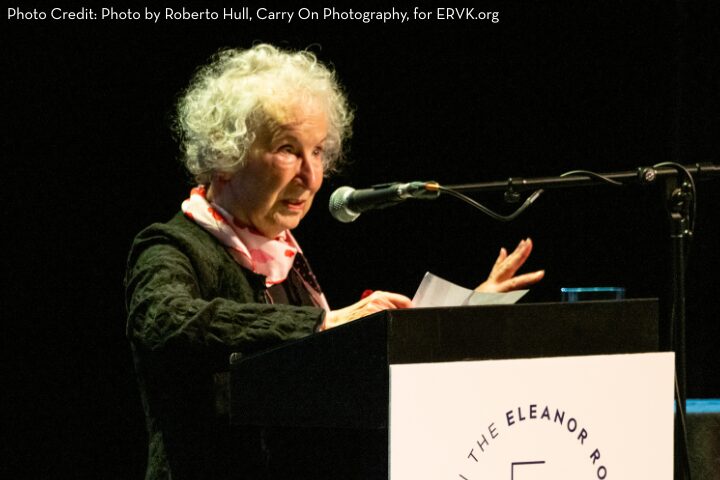

Amid the alarming surge in book bans across the United States, award-winning and New York Times bestselling author Malinda Lo has become an ardent champion of the right to read. Last month, her advocacy earned her the 2025 Eleanor Roosevelt Center Bravery in Literature award, co-presented by PEN America. As Lo stated in her acceptance speech, free expression has always been a personal issue for her because her family immigrated from China, the world’s leading jailer of public intellectuals, so that they could speak without fear of punishment.

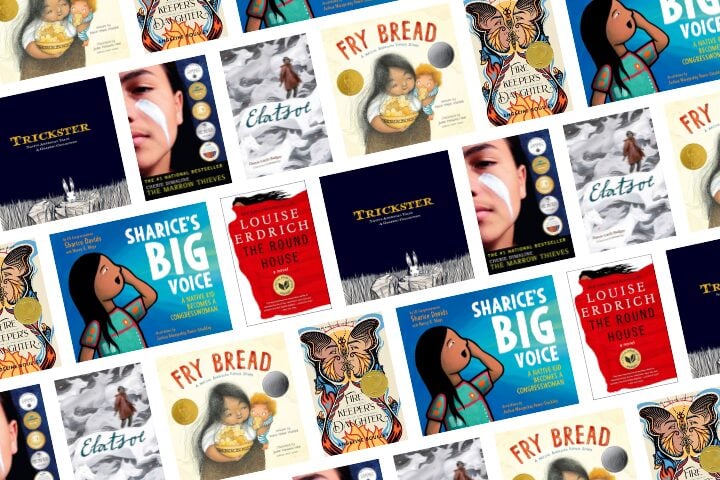

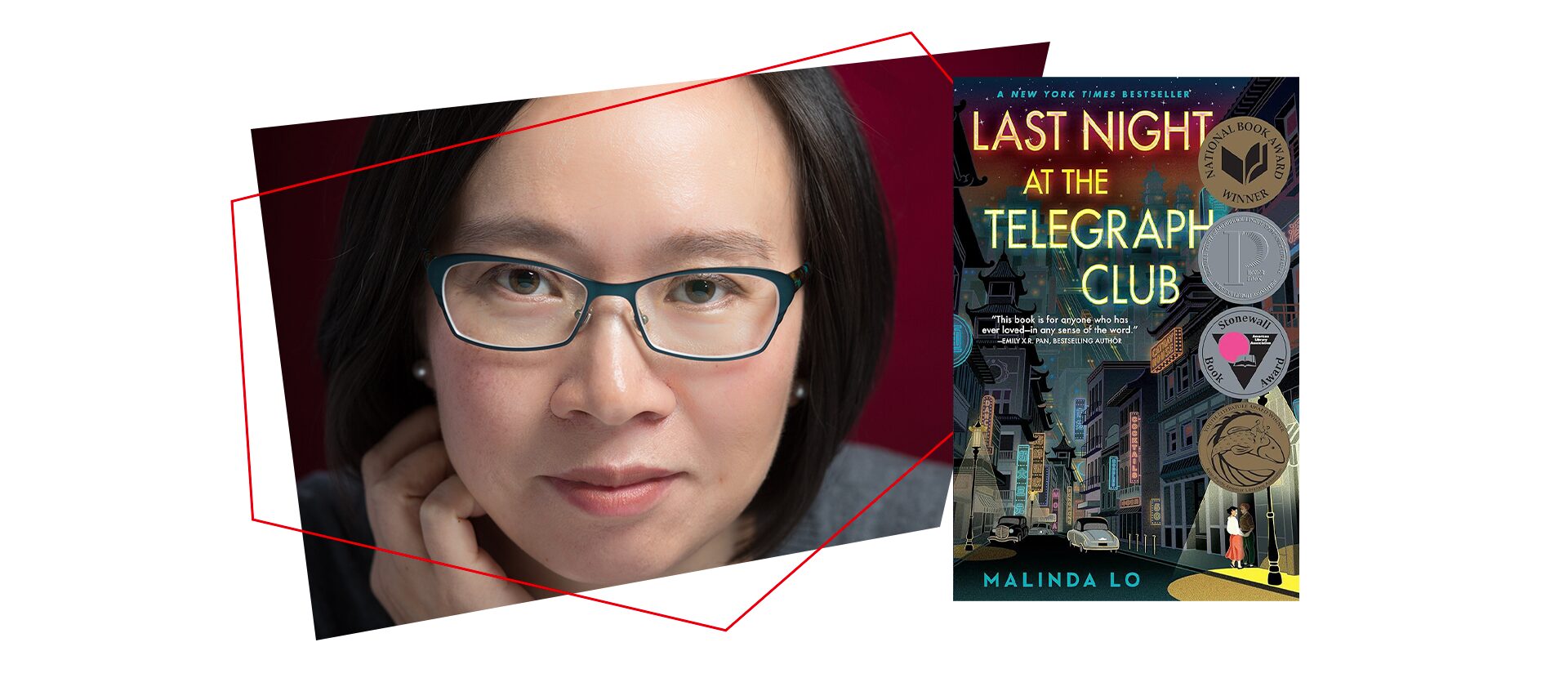

But it’s personal for a second reason, too: Lo’s books are among the most targeted in the country. Last Night at the Telegraph Club, winner of the National Book Award and the Stonewall Book Award, ranked fourth on PEN America’s most banned books list for the 2024–2025 school year.

The book, which follows a 17-year-old Chinese American girl in 1950s San Francisco as she begins to explore her sexual identity, also racked up 35 bans the year prior. Since 2021, three of Lo’s young adult books — A Scatter of Light, A Line in the Dark, and Ash — have been hit with bans as well, according to PEN America’s banned books indexes. Like Last Night at the Telegraph Club, they depict queer romances.

For the second installment of our interview series about the role sex plays in young adult literature, Lo explains her motivations for including sexual content in her novels. She also discusses pro-censorship groups’ pernicious tendency to pluck that content from its context, misconstruing its meaning in service of their own agenda.

Read the first installment of the series, in which Executive Editor at Penguin Random House’s Dutton Books for Young Readers — and Lo’s editor — Andrew Karre debunks the myth that YA literature could ever be sex-free, here.

Lo’s young adult novels don’t have an agenda, sex-related or otherwise.

Groups restricting books — and even English teachers at times — take for granted that Lo writes novels to teach young readers lessons. And while it’s certainly possible to analyze her books and teach them in a classroom setting, Lo never sets out to make them didactic. “That’s not the point of writing for me,” she said.

Instead, Lo’s books are a way for her to investigate complex questions that pique her interest. Across her seven young adult novels, the majority of the questions she’s explored concern different aspects of identity, including race, gender, sexuality, and personal interests. “All of those things go into identity, and one is not necessarily more important than the other.”

“If sexuality is a part of [a character’s] journey and part of the story, then of course I’m going to write about it,” Lo continued. “That’s why there is sexuality in my books: because it is part of life. There’s no nefarious purpose.”

Sexual content, from Lo’s perspective, is not qualitatively different from any other content contained in her books; it’s just one of many avenues through which she “tries to explore what it means to be human.” Even the process of drafting scenes that contain sexual content differs very little from drafting seemingly more quotidian scenes, like a character’s trip to the grocery store, she said. Whatever the plot, Lo uses the same questions to guide her writing: What are her characters thinking and feeling in that moment? What are the motivations behind their speech and actions?

Even when it’s not didactic, young adult fiction can implicitly affirm different identities.

“The interesting thing about writing and being a writer is that I get to, through books, make different readers feel things,” Lo said. “It’s very magical.”

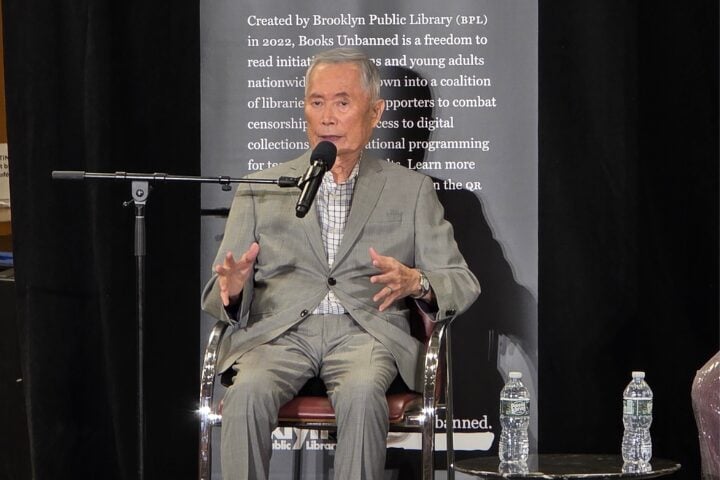

In her perspective, the power of literature rests in its unparalleled capacity to provide entry into the minds of complete strangers. “It can give you information about people who are different from you — and I think that book banners don’t like that,” she said.

“If you’re an anti-gay conservative,” she continued, “you do not want your 16-year-old daughter to read my books, because that girl is going to understand that queer girls exist and that it’s okay to be gay. … You definitely do not want the magic of reading to get to your teenager.”

Stripping sexual content of its context is a surefire way to fail authors and readers alike.

Lo said that all too frequently, groups that promote book bans share short excerpts from YA novels that narrate or mention sex, sparking confusion, outrage, and fear.

Time and time again, they’ve isolated a scene from Last Night at the Telegraph Club where the protagonist, Lily, stumbles upon some lesbian pulp fiction (“which is supposed to be very sexy,” Lo said). The scene allows readers to follow along with Lily as she encounters something unfamiliar yet enticing and attempts to make sense of it.

But detached from the rest of the book, it becomes impossible to understand the significance of the pulp fiction — just as it would be to understand the import of any portion of the book devoid of context. Take, for example, the moment Lily comes upon an extremely racist mechanical diorama of Chinese opium smokers in an amusement park. On its own, the description of the diorama would strike readers as disturbing and hateful; in the book, however, it’s Lily’s thoughtful reaction to the diorama, rather than the diorama itself, that Lo foregrounds. “When you read the book and experience it through her eyes, you understand her perspective and why that scene is in the book,” Lo said.

Once, an English teacher informed Lo that individuals promoting book bans were sharing cherry-picked excerpts of one of her novels and asked which excerpts Lo might show them to refute their argument. “I was like, ‘The whole book! You need to read the whole book!’” Lo responded.

In order to fight back against book bans, advocates need to become more comfortable talking about sex.

“Book banners actually kind of like to talk about sex,” Lo said. “They like to talk about how bad it is and how much we should not be having it … or writing about it or thinking about it, ever.”

On the other hand, Lo noted, advocates against censorship are not always equipped to have conversations about sex.

Lo previously wrote for queer publications in San Francisco, where sex was a normalized and frequent topic of discussion — but in New England, where she lives now, it’s an entirely different story, she said. “People are afraid to talk about sex,” she said. “When you’re in a public space with a mixed group of people, people are squeamish. And I know it’s because they’re afraid of offending someone, they’re afraid of being seen a certain way — they’re just afraid, for many reasons.”

If advocates want to stand up for young adult books successfully, she said, it’s time for them to learn about how to discuss sex with clarity and confidence.