducted to comply with applicable laws. Texas Tech University leaders have pointed specifically to President Trump’s executive order and a letter from Gov. Greg Abbott declaring there are only two sexes, along with Texas HB 229, which also took effect Sept. 1 and makes a similar declaration. The Texas state law does not, in fact, apply to university classrooms, nor does the plain text of the federal order. However, state officials and administrators are preemptively cracking down on speech beyond what the text requires and in violation of constitutional protections for academic freedom.

In the midst of these audits, two university systems, Texas A&M and Texas Tech, adopted or issued educational gag order policies revised as recently as December, that severely restrict classroom discussion of race and gender issues. Though both allow exemptions for a “necessary educational purpose,” that determination is made by the system president in Texas A&M’s case and, in Texas Tech’s case, by members of the System Board of Regents, rather than by the faculty with appropriate disciplinary expertise. Though other systems have not released policies that so overtly censor these topics, course cancellations statewide are following an unmistakable pattern as a wave of censorship engulfs academic institutions across the state.

Faculty at Texas A&M University learned as the semester was about to begin that roughly 200 courses in the College of Arts and Sciences could be affected by a new system policy restricting classroom discussions of race and gender. The implementation of this policy led to absurdities like administrators directing a philosophy professor to remove readings by Plato from a core curriculum course or be reassigned. (Professor Martin Peterson has since replaced the Plato readings with lectures on free speech and academic freedom.)

Other courses, including an introductory sociology course on race and ethnicity, and a graduate course in ethics that was already underway, were cancelled, while a communications course on religion and the arts was among the classes renumbered and stripped of core curriculum credit.

At Texas Tech, the newly imposed restrictions led a veteran professor to cancel plans to teach a course in the Communications Department rather than have her curriculum combed over, while others have taken steps like slapping “Censored” or “Do Not Read” on a syllabus next to certain pages of a required text.

At Texas State, faculty were initially left in the dark about what they might be required to remove from their classes, followed by guidance on how to use a “neutral tone” in curriculum. But they were given no sense of any process for appealing course content decisions handed down by the administration.

Chilling Effects Follow Viral Classroom Recording

This wave of scrutiny began in the wake of the September firing of Texas A&M Professor Melissa McCoul, after a student secretly recorded herself disrupting a lesson in a children’s literature class. The student accuses McCoul of breaking a federal law that requires professors to teach that there are only two genders (there is no such law) and insisting that exposing her to the idea of gender diversity violates her religious freedom. The student was asked to leave, and a short clip of the video posted on social media by State Rep. Brian Harrison went viral. After Gov. Abbott stated on X that he wanted the professor gone, McCoul was summarily fired without the required pre-dismissal notice, opportunity to respond, or hearing.

Two administrators in McCoul’s department were also demoted, and Texas A&M President Mark Welsh, who initially defended McCoul on academic freedom grounds and was also secretly recorded by the student, was forced to step down as president a few days later despite firing McCoul after political pressure.

The American Association of University Professors’ Texas A&M chapter said that McCoul’s dismissal “appears to have been implemented in direct response to pressure from Texas political leaders and the governor,” and warned that the action “sends a chilling message to the entire academic community in Texas.”

McCoul in early February sued the university and administrators, claiming that they knowingly violated her free speech and due process rights in order to meet Abbott’s demand for her firing.

As so often happens with fear-induced censorship crusades, across Texas higher education it doesn’t so much matter anymore what started it; the effects are turning up everywhere. Faculty are cancelling classes, or stepping away from teaching. Beyond the classroom, there was even the cancellation of a planned visit by the Black History 101 Mobile Museum at Texas State University, apparently to comply with the state’s anti-DEI law.

Kelli Cargile Cook, a professor emeritus who founded Texas Tech’s Department of Professional Communication, told the Texas Tribune that restrictions imposed in December in a memo from the system’s chancellor on how faculty discuss race, sex, gender identity and sexual orientation in the classroom, combined with the new course content approval process and a threat of disciplinary action against faculty who don’t comply, led her to cancel a class she planned to teach during spring semester and instead draft a resignation letter.

“I can’t stomach what’s going on at Texas Tech,” said the veteran educator. “I think the memo is cunning in that the beliefs that it lists are at face value, something you could agree with. But when you think about how this would be put into practice, where a Board of Regents approves a curriculum — people who are politically appointed, not educated, not researchers — that move is a slippery slope.”

For Professor Leonard Bright, a public policy professor at Texas A&M, the curriculum reviews led to a request from the dean of the Bush School of Government and Public Service asking him to share when and how his graduate class Ethics in Public Policy would address race, gender or sexuality. In a letter to faculty and students announcing the cancellation of the class – and shared publicly before Bright was informed of that decision – the dean claimed Bright “declined” to say.

Bright, however, claimed that in an email to the dean, he wrote that “issues of race, gender, and sexuality are not peripheral but integral” to the class, which focuses on ethics in public administration practice and how it is shaped by public servants and the people they serve.

“I tried to underline that throughout the course—in every reading and every case study they have, in current events, in book reviews—[race and gender] will be central to this class. I guess [the dean] didn’t like that,” Bright told Inside Higher Ed. “It appears to me that he wanted me to say, ‘I’m just discussing it here,’ so they can limit or censor this and say that they’re only approving me to discuss it on this day or that day. I thought that that was inappropriate. I could not teach that class under that kind of condition.”

Bright posted a copy of the dean’s email on social media with a note criticizing the process. “The message was clear: Be very afraid no one can save you from being censored at Texas A&M.”

Expanding the Web of Control

As PEN America wrote in our recent report on academic censorship, 2025 saw political efforts at expanding a web of control over higher education unfold in multiple directions across the country. Texas is a prime example, but these curriculum audits are not happening in isolation from other state and national trends. The report found that more than half of U.S. college and university students now study in a state with at least one law or policy restricting what can be taught, or how campuses can operate.

One recurring tactic used to restrict what is taught is stripping faculty from any significant role in campus governance.

Texas last year abolished faculty senates as part of the sweeping educational reform law, SB 37, removing the voices of those who teach from decision making. Reconvened faculty senates now have only advisory roles.

A member of the Texas State Employees Union, writing anonymously for fear of retaliation, told the campus newspaper last semester there was a link between the decline of academic freedom on state campuses and SB 37.

“What’s happening with the current course audit at Texas State shows the troubling erosion of shared governance as a result of Senate Bill 37 from the 2025 legislative session,” the TSEU member wrote to the University Star. “Myself and other TSEU members spent hours and hours at the Capitol listening to and giving public testimony against SB 37 during the session because we knew exactly how bad it would be. And now we’re seeing it play out on our own campus.”

The union member wrote that the process for course revisions was unclear, with professors left to wonder if proposed changes would be approved or denied by administrators. “Will it be a simple yes or no? Will there be any room for conversation or negotiation?” the TSEU member wrote. “Either way, it signals a shift toward centralized, top-down, ideologically motivated control over academic content stemming from the Governor’s office and his appointed Board of Regents who have final say over curriculum.”

Adding insult to injury, the state also wants students to play a part in enforcing its efforts to remove what it considers taboo topics from classrooms. A website created in January contains forms designed for complaints about alleged violations of SB 37 and another law, SB 17 (2023), which banned nonacademic diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in Texas public higher education.

The result of all these developments is painstakingly clear: that freedom of thought and the freedom to teach and learn may soon be a memory in Texas universities.