In China, Winnie the Pooh is not just a sensitive topic, but a censored figure due to an apparent likeness it shares with the country’s president, Xi Jinping. In Russia, as authoritarianism grasped a stronghold over the country, a certain type of laughter became recognizable—the nervous kind. Jokes about being searched by the riot police and about hiding phones in cat litter became a way to predict and prepare for worst-case scenarios as a coping mechanism.

Now that she is in the United States, where 350+ words have been scrubbed from government websites by the Trump administration, journalist Anna Nemzer hears the same sounds.

“I just feel such a horrible déjà vu, because I recognize this laughter, and I understand that it’s a very common and very obvious defense reaction,” said Nemzer, journalist, co-founder of the Russian Independent Media Archive (RIMA).

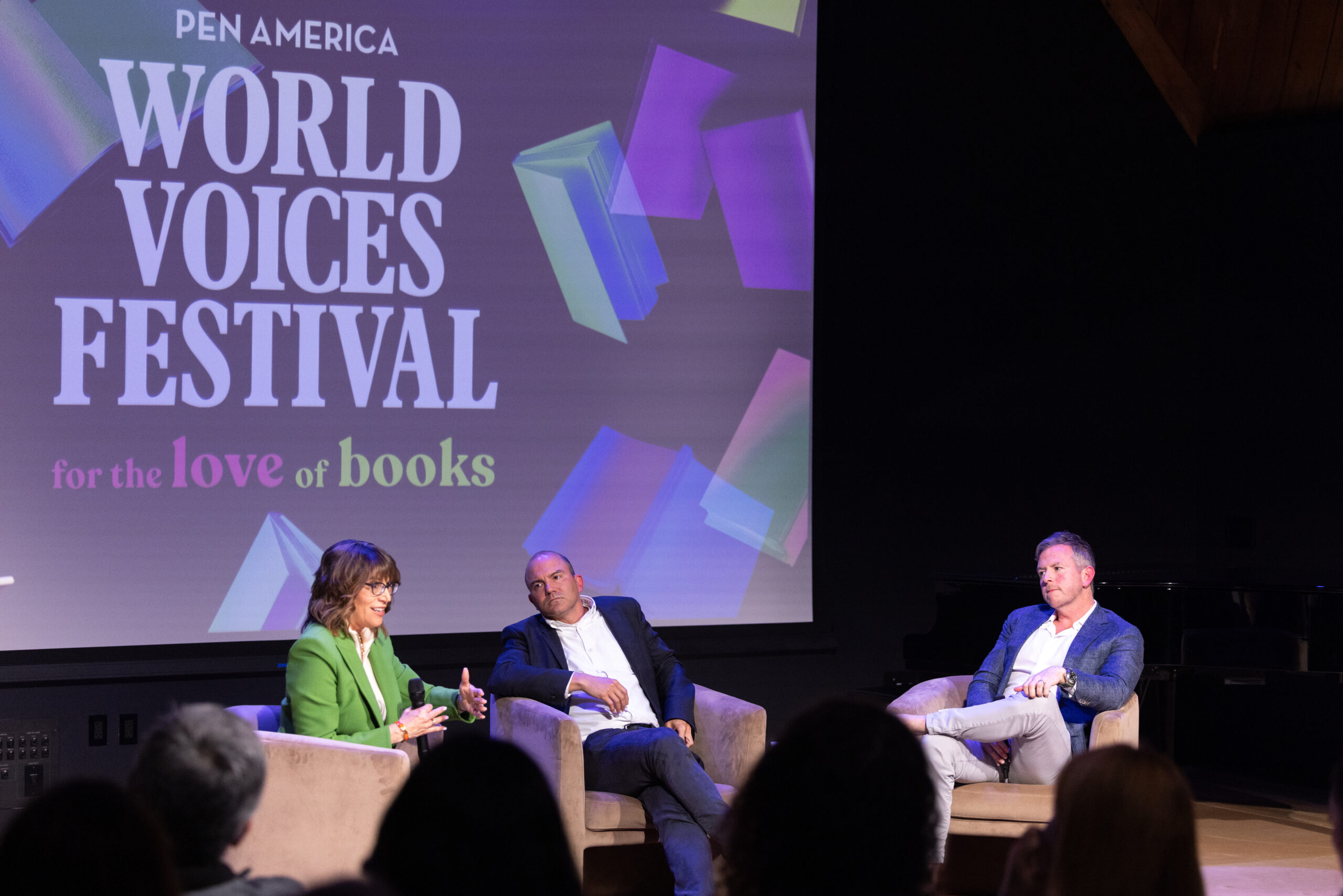

She was speaking at the 2025 World Voices Festival panel, Erased: Media Erasure and Authoritarianism, and was joined on stage by M. Gessen (Surviving Autocracy), journalist and New York Times opinion columnist, and Yaqiu Wang, human rights and democracy researcher and advocate. Moderated by Viktorya Vilk, Director, Digital Safety and Free Expression at PEN America, the discussion delved into the nuances of how media is one of the first to fall victim under authoritarianism, and what America should watch out for.

From the playbook of autocrats, for aspiring autocrats

Pressuring the media, erasing content off of the internet, and disappearing groups of people who identify themselves a certain way are all pages out of the authoritarian playbook–symptoms before the sickness really sets in. And for journalists and researchers who have experienced it first-hand or have spent decades tracking these tendencies in other countries like Russia and China, the patterns are all too familiar.

M Gessen: “We used to joke in the Soviet Union that Russia is a country with an unpredictable past. If you want to control the future and if you want to control the present, you have to control the past. Autocrats and aspiring autocrats exert pressure on the media because they want their message transmitted. They don’t want counter messages. They tend to attack the past at the same time that they’re attacking the present. It’s a complete cacophony. It’s at once an effort to create an imaginary past that fits the autocrat’s agenda and an effort to deprive people of those tools of self understanding by attacking language, media, and the historical record.”

Anna Nemzer: “It’s obvious that any dictatorship has a special need to make people feel isolated, to make people feel totally alone. Gathering around anything or anyone doesn’t let them do so and so they have to make a lot of actions to make sure people feel really isolated. The [Russian Independent Media Archive] itself might be also this point of resistance, of gathering people together, of collecting….Because knowledge about the past and memory about the past is some kind of support system, and that is what they’re also trying to erase and to demolish.”

Yaqiu Wang: “The thing that people fear in Russia or in America, it’s already a reality in China. Dystopia is already a reality. It’s because the Chinese government has now over 17 years experience of doing it, and they are very good, their tech is superior. When the internet entered China, they already were building the infrastructure of censorship.”

Confiscating the tools for understanding the self

When all that is fed to a population is propaganda and manufactured information, people are easily bored. So distraction is the next step.

Wang: “There’s censorship and then there’s propaganda. The third aspect I really want people in the West to know is that there’s really entertainment—very interesting videos and jokes that are devoid of politics really fuel the information space, and people have something to watch, something to enjoy. You don’t realize the stuff that is being censored.”

Gessen: “There’s no difference between journalism and history books and plays and music. All of these are ways to understand yourself and to understand your society and to understand politics. So if you’re robbed of those things, you’re robbed of the ability to form opinions, which is what totalitarian regimes want from you. The other thing that they also want from you is they want to isolate you. They want to create a particular kind of loneliness, and that means erasing any possibility of any affinity that’s independent of the state, whether it’s language affinity, cultural affinity, unless the state is feeding it to you, you don’t have the right to access it.”

Nemzer: “We knew that we didn’t have any institutions [in the Soviet Union]. We didn’t have any judicial system. The only institutions we had were the communities of people, the journalistic community, the independent journalistic community, the community of human rights activists, and so on. Some people that had to play this role had to take this responsibility of being an institution.”

The cost of keeping freedom alive

Refusing to be erased demands an active enlistment and commitment to being brave in everyday life, in our work, and our relationships.

Gessen: “I think people have to be at least a little bit brave. A lot of us have opportunities in daily life to make those choices. Those are some of the hardest choices to make. They’re much harder to make than whether you go to a protest, because, for most of us, it does not require a lot of bravery to go to a large protest in New York City, but these are the things that make a difference.”

Wang: “I just can’t emphasize enough to be braver than you think you can. In order to stand up, the only thing you lose right now is your job. Probably your nice house. But this is the least price you have to pay, because if you don’t pay the middle price now, you’re gonna pay a huge price. People go to jail, people disappear, people die for the right to speak, now you only need to lose your job.”

Nemzer: “People were giving this advice that maybe for this moment, we should lay low and just wait till everything is demolished. Dealing with this situation, which is totally unpredictable, it’s a very special challenge. And I honestly don’t think that just waiting might help. I’m afraid it’s quite a dangerous strategy. There are a lot of similarities, but at the same time, the situations are totally different.”