Jennifer Finney Boylan | PEN America President and Chairwoman

Jennifer Finney Boylan has been elected president and chairwoman of the PEN America Board of Trustees. Boylan, the author of 18 books and an English professor at Barnard College (where she is the Anna Quindlen writer-in-residence), points to the power of storytelling as her inspiration in joining the board in 2018. “My life has been changed by the books that I’ve read. And I saw how stories about people like me were able to change people’s hearts and minds.”

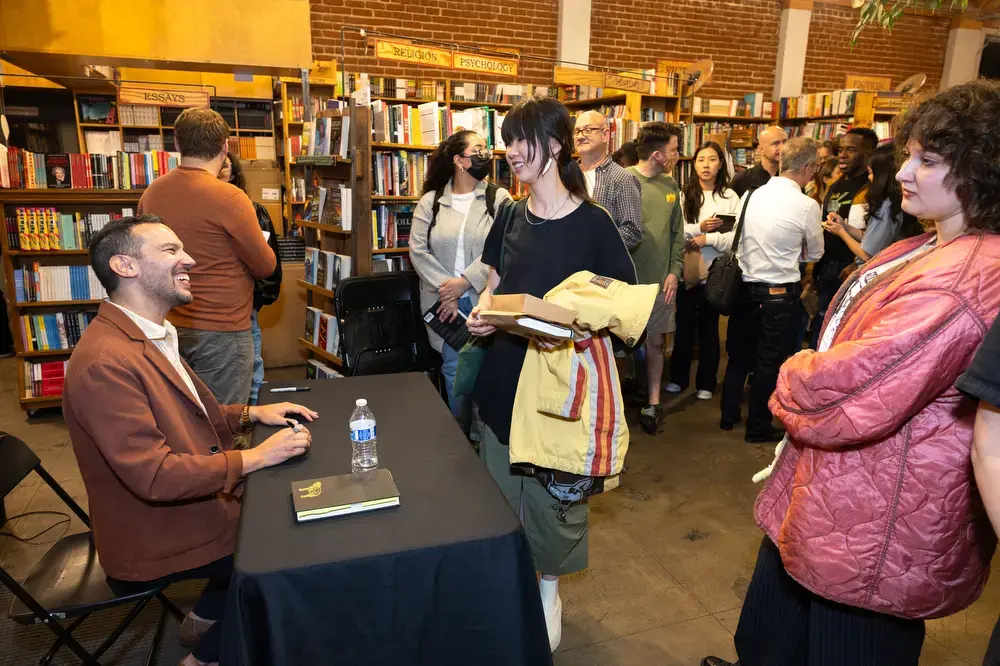

Along with novels and young adult fiction, Boylan has written two bestselling memoirs focused on her life as a trans woman. Most recently, she co-authored a novel, Mad Honey, with Jodi Picoult. Boylan follows a roster of notable writers as PEN America’s president including Salman Rushdie and Jennifer Egan, and most recently Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and screenwriter Ayad Akhtar, whom she succeeds.

She spoke to PEN America’s Suzanne Trimel, senior communications advisor, about why she became involved with PEN America, why she was drawn to its mission to defend free expression, and what she hopes to accomplish over the next three years of her term.

1. What accomplishments by PEN America make you the most proud?

Our defense and advocacy of imprisoned writers around the world. This year our Freedom to Write award was given to (Iranian human rights advocate and author) Narges Mohammadi and it fell to me to make the presentation of that award to her husband and family members [at PEN America’s gala last spring in New York]. Four months later she won the Nobel Peace Prize. Over the years, of the people who we have given that award to, most of them (46 of 52 awardees since 1987) have been freed, in no small measure because of the pressure and advocacy brought by PEN, along with others, of course, advocates and diplomats around the world. Being put in a spotlight like that is a way of fighting for people whose lives are in danger. I think of the Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich behind bars in Russia. And for what? For reporting the news. But there are more than 311 writers around the world who are imprisoned today for their writing. I’m proud of this work, although I am not proud that we live in a world in which that work is necessary.

I’m also proud of our World Voices Festival, founded by Salman Rushdie in the wake of 9-11 in order to bring writers from around the world to New York and stop being so myopic about the writers we read and the writers we care about. It’s a way of making writers – non Western writers– part of our literary community and helping readers and writers here to see them that way.

2. Why did you first get involved with PEN America?

I came to PEN for very personal reasons. I found that as I tried to explain to people what it meant to be transgender, it was very hard for people to understand the thing that I’d been feeling, to feel the world with the heart that I have. So you can show people the science behind being trans, you can show people the neurology. But none of that opens minds as quickly as reading stories. Stories open a door. I think that in some ways the most important thing to understand about each other’s humanity is imagination. And if you want to open a door to the imagination, nothing does it as efficiently as a poem, as a play, as a book.

When I was a child growing up in a largely white suburb of Philadelphia, I knew that racism is bad. But when I read To Kill a Mockingbird in 1965, that gave me a very different understanding and experience of what racism means. The same was true later when I read Toni Morrison, when I read Larry Kramer. My life is changed by the books that I’ve read. And I saw how stories of people like me were able to change people’s hearts and minds. With this last book Mad Honey, almost every day I get a letter from someone who says “You know I believe in equality but I never got the trans thing. I didn’t even know what questions to ask before I read this book.” Stories change people and they change culture.

“Stories open a door. I think that in some ways the most important thing to understand about each other’s humanity is imagination. And if you want to open a door to the imagination, nothing does it as efficiently as a poem, as a play, as a book.“

3. How does storytelling motivate your involvement in PEN America’s mission of free expression?

This very business [of storytelling] changed my life. I have heard from people–and this is immodest to say— that their lives were saved by reading books I’ve written. When I stood on a cliff in Nova Scotia in 1988 summoning the courage to jump, I didn’t have any books by people like me to read. If there aren’t stories about you, there’s a way that you feel you don’t exist, that you’re invisible. The difference between now and then is that there are lots of books about people like me. It’s not about trans people— and I don’t want people to think that PEN is now going to be all exclusively focused on trans— it’s about allowing people to know that they are worthy of stories, that their lives have value, that there is a story for all of us. It’s narrative that connects who we are to who we will become. It’s storytelling. And when we talk about “difference” we’re most often talking about an issue that has come into public view, but what gets lost is that no human being is an issue. We’re talking about humanity.

4. What is the most important issue that you want to tackle?

Over the course of its history, there were times when PEN did not fight for all authors, when it mostly fought for white authors, for male authors, and fortunately that changed over time. PEN is doing a better job now of including LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) writers but until I joined the board, there had never been an openly trans author. I did not know whether there would be room for writers like me and whether writers like me were worth defending.

There is nothing as powerful in this world as a poem. There’s nothing as powerful as a play. There’s nothing as powerful as a book, and that’s why there are so many individuals in this country who are looking to ban books about people with lives like me, and especially about people of color. The way we can lose this war is by having our stories erased. I’m most passionate about having these stories heard, told, and published because that is the way to change the culture.

“It’s about allowing people to know that they are worthy of stories, that their lives have value, that there is a story for all of us.“

5. What did you think when you first heard that this movement to ban books was specifically targeting stories about LGBTQ people and writings by queer authors?

The books most likely to be banned are about queer experiences and about people of color and that should tell you whose stories they feel are going to change the world. And that’s what they fear; they’re afraid that these stories are going to change people’s hearts and minds and in a way, they should be afraid, because they are going to change hearts and minds. That is what books accomplish: they help us see the world through the eyes of someone else. Shining a light into the truth of the lives of all Americans is something we should be in the business of doing. How did I feel about this? It made me angry. I think some authors view being banned as a badge of honor. I wouldn’t view it that way.

6. How do you view free expression and why it is core to human rights?

PEN fights for artists and writers and the freedom to write and create. We are involved in the most important work in the world, fighting for free expression. In this country, there is nothing more important than the freedom to read. Free people should be able to read books. Free people should be able to write and publish. The freedom to read and the freedom to write are at the heart of the human experience. So in a crucial way we are defending humanity.

7. What are the obstacles that challenge progress on free expression and free speech issues such as the banning of books, the censorship of topics in public school classrooms?

I am not a First Amendment attorney, but we can all see there are a lot of bad actors out there who want to avoid responsibility for the things that come out of their mouth. What’s difficult now is that the difference between protected speech and hate speech is not exactly clear. It goes to something more complex than that old cliche about no one has the right to yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater. There is no easy answer and we are going to have to figure it out day by day, case by case. We’re seeing it play out now on campuses. If someone comes to campus with the idea to give a speech that someone like Jenny Boylan has no right to exist, well, maybe that’s hate speech, and I can assure you there will be people who will push back against that. My heart is with those students. I don’t want to be defending the speech of someone who wants to hurt me. But to some degree, that is the job. No one has ever had their opinion changed by someone telling them to shut up. But those who use free speech to advocate for repression, those people are often the more powerful. Not everyone has the same access to the same megaphone. So a lot of people use free expression as a way to stay in power and to punch down on those with a lot less power. I want to defend the right of people with whom I disagree to speak, but often they are the most powerful people. It’s complicated. Free speech is not a level playing field.

Read and listen to a 2020 interview and PEN POD podcast by Boylan about her writing.

Listen to a podcast from the Aspen Ideas Festival where Boylan spoke about being trans.