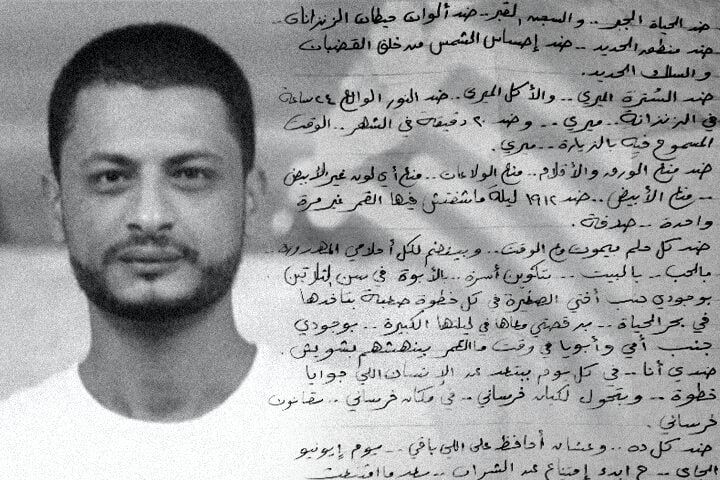

Abdelfattah Galal wants the world to know this about his son Galal El-Behairy: “Galal is simply a talented writer and a poet… Galal’s mode of opposition is his poetry.” El-Behairy, who received this year’s PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, was arrested for his poetry and song lyrics in 2018.

Friday, June 27 marked El-Behairy’s 35th birthday, his seventh spent behind bars, alone and separated from his loved ones. During a birthday gathering organized by the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center with his family and fellow Egyptian writers, Abdelfattah Galal urged the international community to stand in solidarity with his son.

Since his son’s arrest, El-Behairy’s father said, “Our lives have turned into numbness.” He added that, “The thing that gives me most hope and happiness is just the thought of his release, safe and sound… Everyone must stand with Galal, support freedom of opinion and expression, and uphold human rights.”

Under the leadership of President Abdelfattah El-Sisi, who came to power in 2014 after leading a coup d’etat the year prior, the Egyptian government’s widespread use of prolonged, pretrial detention against critics has silenced independent voices in an already limited space for free expression. Speaking at the event, PEN International’s Head of Middle East and North Africa Mina Thabet said, “Since President Sisi grabbed power, we are seeing a concerted effort from his side to make sure there are no other narratives.”

“One of the victims of this climate has been Galal,” Thabet continued. “He faced a military trial just for writing a poetry collection.” During the conversation, Thabet outlined how the authorities’ application of bogus charges and violations of fair trial standards have weaponized the legal system to stifle the expression of dissidents, journalists, and writers like El-Behairy. Egypt ranks among the top 10 jailers of writers worldwide.

The Egyptian authorities have unjustly jailed El-Behairy since his arrest in 2018—bringing new charges against him even after he completed a three-year prison sentence—effectively keeping him in detention indefinitely.

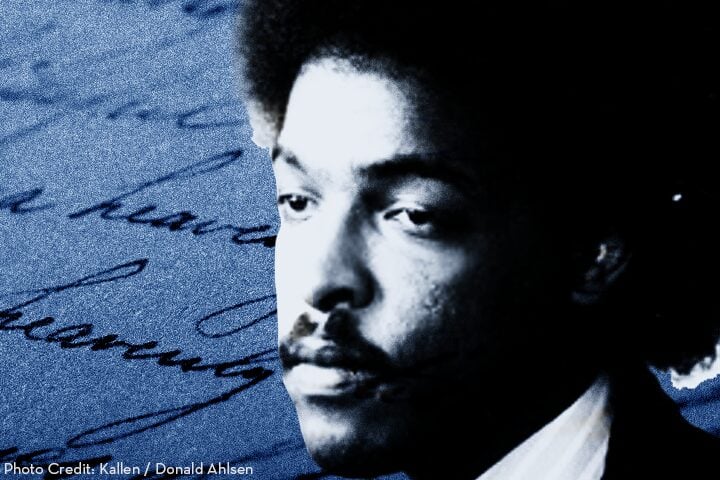

“We are living in dangerous times where oppression goes beyond politics,” said novelist Ahmed Naji, who was formerly imprisoned for 10 months in Egypt for his novel Using Life and honored with the 2016 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award. “It’s a time where the tyranny and fascist spectre looming over the world is not only about controlling politics and resources, but it’s about, now, strangling imagination and controlling how we feel and think.” Now living in exile, Naji chronicled his time in prison in his 2023 memoir Rotten Evidence.

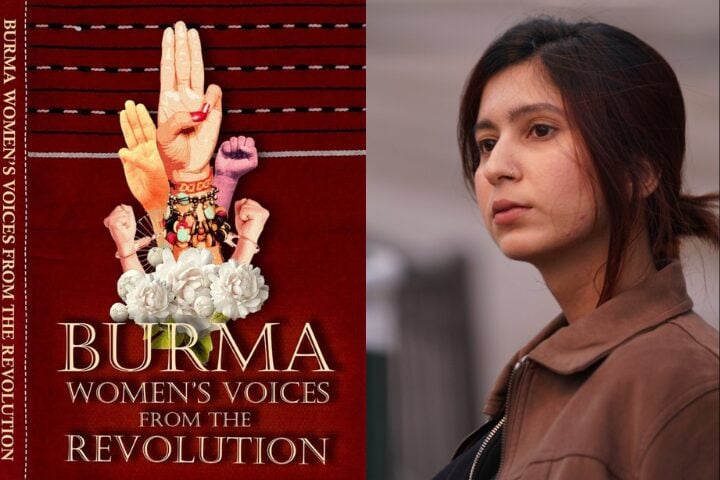

For some writers and journalists, the spectre of retaliation follows them and their work even in exile. Journalist and human rights defender Basma Mostafa was arrested multiple times in Egypt for her journalism until she ultimately fled the country. “Exile was the only way for me to survive,” Mostafa said during the discussion. She moved to multiple countries—Lebanon, Kenya, Germany, and Switzerland—but continued to face attacks in reprisal for her work. “Quickly I started to realize that exile does not mean safety for me, for a lot of journalists.”

In Germany, Mostafa was beaten in front of a government building in July 2022 during President Sisi’s visit to Berlin for a conference, which she had tried to cover as a journalist but was denied access. As she spoke critically about President Sisi to the crowd outside, two people surrounded her and physically assaulted her. “Everything after that day escalated,” she said. Mostafa has faced a multitude of other threats including doxxing, surveillance, and online gender-based violence across multiple countries. The Berlin-based Democracy Support Foundation e.V., which Mostafa co-founded, has tracked this trend in reprisals. Despite these threats, she maintained that continuing to write is “a tool to reclaim our power.”

Amid these ongoing threats to free expression, PEN International’s Thabet discussed the current, heightened crackdown on speech in Egypt targeting support for human rights of Palestinians. Egyptian authorities have punished protests and blocked independent news outlet Mada Masr for their reporting on the war in Gaza.

He noted that while the scope of repression is wider in Egypt, there are similar crackdowns in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe. “If you are imprisoning people and making an example out of them,” Thabet said, “you are spreading this climate of fear in society in which journalists, creatives, actors, artists, poets, writers become afraid of expressing their mind.”

Gathering and advocating for El-Behairy and other writers unjustly jailed for their speech is a double-act of solidarity—ensuring that these writers are not forgotten, while reminding those who speak out of our humanity. “We choose to be here, to stand next to poetry, and art, and creation and freedom of expression,” novelist Naji said. “If you have something different inside of you, don’t lose it, don’t suppress it. Feed it by reading poetry, by participating in such campaigns and solidarity.”

Naji strongly believes El-Behairy is still writing, no matter his circumstances in detention, because, he said, “for poets, you can’t stop poetry.” Closing the conversation with El-Behairy’s words, Abdelfattah Galal read a poem by his son, written from jail in 2023.

Convicted without conviction,

accused without accusation.

They planted all the noble principles in our hearts when we were young –

then they burned them,

and burned us.

They stomped on them,

and stomped on us when we were adults.

So we became afraid to our core.

And we are drifting to oblivion.

Today, I have spent five and a half years in prison.

I am Galal el-Behairy.

Egyptian poet.

And I don’t know why I spent almost six years in prison.

Is it because I am a poet?

Or because I am Egyptian?

Galal El-Behairy, 2023