What does the label “women’s fiction” even mean? How much longer will women writers be asked how they do their jobs while also supporting a family? Why does historical fiction written by men get favorable coverage in the media while similar books by women are often dismissed?

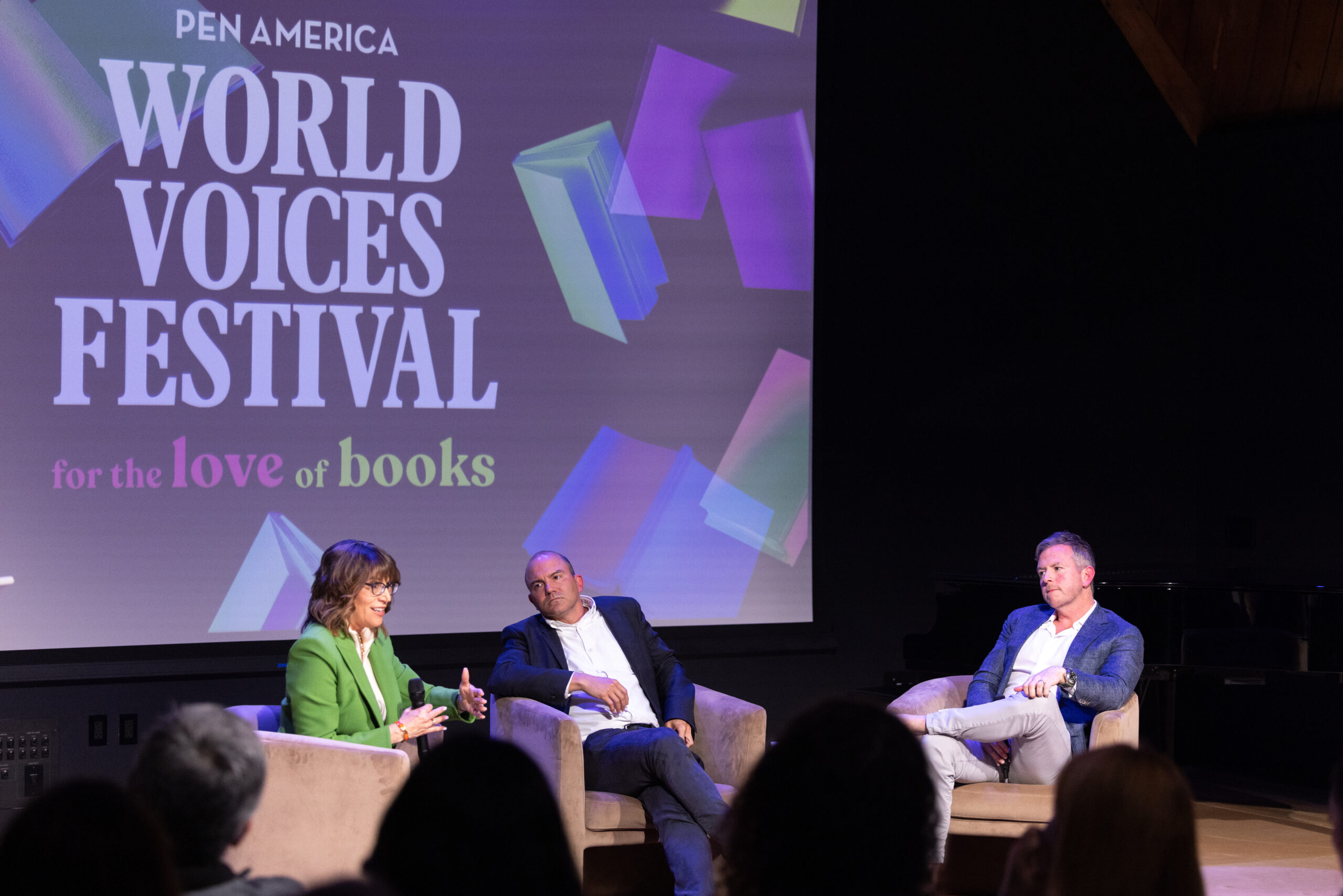

These questions and more were the objects of derision and much discussion at the panel, “Through Her Eyes: Exploring Gender Discrimination in Fiction.” Organized as a part of the 2025 World Voices Festival, authors Jodi Picoult and Fiona Davis joined writer Adriana Trigiani who moderated the panel at the AIA Center for Architecture in New York City.

Each with decades of experience and tens of books to their names, Picoult and Davis recalled and ridiculed all the boxes women who write are automatically placed into, from readers, publishers, agents, bookstores, and the occasional man next to you on the plane. Discussing their latest books—Picoult’s By Any Other Name and Davis’ The Stolen Queen—both historical fictions, the authors also talked about researching their leads, unexpected findings, and the challenges of accurate representation.

Children’s books or romance?

Jodi Picoult spoke about her experiences traveling as a writer: “Every day you sit next to someone, and it’s usually a man in this suit, and he says, ‘Oh, what do you do?’ And I’d say, ‘I’m a writer,’ and he’d go, ‘Children’s books?’ I said, ‘No.’ So he said, ‘Romance?’ And I mean, look, I am really fortunate. I have had an extraordinarily successful career that I worked really, really hard for. But the fact that I can be here at the top of this career, still being pigeonholed into the genres we think women should be writing is problematic.”

Fiona Davis shared a different kind of experience at book signings where women usually shared how much they love the book, while men retold the plot of the book to her. “I think it’s just a different matter of approach, where women want to share the emotion men want to show, ‘Hey, I read it. Here’s my book report.’”

Co-opting credit

Picoult and Davis in their latest books try to give credit where it is due—to women who deserved it but did not get it during their time. Picoult’s latest, By Any Other Name, is based on the theory that Aemelia Bassano, a prominent figure in 16th century England and widely regarded as the first English woman to assert herself as a professional poet, might actually be the author of some of the works attributed to Shakespeare. She said women were involved in theatrical productions but were hardly named or given credit for their labor.

Picoult: “I think women have been doing these things [being involved in theatrical productions] all along, sure. Even back in the Elizabethan times women were once doing it silently. … You have tons of unnamed women who were working silently in their gardens and with medicine and herbs, and who were working in the kitchens, and men came along and wrote down what they learned, and that was published under a man’s name. So there’s this co-opting of credit.

On writing “women’s fiction”

Fiction, especially historical fiction and “romantasy,” by women is generally received differently by agents and publishers. But fiction does not have a gender, argue the panelists, calling for the industry to take writing by women seriously.

Picoult: “I think that part of the reason that women are marginalized in general is because the things that women love are things that people diminish them for. When a woman writes about dragons having sex, it’s smut, but when George R.R. Martin does it, it’s fantasy. And that, I think, is something that we need to be talking more about, because—write whatever makes you happy. The world is hard enough, right?”

Davis: “Also the fact that so many historical novels are written by women, but a man writes a historical novel, he will most likely get a review in The New York Times Book Review. They will get written because they’re treated in a different way—it’s serious, even though you may have female characters or be about domestic issues.”

Want more?

Check out the panelists’ books:

- By Any Other Name by Jodi Picoult

- The Stolen Queen by Fiona Davis

- The Good Left Undone by Adriana Trigiani