Expanding the Web of Control

America’s Censored Campuses 2025

Key Findings:

Government censorship of free speech and academic freedom has reached unprecedented heights on U.S. campuses as lawmakers extend a web of political and ideological control over the sector.

More than half of U.S. college and university students now study in a state with at least one law or policy restricting what can be taught or how campuses can operate.

The Trump administration has weaponized multiple levers of state power to coerce colleges and universities into compliance with its ideological diktats.

PEN America Experts:

Program Director, Freedom to Learn

Sy Syms Managing Director, U.S. Free Expression Programs

Manager, State Policy, U.S. Free Expression Programs

Senior Analyst, PEN America

Introduction

There is no use in sugarcoating things. For higher education in America, 2025 was a year of catastrophe.

Across nearly every conceivable front – from state capitals to Capitol Hill and even on social media – America’s politicians have been a full-scale campaign against colleges and universities, with a concerted focus on speech. The toll is immense. Fear among faculty, students, and administrators is widespread. Self-censorship in teaching and research is rampant. Every week seems to bring a new law or directive that further threatens academic freedom and educational quality. Many professors are grappling with online hate and doxxing, at times instigated by elected officials. International students have been detained for their speech and threatened with expulsion from the country. Angry legislators are targeting any office or program even tangentially related to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). And campus leaders, buckling under the assault, have fired, suspended, or sanctioned scores of professors and staff, many for constitutionally protected speech. Some university presidents have been forced out or driven to resign. Many campus leaders feel they have no choice but to comply and try to strike deals with the federal government, even as they face mounting threats at the state level.

America’s Censored Campuses 2025: Expanding the Web of Control is a chronicle of this crisis. We build on PEN America’s past reports on this subject, but focus on higher education, rather than addressing both post-secondary and K-12 together, and examine the immense scope of both state and federal attacks on the sector. We describe direct forms of censorship – educational gag order laws that directly restrict teaching about such topics as race, gender, American history, and LGBTQ+ identities – as well as indirect forms of censorship – meaning, the state laws and policies that attack the practices and institutions that enable academic freedom to thrive, thereby indirectly chilling the climate for free speech. We see this in efforts to undermine shared governance and student activism, as well as in how legislators, under the guise of promoting viewpoint diversity, are trying to impose a new orthodoxy on college leaders and educators.

Numbers and taxonomy alone cannot capture the scale of what is taking place. The vast assemblage of legislation, policies, investigations, and threats, from state and federal governments, as well as various elected officials, has cast a web of control over campuses. Taken as a whole, they constitute a widening playbook for censorship that adds up to something more than the sum of its parts. Some states, notably Florida and Texas, have integrated mechanisms of censorship into virtually every dimension of their college and university systems, from how administrative leaders get selected to how faculty are promoted, from the way courses are approved to the specifics of course assignments. Other states – including Oklahoma, South Carolina, Indiana, and Ohio – are not far behind. Meanwhile, the federal government has leveraged its control over federal research dollars, Title VI investigations, and congressional hearings to bring some of the country’s wealthiest and most influential universities to their knees.

It must be noted that long before 2025, the federal government had taken actions that raised concerns for academic freedom and campus free speech. But in both quantity and quality, the second Trump administration’s assault on higher education is without precedent in modern American history. Private institutions have not been spared, nor those in liberal states. This is impacting the entire sector, from community colleges to the national accreditation system, from federal funding for research and student loan programs to efforts to advance student success, address antisemitism, and enable universities to recruit and retain international students and faculty.

When it comes to the expanding web of political and ideological control that has defined the past twelve months, virtually no institution of higher learning is safe.

While the current crisis has been greatly exacerbated by the actions of the second Trump administration, the seeds of these conflicts were sown years ago. Demographic changes on campuses, efforts to make higher education more inclusive, and an increase in knowledge production relating to the study of race and gender have long provoked rightwing criticism. On campuses, tensions manifested particularly at the intersection of free speech and new inclusion efforts, some tied to the growth of DEI offices. In turn, this spurred a growing national debate by the mid-2010s about the limits of speech on campus and the true civic purpose of higher education. In the political realm, some voices on the Right tended to frame the state of America’s college campuses in apocalyptic terms, ignoring reasonable concerns about student inclusion, the effects of targeted hate, and the need to redress legacies of discrimination and inequality. Meanwhile, some voices on the Left tended to downplay the real obstacles to dialogue and open exchange on campuses, particularly the feelings of isolation and silencing shared among conservative professors and students.

In a pluralistic democracy, for free speech and academic freedom to be upheld effectively, they must be upheld for all. But in recent years, campuses have often fallen short on these matters, feeding a perception that college and university leaders’ were either unwilling or unable to address growing free expression concerns. Rather than engaging with campus leaders, by 2021 Republican officials in a growing number of states turned decisively toward legislative solutions, seeking to impose new ideological restrictions on the professoriate, as if top-down, government-imposed directives, enforced by the fear of punishment, would make campuses better for conservative faculty and students, and for free speech, generally. There’s little reason to believe they have. Nonetheless, those efforts spread incrementally for four years. Then, with tensions on many campuses magnified by protests and encampments related to the war in Gaza, and increasing public scrutiny, the stage was set. With the second election of Donald Trump, the country was poised for the full-blown ideological campaign against the higher education sector we face today.

At their best, colleges and universities are vital engines of liberal democracy. Their faculty should inform and inspire the next generation of citizens and leaders, and their research should ignite innovation and discovery across fields. American higher education institutions have a particularly hallowed reputation worldwide for their traditions of open inquiry, academic freedom, and civic debate. And they have long powered local, state and national economies, all while attracting talent to American shores.

These traits that have made American post-secondary institutions unique and successful are all unquestionably in jeopardy at the start of 2026. This is not to say that they have not faced significant challenges in their evolution, but the current crisis seems less about forward-looking reform than about cudgeling the higher education sector into compliance with certain ideological orthodoxies. For years, campus leaders have struggled to sufficiently address their critics; now, they face a wholly different test of their core principles. Their autonomy and political independence, and the future of academic freedom and free speech on campus, hang in the balance.

The backbone of our research is compiled in our regularly updated Index of Educational Gag Orders, which we encourage you to consult. This comprehensive dataset tracks state-level legislation and policies since January 1, 2021. Using multiple tabs to organize measures by category, the Index includes educational gag orders affecting classroom instruction in K-12 schools and higher education institutions, as well as indirect censorship bills targeting higher education institutions. Bills may be included in more than one tab. Readers can organize and filter the data in each tab by various attributes including year, state, bill status, and type of indirect censorship, as applicable.

The report itself consists of six sections.

Section I offers a summary of the national landscape, highlighting topline numbers for the state bills, laws, and policies affecting higher education, and the chief threats against the sector in 2025 from the federal government.

Section II steps back from the current moment to consider the broader context for the growing crisis on campuses at the start of 2025, when President Trump returned to office. It situates recent events in the context of the long-running conservative critique of higher education, the increasing reliance of colleges and universities on federal funding, and the challenges related to free speech on campus that have worsened over the past decade. As we discuss, the reverberations on American campuses of the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza further weakened free speech and academic freedom norms, making the sector more susceptible to new political threats.

Section III explores the role that model bills developed by conservative think tanks have played in driving the current campaign against higher education. This section also describes the dangerous and even absurd consequences of the recklessness and speed with which new laws and policies have been enacted.

Section IV focuses on the principle of shared governance, which is, we argue, central to upholding academic freedom and free speech on campus. We chronicle the growing attempts by lawmakers to end or weaken it.

Section V analyzes the push by state and federal lawmakers to impose so-called “viewpoint diversity” on colleges and universities. In many instances, this seemingly anodyne term has become, in essence, a wolf in sheep’s clothing, disguising a concentrated effort to directly censor some viewpoints and amplify others, with little actual commitment to upholding diversity of thought on campuses.

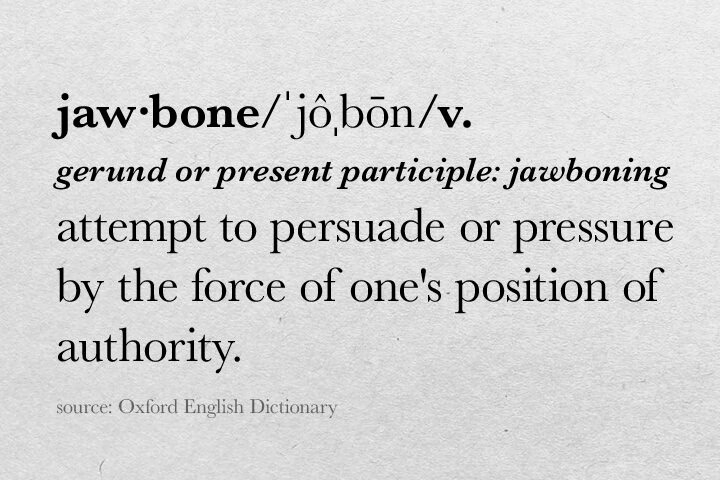

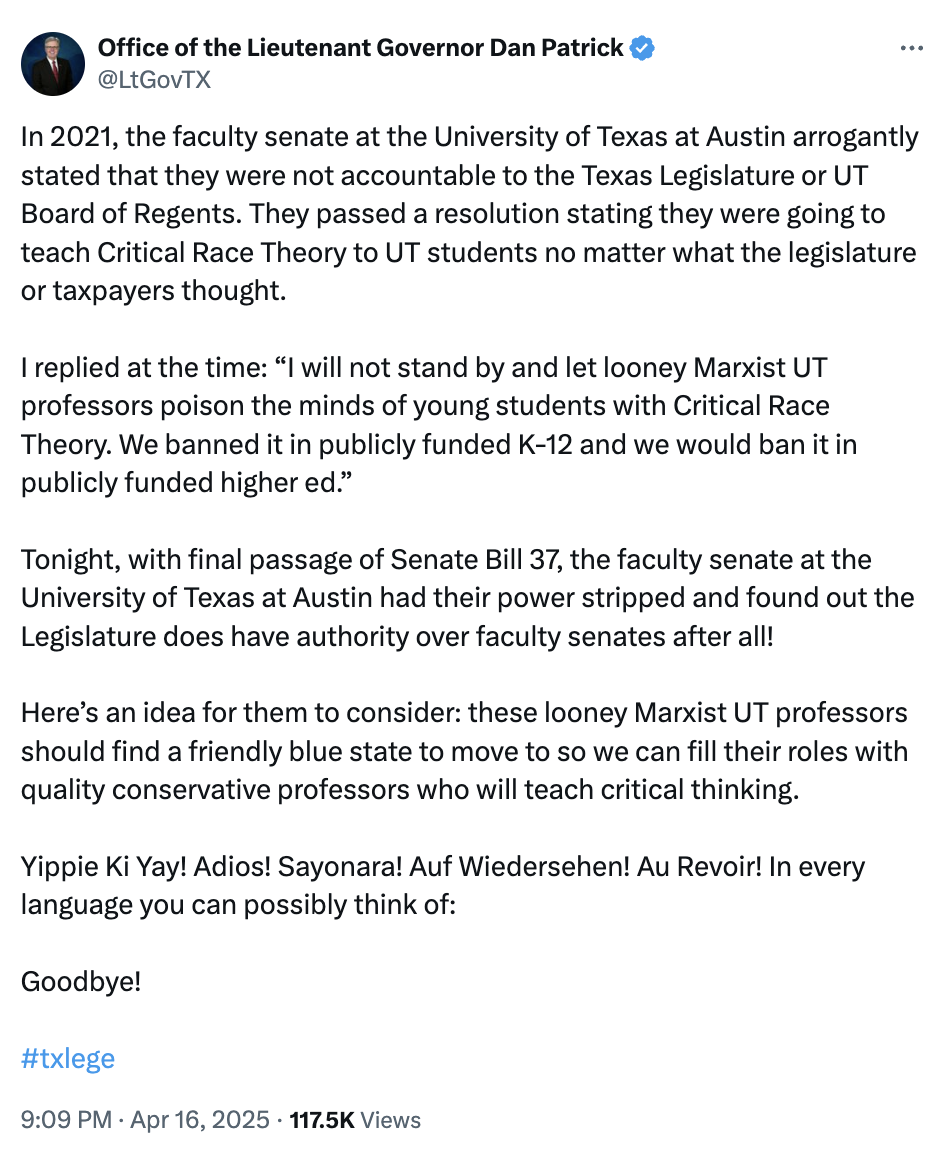

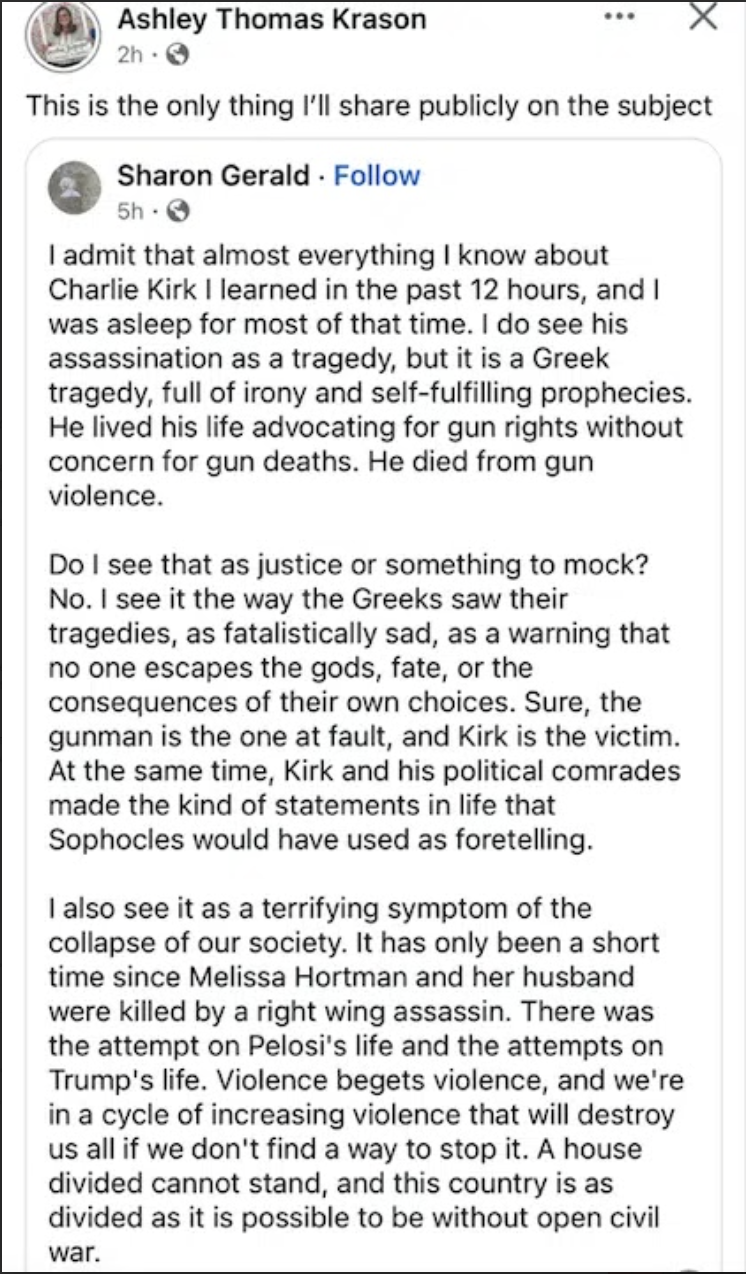

Section VI highlights the worsening practice of jawboning, and how responses to a single horrific event – the murder of conservative activist Charlie Kirk – reflect the vulnerability of colleges and universities to pressure from individual lawmakers and government writ large.

Finally, our Conclusion looks forward to the 2026 legislative session, with our predictions for how both state- and federal-level efforts to expand the web of political and ideological control over higher education will unfold in the months ahead.

This report includes two appendices: a Typology of Educational Censorship, where we lay out the categories we use to track legislation impacting colleges and universities; and a comprehensive list of New Higher Educational Censorship Bills and Policies in 2025.

You’ll also find links in this report to a new blog series we’ve launched, Snapshots of Censorship, where faculty share their firsthand accounts of government censorship.

Section I: Higher Education Censorship by the Numbers

2025 was a banner year for higher education censorship, and that is bad news for America’s students. This is the result of a relentless, years-old campaign to exert ideological control over college and university campuses – impacting academic research, teaching, and curriculum, as well as institutional policy and shared governance. The onslaught of legislation, policy, and jawboning targeting higher education has become the new normal for a growing number of state legislatures, as well as for the federal government under President Trump.

Map of Higher Education Restrictions, 2021-2025

State Legislation

Topline Numbers for State-Level Higher Education Censorship

- In 2025, state legislators introduced 93 bills across 32 states that would censor higher education.

- This includes 15 bills with educational gag orders, 56 with indirect censorship provisions, and 22 bills that include both.

- Of the 93 proposed bills, 21 bills – or 23% – became law in 15 states.

- 5 additional states policies restricting classroom teaching were issued or adopted in two of those states.

- State legislatures set 3 new records in 2025: the highest number of new laws censoring higher education enacted in a single year (21), the highest number of states enacting them (15), and the highest number of states enacting their first higher education censorship law (8).

- 23 states have now enacted laws or policies censoring higher education since 2021, and over 50% of university and college students in the U.S. are enrolled in a state that has enacted at least one law or policy censoring higher education.

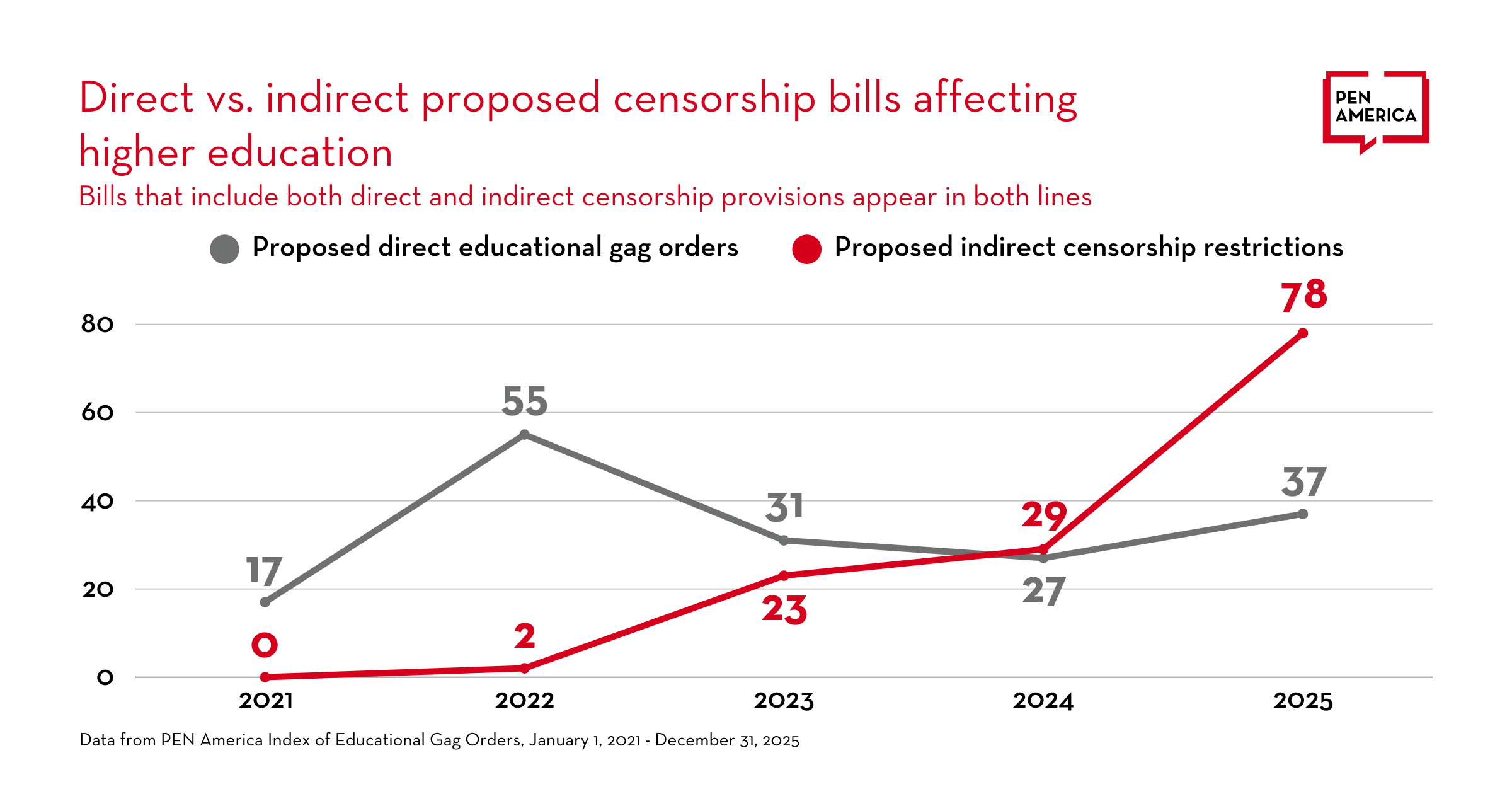

When PEN America started tracking educational censorship in 2021, we highlighted bills aimed at both K-12 and higher education, since legislators often lumped the two sectors together. The most common approach was what we termed educational gag orders, laws that directly censor topics in classroom teaching and educational materials. State bills of this type have continued to be proposed in each of the past five years, but as we noted in our 2024 report, America’s Censored Classrooms, legislators also began experimenting with a wider range of strategies and, as we put it then, “refining the art of censorship.” This meant looking beyond explicit gag orders, which directly censor classroom speech, and increasingly using indirect means to achieve their censorial goals.

In 2025, we saw this trend continue. As we detailed in a roundup of the 2025 state legislative sessions in July, new records were set last year for both direct and indirect forms of state censorship of higher education. After our final review of 2025 legislation, we can now say that 93 bills that would censor higher education were introduced across 32 states, including 15 with educational gag orders, 56 with indirect censorship provisions, and 22 bills that include both. Of these introduced bills, 21 became law, alongside 5 additional policies, raising the total number of states with new censorial laws and policies last year to 15. While some states are frequent offenders (e.g., Florida, Texas), 8 that passed bills or policies censoring higher education in 2025 did so for the first time (Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, New Hampshire, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wyoming).

All told, over the past five years, bills or policies censoring higher education have been enacted in 23 different states. Now, over 50 percent of university and college students in the U.S. are enrolled in a state that has at least one law or policy censoring higher education. This is a staggering figure that should give us all pause.

States that Enacted a Higher Education Censorship Law or Policy by Year

| Year | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| States | Idaho*, Iowa*, Montana*, Oklahoma* | Florida*, Mississippi*, South Dakota*, Tennessee* | California*, Florida, North Carolina*, North Dakota*, Texas* | Alabama*, Florida, Indiana*, Iowa, Tennessee, Texas, Utah* | Arkansas*, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas*, Kentucky*, Mississippi, Missouri*, New Hampshire*, North Dakota, Ohio*, Texas, Utah, West Virginia*, Wyoming* |

| Number of states that enacted a law or policy | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 15 |

Cumulative number of states with enacted laws or policies | 4 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 23 |

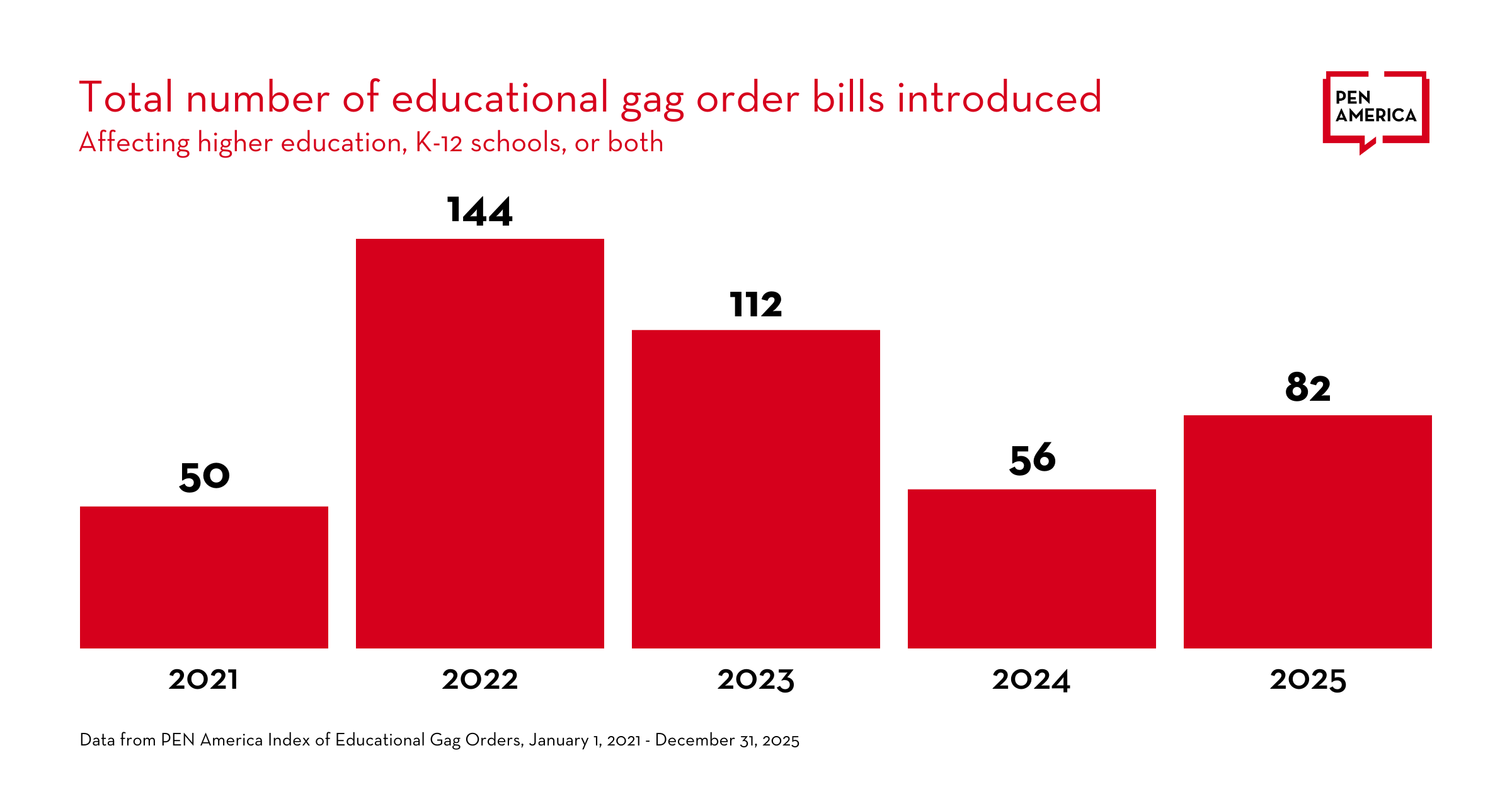

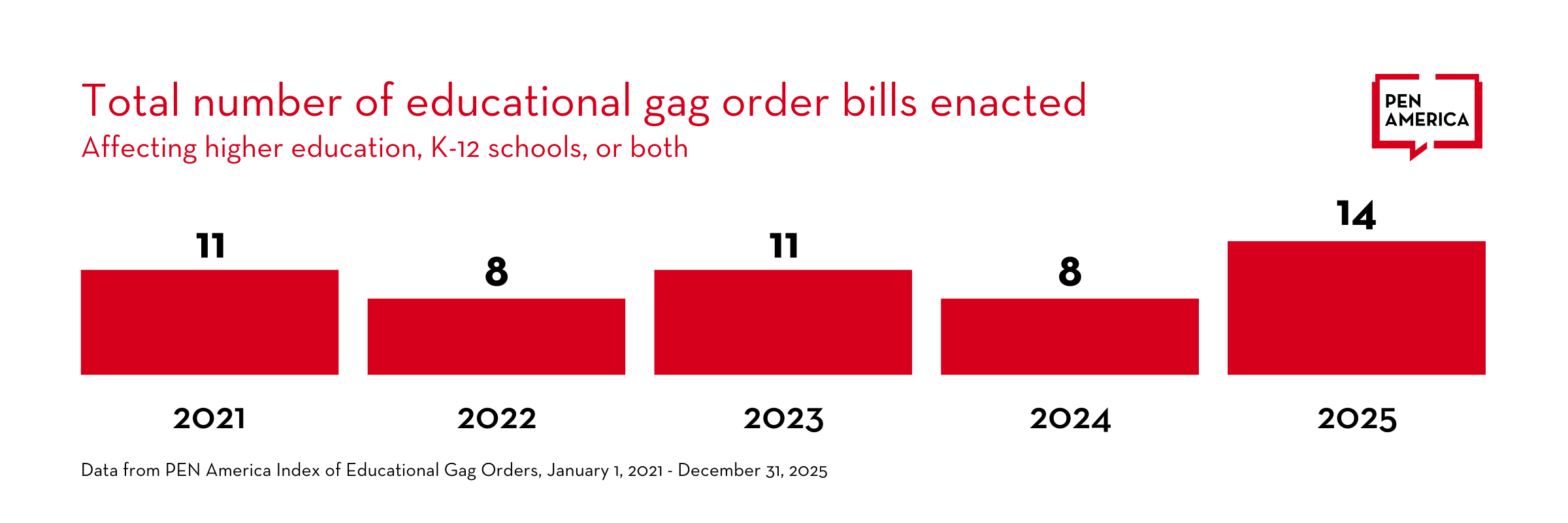

Direct Censorship: Educational Gag Orders

While state-level educational censorship has been ongoing for years, 2025 set a new record for the number of educational gag orders passed, whether targeting K-12 schools, higher education, or both. There were 82 educational gag order bills introduced in 2025, a significant reduction compared to the high-water mark set in 2022, which saw 144 such bills introduced. Despite the decline in absolute numbers of introduced bills, their rate of passage has steadily increased over the past four years. In 2025, 14 educational gag order bills passed into law, including 7 impacting higher education. In addition to bills passed by state legislatures, 5 educational gag orders were issued as state or university system policies. State lawmakers haven’t given up on these kinds of laws; they have become more efficient.

As the scale and scope of educational gag order laws have grown more brazen, legislatures have also increasingly disguised censorship or the true extent of the topics targeted. The same bill may even combine obvious censorship provisions alongside more covert but insidious restrictions. Ohio’s SB 1, for example, a sprawling 42-page anti-higher education broadside, includes mandates that every course demonstrate intellectual diversity, while also forbidding even voluntary diversity, equity, and inclusion trainings. This raises significant concerns for academic freedom, even though the law was passed under the guise of championing it.

Another example is Mississippi’s HB 1193, now subject to a partial preliminary injunction, which cloaks a sweeping gag order on any education that “increases awareness” of race, sex, color, gender identity, sexual orientation, or national origin by defining all such education as “diversity training.” Elsewhere in the now-enacted bill, the legislature directly lists a set of concepts related to gender and sex that cannot be promoted or endorsed – in other words, taught – in academic courses or elsewhere on campus.

In Texas, meanwhile, two major public university systems are implementing sweeping educational gag order policies that are quite explicit about their censorial aims. Faculty members and academic departments are now restricted in how they can discuss race or “race ideology,” gender identity, and sexual orientation without special permission from university leaders. These sorts of policies don’t carry the imprimatur of law, but they can cut off access to speech for tens of thousands of faculty and students. Indeed, the fact that in Texas thousands of course syllabi are now under administrative review confirms that they already have.

These educational gag orders are, however, just one part of the larger story of censorship that played out in 2025. Much of the action on the legislative front last year came in the form of indirect censorship: laws that undermine academic freedom and free expression rather than directly restricting classroom instruction.

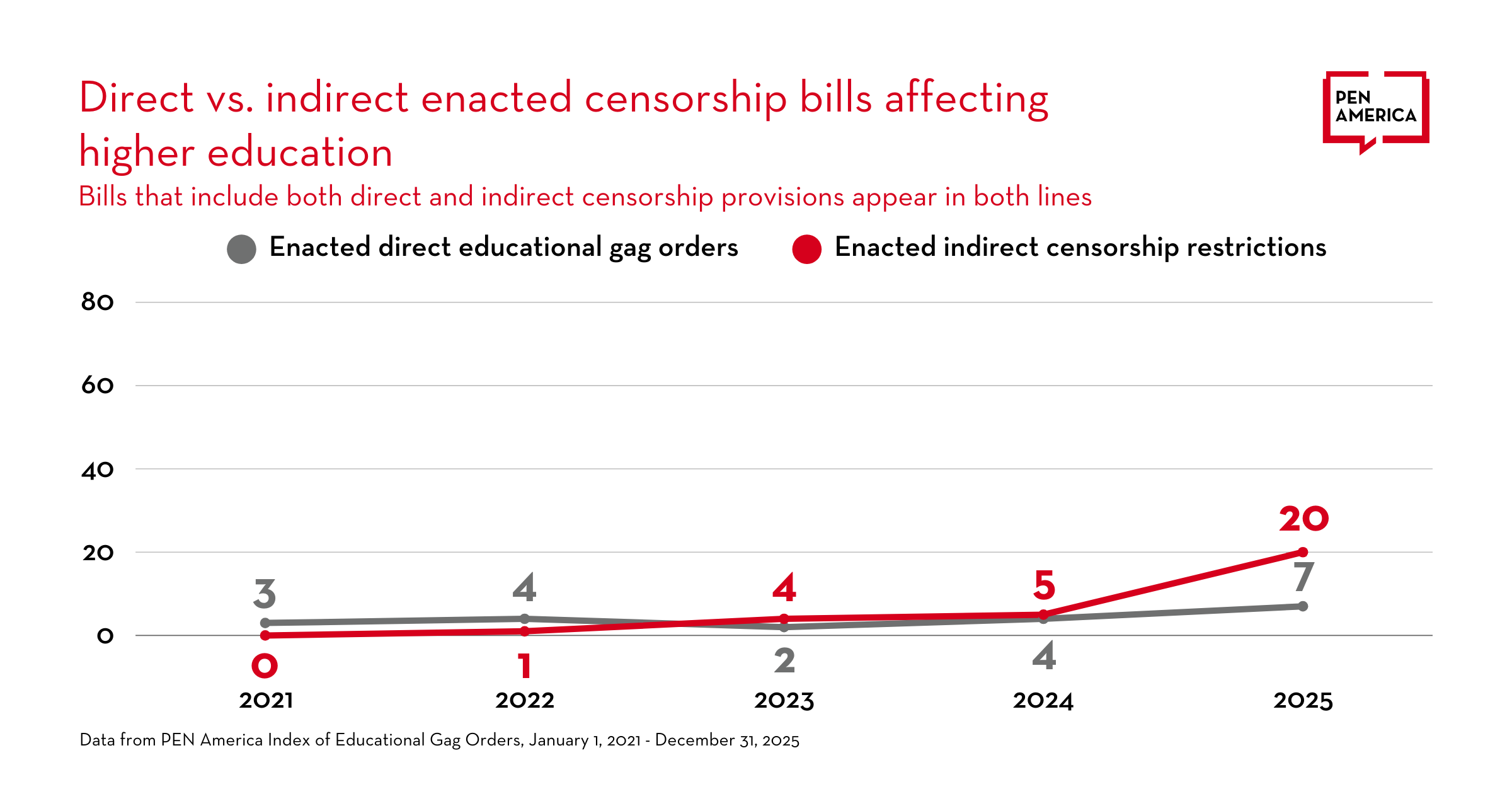

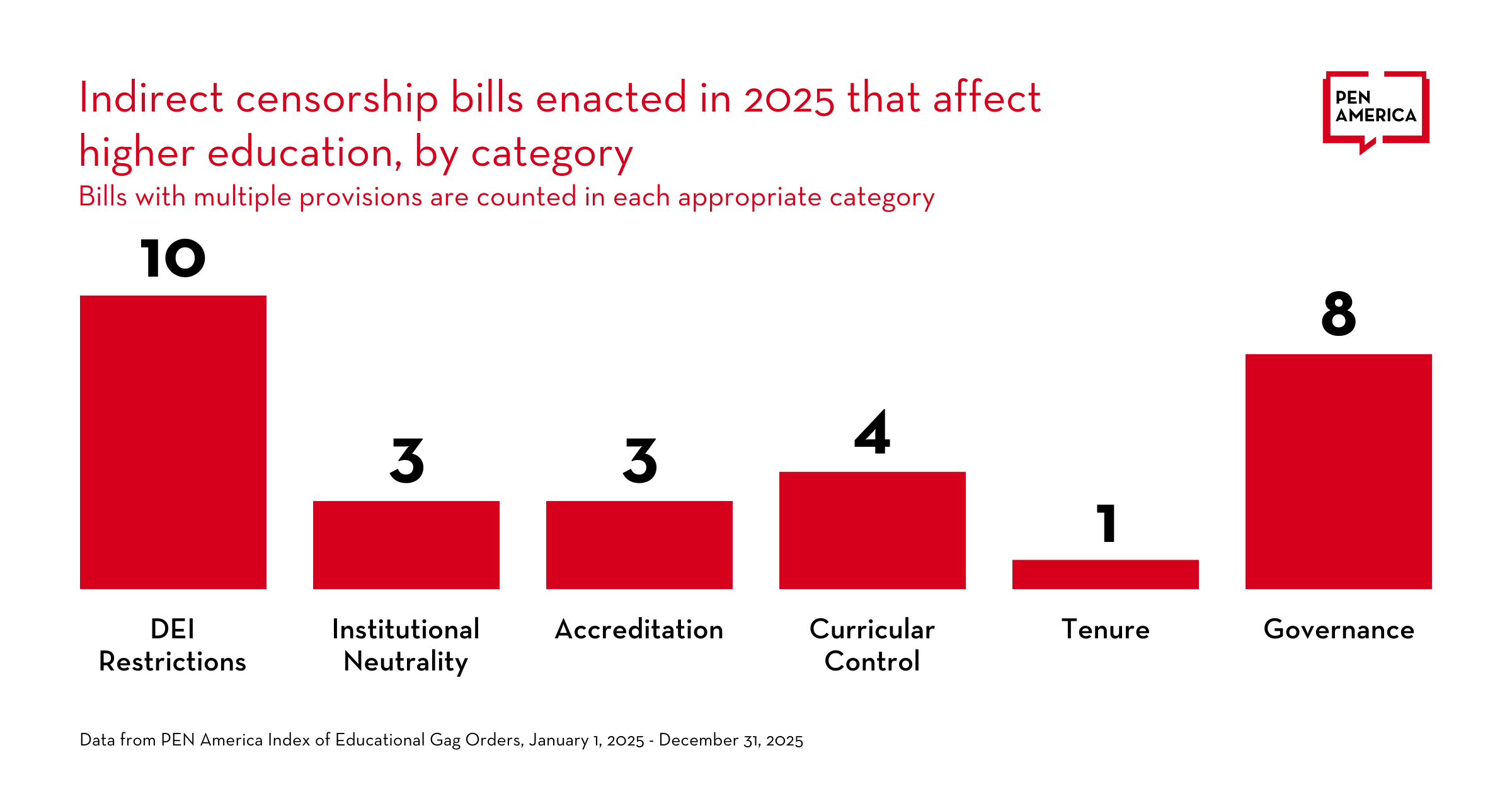

Indirect Censorship: Legislation that Undermines Institutional Autonomy

As first identified in our 2023 America’s Censored Classrooms report, indirect censorship bills restrict the mechanisms that protect academic freedom and erode long-standing norms of autonomy and self-governance in higher education. They undermine the ability of colleges and universities to fulfill their missions free from political interference, and instead seek to exert or facilitate ideological control over academic and programming decisions. For 2025, PEN America tracked state-level indirect censorship measures in six categories: curricular control, tenure restrictions, institutional neutrality mandates, accreditation restrictions, diversity, equity, and inclusion bans, and governance restrictions (see the Typology at the end of this report for more information). Many bills and policies contain more than one type of indirect censorship and may also include educational gag order provisions.

While governing boards and other decisionmaking bodies have an accepted role in crafting university and college policies, lawmakers, at best, lack the contextual knowledge to craft good policies on intricate institutional matters and, at worst, can be motivated to constrict academic freedom for one reason or another. Compounding these issues, the legal and political power that state policymakers inherently wield when they intervene by law or by threat routinely generates such high levels of fear and anxiety that faculty, administrators, and even students overcomply in ways that trample academic freedom.

Our research shows that legislators are more frequently adopting indirect means to achieve their end goal of censoring higher education, effectively expanding their web of control over the sector in numerous directions. While the number of indirect censorship bills proposed in state legislatures first surpassed the number of proposed educational gag orders in 2024, this difference magnified in 2025. Indirect censorship measures exploded in popularity, with state legislators introducing more than twice as many of them as they did educational gag orders (78 vs 37).

In total, 20 of these indirect censorship bills were enacted into law, impacting a range of college and university operations. The enacted laws include Indiana’s HB 1001, which relegates faculty senates in the state’s public universities to an “advisory” role only in academic affairs, as well as Idaho’s SB 1198, which does not exactly prohibit professors from teaching a course on “critical theory,” but does forbid them from making that course a required part of an academic major, minor, or certificate, with minimal exceptions. And it includes Kansas’s SB 78, which allows universities to sue a higher education accreditor if they are punished by the accreditor for adhering to a state law, a handy weapon for Kansas universities, given how many of the state’s laws violate accreditors’ standards on academic freedom.

The fact that 20 of 78 indirect censorship bills introduced in 2025 passed into law is a remarkably strong rate of passage (26%), suggesting just how popular this type of legislation has become with lawmakers in states with Republican legislative control. And it is easy to see why. Once you strip away every sort of protection a professor has, there is no need to directly restrict their speech. A vague threat will be more than sufficient. This dynamic, which is discussed at length in Section VI, was on full display after the killing of conservative activist Charlie Kirk. It also reflects what lawmakers and think tanks interested in advancing ideological control over academic teaching at colleges and universities have apparently learned over the last four years: Given the historic strength of support for academic freedom across the country, they need to go beyond direct gag orders and prohibitions if they want to achieve their ends.

Still, all of this state-level activity does not capture the full scope of threats aimed at colleges and universities last year. That is because in 2025, for the first time since PEN America began tracking the war on campus free expression, the federal government has fully embraced this effort.

Once you strip away every sort of protection a professor has, there is no need to directly restrict their speech. A vague threat will be more than sufficient.

Federal Overreach

In early 2025, just a few weeks before President Trump’s second inauguration, PEN America made four predictions about what the federal government would do next. First, that it would launch an unending series of congressional and Title VI investigations designed to bully university leaders into submission. Second, that it would leverage concerns over campus antisemitism to censor faculty and chill student speech, especially that of international students present in the United States on student visas. Third, that it would use its control over federal research dollars to bring universities to heel. And fourth, that it might weaponize the higher education accreditation process to force educators to teach “pro-American” content.

Of these four predictions, only the last has not (yet) come to pass. The others have proved depressingly accurate, though even we did not anticipate the sheer ferocity of the federal government’s assault. That is in part due to the assumption – a mistaken one, as it turned out – that while the Trump administration might stretch the Constitution, it would not violate it. But that is precisely what happened, as the courts have determined again and again. Whether those courtroom victories will ultimately amount to anything, though, is less clear. Just because a university eventually regains lost federal funds does not mean that it has not borne significant costs, including an erosion of academic freedom and political independence. There is also no guarantee that it will receive the level of funding it expects in the future, or even any funds at all, and no promise that it won’t face a different sort of challenge. Universities are operating in a climate of profound uncertainty.

The Federal Government’s Attack on Higher Education in 2025 by the Numbers

| Title VI investigations into universities launched by the Dept. of Justice and Dept. of Education since January 2025 | 90+ |

| Federal research dollars targeted for cuts from grants previously awarded to institutions | $3.7 billion |

| Estimated annual cost of NIH and NSF funding cuts, in the form of decreased U.S. economic output | $10–16 billion |

| The estimated number of clinical trial participants affected by cuts and funding disruptions by the NIH to 383 clinical trials | 74,000 |

| Universities that have cut a deal and had funding restored or have remained eligible for federal funding | 6* |

| The number of universities (including Harvard and Yale) that the State Department has proposed suspending from a federal research partnership program because they engage in diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) hiring practices | 38 |

| Total that US universities agreed to pay to the federal government in settlements since January 2025 | $305 million** |

| Fine sought by the federal government from the University of California | $1.2 billion |

| Lawsuits filed challenging Trump administration education policy | 56 |

| Executive orders that directly target or otherwise impact higher education | 19 |

| Number of international student visas revoked by the State Dept. | 8,000+ |

| Percentage of institutions reporting a decrease in new international enrollment | 57% |

| Decrease in the number of new enrollments of international students (first time in college) | 17% |

* Including Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Northwestern University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Virginia.

** Universities that agreed to pay settlements directly to the federal government include Northwestern University, Cornell University, and Columbia University. In addition, Brown University is required under its settlement to pay $50 million to state workforce development organizations, Cornell University is required to devote an additional $30 million to agriculture research programs, and Columbia is required to pay an additional $21 million to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Note: Information compiled from the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, and the Federal Register, and from analysis by Education Week, Inside Higher Ed, the Center for American Progress, NAICU (the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities), Higher Ed Dive, and various media reports.

From executive orders and memos, to investigations, the withholding of funds for research and financial aid, and efforts to detain, deport, or deny visas to international students and academics, the federal administration has weaponized every imaginable lever to bring the higher education sector to its knees. We see this in the destabilization of numerous federal agencies whose interactions with scholars, universities, and academia were previously routine; the fear that the use of certain words in scientific research proposals could lead to lost funding; the way that the Trump administration’s shifting interpretations of civil rights and anti-discrimination laws sow confusion; the cancellation of funds for foreign language training, area studies centers, and international exchange programs; orders from the Center for Disease Control and other agencies to suspend external publications to comply with the administration’s ideology; and reports of tightening control over civilian professors and curricula at military academies.

Even during the height of McCarthyism, when Cold War paranoia consumed the country’s universities, the federal government’s actions primarily focused on individuals and did not compare in either quality or quantity to the instruments of control, fear, and censorship deployed against the entire higher education sector in 2025. As our on-going research has shown, the groundwork for these federal actions was laid years ago in state capitals across the country – where legislative censorship has also continued to grow. The range of strategies in the federal toolbox and the high level of coordination among different departments will be discussed in greater detail in the ensuing sections of this report. As new attacks roll out weekly, the costs to us all keep rising, whether in the numbers of grants cut, the foreign students who have left or not enrolled, the dollar amounts in penalties being demanded of public and private universities, the weakening of scientific research, or the narrowing of students’ educational opportunities.

Section II: The Growing Crisis on Campus Before 2025

As PEN America’s previous annual reports have shown, the campaign to control what is taught in the U.S. education system is not new; so why, then, has the past year seen such a dramatic erosion of institutional autonomy and a sector willing to bend to political pressure?

The attacks on higher education just in 2025 – whether from state legislators or federal agencies or even the general public – and the sector’s apparent openness to abdicating its agency and principles, come as the result of three distinct trends that have been years in the making. These include the decades-old conservative critique of higher education, which has recently gained new energy and adherents; the increasing financial reliance (and consequent vulnerability) of the sector on the federal government; and the growing challenges to free speech on campuses in the mid-2010s. These three trends eroded the foundation of higher education, weakening public trust in the institution. All that was needed to trigger a collapse was a spark, which came in the fall of 2023 in the form of the war in Gaza. The fissures in campus communities that were brought to the surface were then exploited by political actors eager to weaponize genuine concerns about discrimination, safety, and free speech on campuses, in order to undermine the sector as a whole.

The effects of the Israel-Hamas War and subsequent campus protests reverberated throughout the 2023-24 academic year and into the fall 2024 semester, causing widespread anxiety and fatigue among students and faculty, as well as college and university leaders. Heightened scrutiny from both state and federal governments and the constant threat of high-profile negative press, as well as fear among administrators that their own actions might draw fire, worsened this state of affairs. As a result, the lines that ought to distinguish what speech is permissible or not on campus seemed to become harder to distinguish, perhaps most so to the individuals charged with drawing them.

When President Trump took office in 2025, the higher education sector was already vulnerable, the lines around free speech on campus fraught and weakened by years of censorial state action and growing public skepticism. This climate made the country’s colleges and universities uniquely susceptible to new federal efforts to expand direct government control.

The Conservative Critique of Higher Education

While this report focuses on 2025, the roots of the current catastrophe run deep. America’s colleges and universities have been embattled institutions at numerous points in the last century. During the First World War, critics accused academics of being unpatriotic and purveyors of “foreign” ideologies like Marxism and anarchism. These criticisms diminished somewhat during the 1940s, but resumed with a vengeance during the Second Red Scare of the 1950s. During the McCarthy era, hundreds of professors lost their jobs or had their careers permanently stunted because of their scholarship or refusal to denounce colleagues. Self-censorship among professors was pervasive, often with the knowledge and encouragement of campus administrators. So great was the paranoia, recounts the historian Ellen Schrecker, that some scholars stopped using words like “capitalism” and “revolution” in the classroom.

But even after the end of the McCarthy era, criticism of higher education continued to grow. Public intellectuals like Russell Kirk and William F. Buckley, who otherwise had markedly different opinions about academic freedom, agreed that professors were increasingly un-American, if not downright corrupt. Professors, they argued, had no sense of truth or beauty, having traded eternal truths for passing fashions. As a result, academic freedom had lost its purpose. Of course, even in the 1950s, this critique of colleges was not entirely new. But Kirk and Buckley’s legacy was laying the foundation for a populist critique of higher education, a move that sought to restore to the academy the simple virtues of patriotism, individualism, and love of God. This critique would prove remarkably adaptive, and throughout the 1960s and 1970s was seemingly able to diagnose every prevailing anxiety of the day, whether from civil rights or anti-war activism, feminism, decolonization, or political correctness run amok.

Then there’s the influence of James Burnham, a philosopher frequently cited by those advancing the “burn-it-all-down” nihilism that drives some of the MAGA movement’s more vicious attacks on the higher education sector. Like Kirk and Buckley, Burnham was suspicious of universities, warning that as the economy grew more complex, power would become concentrated in the hands of unelected and unaccountable experts and credentialed elites.

Coupled with rising anti-immigrant and white nationalist sentiment in response to the twentieth century’s civil rights movements and demographic changes on campuses, Burnham’s ideas helped fuel the populist ideologies that undergird much of the conservative critique of higher education today.

The Rise of Federal Power

It was amid these mid-century critiques of academic freedom and the professoriate that, with bi-partisan support, the federal government massively expanded its investment in higher education. The G.I. Bill (1944) first brought the federal government into large-scale funding of college tuition, and this commitment continued into the 1960s, with the passage of the Higher Education Act, and early 1970s, with the expansion of Pell Grants. During the same time, the federal government was investing enormous sums of money in scientific research through the National Defense Education Act (1958) and a Johnson-era executive order, which ensured that money was distributed to small and large institutions alike. Over the following decades, the federal government became a major underwriter of biomedical research, engineering, physical sciences, area studies and foreign language training, energy and agricultural sciences, and many other disciplines deemed critical during the Cold War.

The implications of these developments were vast. With more money and more students came the need to hire more faculty. This market demand blunted significantly the effects of McCarthyism on the academy, since professors persecuted in one university could often find refuge in another. In that respect, the government’s attempts to exert control over the professoriate and expand the education sector were at cross-purposes.

Federal support came with two conditions, however. The first was the statutory requirement that, as a condition of qualifying for Pell Grants, work-study funds, and other federal programs, students must attend an institution recognized by a higher education accrediting body. Otherwise, Congress feared, students might spend their publicly subsidized tuition dollars at, for example, predatory diploma mills or fiscally insolvent institutions. This rule protected students and encouraged colleges and universities to behave responsibly; it also gave those accrediting bodies significant influence over the higher education sector.

The second condition was via federal civil rights laws, which all universities – public and private – must follow in order to receive federal financial assistance. The most pertinent of these laws for campuses are Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in programs or activities receiving federal financial assistance, and Title IX (adopted as part of the Education Amendments of 1972), which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in programs or activities receiving federal financial assistance. Universities and colleges found to have discriminated on any of these grounds, or to have knowingly allowed others to discriminate, can lose out on federal funding for research, Pell Grants, work-study programs, or any other earmark.

These increases in federal support and oversight left the sector – and large research universities in particular – dependent on the government’s largesse. Over time, college and university administrators sought out alternative revenue streams and cost-savings measures, but each came at a price. For example, hiking tuition raised revenue, but also angered many Americans for whom access to higher education was considered a public good. And adopting a “student-as-customer” business model helped enrollment, but arguably undermined educational quality. Campuses also tried to rein in expenses by shifting away from hiring full-time, tenure-track faculty and toward a part-time and contingent labor force; between 1987 and 2021, the overall percentage of tenured or tenure-track faculty declined nationwide from 53 percent to just 32 percent. Contingent faculty are far less expensive, but their lack of job security means they’re less able to push back against administrators’ demands, less able to advocate for academic freedom, and less able, as well, to provide students with the mentorship and support they need.

In the process of implementing this carousel of strategies, administrators undermined the principle of shared governance in order to concentrate decision-making power in their own hands. They were accused of inflating their administrative ranks and mimicking strategies from the corporate sector. While these choices may have helped with the financial challenges of the sector, they did enormous damage to the job protections that undergird academic freedom and left the sector more vulnerable to critiques of mismanagement.

Growing Challenges to Free Speech on Campus

These multiple pressures left the sector ill-prepared for the new challenges that emerged around 2010, when social polarization weakened support for higher education within the Republican Party. A declining number of conservatives in the professoriate, which denied academia some of its most persuasive advocates on the political Right, and dramatic increases in the cost of tuition and student debt, led many to question the value of college degrees. Meanwhile, conservatives developed a potent line of criticism against the sector, accusing it of being an incubator for harmful ideas run by out-of-touch elites more interested in coddling students than educating them.

Then, around 2015, a new national debate over free speech on campus emerged. Many elements contributed to this including a string of high profile attempted deplatformings, ill-advised administrative responses where students and faculty were punished for what should have been protected speech, and intense media scrutiny. Campuses became flashpoints for conflict, with social media feeding the fire and fomenting public pressure on universities to react.

Many of these incidents were driven by liberal students and directed at conservatives, exacerbating the existing impression that conservatives were unwelcome on college campuses. As PEN America summarized in reports published in 2016 and 2019, campuses’ attempts to address discrimination and advance inclusion through concepts like trigger warnings or safe spaces may have been well-intentioned, but nonetheless often had the effect of stifling academic freedom and free speech. The same was true of certain DEI offices or programs, if they enforced a rigid orthodoxy around race, gender, and social justice. At the same time, many campus controversies from this period involved genuinely hateful speech, leaving administrators, faculty, and students unsure of how to respond. Universities cannot teach when speech is censored, and students cannot learn when they feel unsafe or unwanted; as PEN America has long argued, it is a delicate but necessary balance to strike. Unfortunately, a lack of preparation, including inadequate procedures to respond to students’ demands, often resulted in knee-jerk reactions, rather than dialogue and mutual respect from all involved.

By the time that President Trump first took office in 2017, these tensions were worsening. The period saw an increase in hate crimes and intensifying polarization on campuses, including accusations about the politicization of teaching and research, and instances where protestors shut down speakers. One of the most infamous of these deplatformings – when Charles Murray was invited to speak at Middlebury College – turned violent. A student journalist explained the flare of tensions as reflective of the political context, “After Trump was elected, there was really a lot of tension on campus. There was a need for some outlet, for some sort of event, or demonstration that students could rally around.”

The same could be said about the country more generally. The summer of 2020 saw mass Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, and the public reckoning with racism led many institutions in various fields to adopt new curricula, training, and commitments to address systemic racism. Along with The New York Times’ 1619 Project, published the year prior, these formal and informal changes in schools, colleges, and workplaces became the focus of pointed ideological disagreement. As colleges and universities committed to combating racism, some conservative activists took up the existing conservative critique of higher education and adapted it, targeting race, ethnic, and gender studies, as well as campus inclusion programs. Ironically, they turned against freedom of speech on campus even while continuing to claim they were defending it.

In September 2020, with the election just weeks away, President Trump issued Executive Order 13950, “Combatting Race and Sex Stereotyping.” It included a list of nine so-called “divisive concepts” that recipients of federal funding were prohibited from promoting. Trump would go on to lose the election and President Biden would rescind the executive order on his first day in office.

But by then, the very same list of divisive concepts was already popping up in state-level bills across the country. These educational gag orders, as PEN America called them, proved popular with Republican policymakers. Between 2021 and 2023, over 300 gag orders were introduced targeting K-12 or higher education, with their focus overwhelmingly on restricting teaching about race, gender, and sexuality. Powering their adoption was a widespread rhetorical campaign against “critical race theory” – a scholarly movement that began in law schools in the late 1970s. As the term entered the political mainstream, it became a catch-all for everything wrong on college campuses, alongside “DEI.” One need not endorse every DEI-related office or program that has existed in higher education to recognize that outright bans, driven by government actors, pose their own threat to the political independence of the academy writ large.

By mid-way through the Biden administration, the chilling of campus speech for one reason or another was following a familiar pattern, generally driven, on the one hand, by cultural pressures on faculty and administrators to avoid topics that might be disfavorable to left-leaning students, and on the other, by a political threat from state legislators who were passing laws to censor and control academic teaching. Around the country, faculty expressed concerns with one or the other of these censorial pressures, sometimes both.

In this climate, students often chose self-censorship, declining to share their views on controversial topics. Some faculty and administrators were also complicit, both by creating new tools for censorship and by actively deploying them against students’ speech. According to a 2024 report by Heterodox Academy, which analyzed data from 2019 to 2022, students across the nation were consistently hesitant to share views on controversial issues, regardless of their geographic location or institution type.

The Israel-Hamas War

These cultural and political dynamics on campuses changed dramatically following the Hamas-led attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and Israel’s subsequent air and ground campaign in Gaza. These events triggered an enormous wave of protests, most notably in the form of encampments and building occupations, accompanied by intense criticism of Israel from students, faculty, and others associated with the academy – which generated accusations of antisemitism and demands that universities crack down on these activists.

From coast to coast, these tensions became a daily reality on many campuses, with instances of antisemitic, anti-Arab, and anti-Muslim hate and violence, as well as clear censorship of both pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli views. The combined horror of the Hamas-led attacks on October 7, the taking and subsequent treatment of hostages, the massive Israeli military response and its devastating toll on civilians, infrastructure, and culture in Gaza, and the failure of the international community to put a stop to the violence increased tensions on U.S. campuses. These concerns were made more urgent by a series of much-discussed reports from major international human rights groups, including in Israel, which argued the Israeli government had committed war crimes and other atrocities, including genocide. Student protestors often pointed out the complicity of the US government in these atrocities.

Almost immediately after the attacks of October 7, the very real issue of rising antisemitism was seized on by numerous politicians to advance critiques of campus free expression. As PEN America discussed in a previous report, some state lawmakers quickly introduced legislative proposals to censor speech deemed antisemitic. At the federal level, over the ensuing year, multiple college and university leaders were hauled before the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, forced to answer antagonistic questions and respond to lawmakers’ grandstanding while testifying under oath. Some were pressured to denounce their own faculty. Others were chastised for defending free speech or negotiating with student protesters. At least two high profile university leaders, Harvard’s Claudine Gay and the University of Pennsylvania’s Liz Magill, resigned shortly thereafter. And it seems likely that there was a link between the disastrous testimony of Columbia’s Minouche Shafik before the Committee on April 17, 2024, and her decision to end negotiations with student protesters one week later. It was also around this time that Rep. Mike Johnson, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, visited Columbia’s campus to demand that Shafik resign. Later that summer, he would get his wish.

Regardless of the political motivations that propelled these congressional hearings, there were unquestionably a troubling number of instances of antisemitic and anti-Israel discrimination on college campuses. In one especially egregious example, the University of California, Berkeley is alleged to have refused to hire a dance professor because she was from Israel. Internal messages, made public as part of the professor’s lawsuit, show the department chair seemingly caving to student anger at the prospect of an Israeli faculty member on campus: “My dept cannot host you for a class next fall… Things are very hot here right now and many of our grad students are angry. I would be putting the dept and you in a terrible position if you taught here.” The professor alleged discrimination and an internal investigation by UC Berkeley agreed with her. In December 2025, UC Berkeley agreed to pay the professor $60,000 in a settlement. The chancellor issued her an apology and invited her back to teach.

In another case, a Cornell student threatened to murder his Jewish classmates. At the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), student protesters occupying a portion of the quad barred any student who declined to disavow Israel from access to certain ordinarily available campus areas and programs; a federal judge subsequently found UCLA liable for violating the Jewish student plaintiffs’ First Amendment rights under the free exercise of religion clause when the university failed to ensure that either all students or, in the alternative, no students were granted access, regardless of religion. A University of Delaware student attacked a campus Holocaust memorial while shouting “Fuck Jews” and “The Holocaust should have happened.” At Stanford, an instructor asked the Jewish and Israeli students in his class to stand up and move to a separate area of the classroom. He then said “This is what Israel does to the Palestinians.” He went on, “How many people died in the Holocaust?” When a student answered, “Six million,” the instructor said, “Colonizers killed more than six million. Israel is a colonizer.” In this period, thousands of Jewish sites on campus, including synagogues, Hillel centers, and fraternities, were also protested and/or vandalized.

Alarming as these incidents were, there are ways that colleges and universities could have responded to them that are consistent with academic freedom and the principles of free speech. Too often, any criticism of Israel was conflated with antisemitism, which seemed to spur overly-aggressive responses to protests that were otherwise peaceful in nature. Between October 2023 and January 2025, repression of students and free expression on campuses reached levels unseen in recent decades. Some pro-Palestinian students were punished for expressive activities, and some student journalists were even sanctioned for covering protests. Other students were subject to grueling investigations, lost their meal plans and access to campus housing, or endured withering public criticism, leading to doxing and rescinding of employment opportunities. In some instances, university leaders rewrote the student disciplinary process on the fly in order to smooth the path to punishment. In other cases, decades old debates about “institutional neutrality” were reignited as some university leaders got nervous about their own speech, or faced external pressure to exert control over what their faculty and academic departments might express about the war. Campus leaders were met with public and private scrutiny from their boards, alumni, and at times, elected officials. It seemed no matter which path presidents took in responding to these campus conflicts, criticism abounded.

Individual faculty were not spared either. In one case, Jodi Dean, a political theorist at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, was temporarily barred from campus because of a pro-Palestine blog post. Raz Segal, an Israeli academic and leading expert on the Holocaust, lost a job offer at the University of Minnesota because he accused Israel of genocide. After criticizing Israel during an interview with the news program Democracy Now!, Columbia professor Katherine Franke was investigated by the university’s Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action. The toll of the investigation was so heavy, Franke would later say, that she stepped down from her position in early 2025, arguing that it was not really her choice to retire, but “a termination dressed up in more palatable terms.” Kareem Tannous, a business professor at Cabrini University, lost his job over anti-Israel comments he made on his personal social media account. So did Maura Finkelstein, who had been a tenured professor of anthropology at Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania.

The Challenge of Adjudicating Antisemitism on Campus

Antisemitism from across the political spectrum has significantly increased in recent years, and complaints of antisemitism have surged on college and university campuses in particular since October 2023. Administrators have faced significant challenges adjudicating these cases in part because of disagreement as to how to define antisemitism. Speech critical of Israel and/or Zionism is not inherently antisemitic. Even though some such speech can cross the line into antisemitism, there has long been a dangerous tendency to conflate anti-Israel expression with anti-Jewish bias. The result of this conflation has been that core political speech critical of Israel is being chilled.

This question is especially consequential for how colleges and universities respond to complaints alleging violations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bars discrimination based on race, color, and nationality. Although Title VI does not expressly mention religion, the statute has been interpreted to forbid discrimination of religious groups where unlawful conduct is based on actual or perceived shared ancestry or ethnic characteristics of that group. Thus, Jews (shared ancestry) potentially can be a protected class under Title VI, as are Israelis (national origin), and both groups are protected under other federal and state laws (and constitutional provisions) that prohibit discrimination based on religion and/or national origin. By contrast, Zionism, defined as a political belief or ideology, would not render its supporters a protected class, unless it could be shown, for example, to serve as a proxy for Israelis, Jews or Judaism. This in turn can inform whether there has been discriminatory intent when investigating alleged violations of civil rights laws or anti-discrimination policies.

Distinguishing between antisemitism and political and ideological criticism of Israel has also been complicated by an effort to codify a specific and controversial definition of antisemitism — from the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) — in state and federal law, as well as in campus policies. This is because in addition to its core definition of antisemitism as pertaining to hatred toward Jews, the IHRA definition includes 11 “illustrative” examples of what could be antisemitism, 7 of which involve speech critical of Israel. These include, for example, claiming that the State of Israel is a racist endeavor (which the definition equates with denying Jews the right to self-determination), and “applying double standards by requiring of [Israel] a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation.” By contrast, other respected definitions of antisemitism expressly reject that a number of the IHRA definitions’ examples are per se antisemitic.

Nonetheless, since 2019, the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) has required that the IHRA definition, including its examples of anti-Israel expression, be considered in determining the existence of antisemitic discriminatory intent when enforcing Title VI. And although the definition does not insist that its illustrative examples always constitute antisemitism, they are worded in a broad and vague way that makes them vulnerable to the vagaries of interpretation. In other words, incorporating this definition into laws and policies that carry disciplinary and legal sanctions opens the door to enforcement that curtails speech critical of Israel’s government, its military, or its actions, laws, or policies. Indeed, the institutionalization of the IHRA definition to adjudicate campus discrimination has been opposed by numerous free speech groups, including FIRE, the AAUP, and the ACLU, and even its original lead drafter, Kenneth Stern, because of its clear chilling effect on speech about Israel.

None of this is to say that there have not been serious challenges with surging antisemitism on campuses that demand addressing by campus leaders. It is also important to recognize that there are significant numbers of Jews for whom Zionism – meaning, for example, support for a Jewish homeland which includes modern-day Israel – is an integral part of their genuinely held religious beliefs. Many Jewish students who hold those beliefs have felt targeted based on their religion on campuses, particularly by efforts to exclude “Zionists” from events or spaces, and some courts have found that these students have legitimate claims.

However, as PEN America has repeatedly said, the ongoing institutionalization of the IHRA definition is the wrong answer to the serious problem of surging antisemitism across the political spectrum. This definition was originally developed as a “non-legally-binding working definition of antisemitism.” But more and more it has become the single arbiter of antisemitism, and what is or is not permissible expression about Israel, in situations that can result in disciplinary or other punitive actions, including legal sanctions. The danger of this codification is even more heightened given the Trump administration’s unprecedented use of concerns about the very real threat of antisemitism as a cudgel to advance a political and ideological agenda against speech and speakers it disfavors and the autonomy of the higher education sector broadly.

There are many more cases like these. Indeed, since the outbreak of the war, Title VI complaints and investigations have become increasingly routine. According to a November 2025 report by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and the Middle East Studies Association, under the Biden administration, at least 65 Title VI investigations into alleged campus antisemitism were launched between October 2023 and January 2025. In that climate of escalating civil rights investigations, anxiety around free speech on campuses grew, as university leaders tried to balance protections for anti-war protesters, concerns with antisemitism, and the chorus of critics scrutinizing their every move.

Whatever tensions were present on campuses before the war, there is little question that these events exacerbated them. In 2025, FIRE reported that nearly 9 in 10 university students who responded to their open-ended survey expressed concerns about censorship, specifically when discussing Israel, Palestine, and/or Gaza. All the while, concerns about students’ understanding of free speech haven’t gone away, either.

American Higher Education at the Start of 2025

This is how America’s colleges and universities entered into 2025: internally divided, financially unstable, politically vulnerable, and increasingly distrusted by large portions of the country. Amid the rising number of Title VI investigations and debates about their own institutional speech, college and university leaders had grown anxious about free speech and about their own policies, with many uncertain of how best to tamp down tensions in their communities, or address concerns about antisemitism.

When Trump was sworn in as the 47th president, the higher education sector was largely unprepared for what was about to happen. Drawing on a set of playbooks developed by conservative activists months or years in advance, the administration moved fast. In his first two weeks in office, Trump signed over 50 executive orders, an immediate demonstration of his theory of the expanded powers of the executive. These were soon followed by a blizzard of new guidance, Dear Colleague letters, legal and regulatory interpretations, and additional executive orders designed to bring the nation’s colleges and universities to heel.

It is in this context – a backdrop of fear, uncertainty, and censorship – that everything else in 2025 played out.

Section III: Model Bills, Reckless Laws, and Internal Contradictions

As noted in Section I, 2025 was a record-breaking year in terms of both the number and the scope of state bills aimed at censoring higher education. Together, these bills cast a web of political and ideological control over higher education, attacking the foundations of free expression from multiple angles. The proliferation of model bills produced by conservative legal activists and think tanks, and designed for easy use by lawmakers in any context or political situation, has enabled this boom. Federal executive orders have also played a part, giving state lawmakers language to incorporate into their legislation, as we will soon discuss. Trump’s list of “divisive concepts” from the tail end of his first administration in 2020 is perhaps the most famous example.

Of course, model bills are not objectionable in and of themselves. Many political causes from across the ideological spectrum offer legislative templates for lawmakers to consider. But when the models pose chronic threats to free expression on campus, and are mixed and matched rapidly, the probability of ending up with laws that are confusing or contradictory, and which create new threats to free speech and academic freedom, is high. Such has been the case with the flurry of state-level bills introduced and passed in 2025. (For more information, see PEN America’s Index of Educational Gag Orders.)

Campus Free Speech Bills

Model state bills targeting campus free speech are not especially new. As PEN America previously discussed in Chasm in the Classroom (2019), a small cottage industry emerged in the 2010s to produce and disseminate bills in response to growing concerns about free speech on campus. This included FIRE’s Campus Free Expression Act, the Campus Free Speech Act from the Goldwater Institute, and the Forming Open and Robust University Minds (FORUM) Act, from the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). Together, these bills claim to offer general prescriptions for free expression on campus, including by mandating free speech education, affirming a commitment to free speech, and abolishing the practice of establishing “free speech zones.” While PEN America supports certain of the provisions in these bills, overall we view them with reservation, particularly because of how some prescribe significant student discipline for vaguely defined infractions, or mandate reporting and legislative oversight in ways that might undermine colleges’ and universities’ autonomy from political interference.

The list of so-called “divisive concepts” originated in this milieu, too, appearing first in the executive order “Combatting Race and Sex Stereotyping” that President Trump introduced in September 2020. Language from that order has since been incorporated into dozens of state bills. More recently, the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 has received attention as providing the overall blueprint for President Trump’s second-term agenda. But the Heritage Foundation is far from the only influential think tank on these matters. The “Freedom from Indoctrination Act,” from the Goldwater Institute and Speech First, formed the basis for at least one law, as well as two other bills that would have been enacted but for last-minute gubernatorial vetoes. The Civics Alliance, launched by the National Association of Scholars in 2021, maintains a “Model Higher Education Code” that includes 24 model bills, laying out a path for everything from how to control accreditation bodies or impose “intellectual diversity” in the classroom to banning donations from the Chinese government. In 2025, Ohio’s SB 1 drew heavily on multiple Civics Alliance bills, as did Iowa lawmakers in at least nine different bills. Meanwhile, visitors to the website of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal in North Carolina will find eight model bills for overhauling higher education. One of them is the End Political Litmus Tests in Education Act, which it co-developed with the Goldwater Institute and is not, as written, a measure PEN America categorizes as educational censorship. But its influence is undeniable: it has found its way, in bits and pieces, into multiple state bills and (virtually in its entirety) into one federal bill introduced last year.

The Spread of Model Bills in 2025

| Model bill | Origin | Number of bills influenced by model legislation | Number of laws enacted influenced by model legislation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EO on Combatting Race and Sex Stereotyping | First Trump Administration, 2020 | 14 bills (proposed in 11 states) | 4 laws (enacted in 4 states) |

Freedom from Indoctrination Act | Goldwater Institute and Speech First, 2023 | 9 bills (proposed in 7 states) | 1 law (enacted in 1 state) |

Abolish DEI Bureaucracies Act | Goldwater Institute and Manhattan Institute, 2023 | 25 bills (proposed in 16 states) | 5 laws (enacted in 5 states) |

Accreditation Autonomy Act | Civics Alliance | 2 bills (proposed in 2 states) | 2 laws (enacted in 2 states) |

Campus Intellectual Diversity Act | National Association of Scholars, Civics Alliance | 1 bill (proposed in 1 state) | 1 laws (enacted in 1 state) |

School of Intellectual Freedom Act | Civics Alliance | 2 bills (proposed in 2 states) | 2 laws (enacted in 2 states) |

Note: This table reflects the influence that a selection of model bills had on 2025 higher education censorship bills tracked in PEN America’s Index of Educational Gag Orders. A bill was considered influenced by model legislation if at least one provision was either directly or substantially copied from the model bill. This may include lists of restricted concepts or activities, even if the proposed bills differ in their mechanisms of censorship. Bills and laws influenced by more than one model bill are reflected in each appropriate entry.

What stands out most about state legislation in 2025 is the dizzying variety of model bills available to state lawmakers interested in regulating higher education, as well as the rapid pace at which these bills continue to be introduced and, in some cases, passed, without due consideration of their consequences. The result is not just bad legislation, but a reckless approach to lawmaking that is chilling the climate for free expression on campus.

Coming Your Way in 2026: A New Model Bill with a Misleading Title

In early December 2025, the Goldwater Institute debuted its latest model bill, “The American Higher Education Restoration Act.” According to its authors, the academic research process is broken. At best, faculty research is trivial; at worst, it is downright un-American. And high-profile journals, which ought to prioritize the pursuit of truth, are making publication decisions on the basis of identity politics and political activism.

To solve this supposed problem, the model bill would have public universities and colleges divide their faculty into three camps. The first would contain all STEM faculty, and the second any faculty members who teach an “Americanism and Western Civilization” course. Both would have fewer teaching responsibilities, and those in the second would also have an expedited path to tenure. The third camp would contain everyone else – generally, faculty appointed to departments in the social sciences, humanities, professional studies, and fine and performing arts. This group would have a heavier teaching load. Should a university seek to hire new faculty in the third group – but not in a STEM field or in a unit teaching Western Civilization – it would first have to seek permission from the governing board, which would scrutinize each posting on an individual basis.

The bill creates additional hurdles for faculty in the third group who seek to use contract time or state resources for their research. Any requests for a reduced teaching load would need approval from a special committee, dominated by politicians and political appointees, to oversee a fund for state-sponsored research of “public value.” Were a university to assign a reduced teaching load to a faculty member in the third group or allocate state funds to support their research without going through that approval process, the state attorney general or any other taxpayer could file for an injunction in court.

One of the stranger provisions of this section is that it would give preference to faculty publishing research in “open-access venues”, thereby discounting many peer-reviewed journals, which are the standard for academic publication.

The goal of it all, according to the Goldwater Institute, is to stop wasting taxpayers’ money on “corrupt academic research.” In reality, it would furnish politicians with one more tool to decide what gets taught, who gets hired, which topics are researched, and who gets tenure. In other words, it is about political and ideological control.

States of Contradiction

As PEN America has documented previously, the rapid spread of these bills has resulted in logical and typographic errors, as well as impossibly vague legislative language. All of this has sown confusion and no small degree of fear among educators, something that 2025’s crop of laws and policies seems destined to exacerbate. Last April, for example, we raised the alarm about Idaho’s SB 1198, a familiar sort of DEI ban that was introduced, passed, and signed into law in just 10 days. Nationwide, the combination of borrowed provisions and limited legislative debate has resulted in legislation and policy that is difficult to implement and, in some cases, susceptible to legal challenge.

For further reading:

Wait, What Just Happened in Idaho? A Wake-Up Call for Higher Ed

Mississippi’s HB 1193, passed into law earlier in 2025, is a good example of this alarming trend. This law requires public K-12 and university faculty to teach that there are only two sexes – male and female. But the law also prohibits educators from offering a class that “increas[es] awareness or understanding of issues related to race, sex, color, gender identity, sexual orientation or national origin.” Together, these provisions are irreconcilable. Professors cannot simultaneously teach students about sex and comply with a law that forbids any formal education that might increase students’ understanding of sex. It is an impossible position, one into which every public university in Mississippi has been plunged. But that’s what happens when lawmakers are more focused on ideological censorship than debating what the various provisions of a bill mean altogether. Mercifully, this provision of the law has been preliminarily enjoined by a federal judge.

Other laws contain provisions so sweeping that their impacts contradict their ostensible purpose. For instance, after allegations from the federal government that Arizona universities were coddling antisemites, lawmakers passed a law banning encampments on campus. However, the language they adopted is so sloppy and extreme that it would seem to prohibit Jewish students from celebrating Sukkot, a holiday during which many Jews construct a temporary structure and sleep in it overnight.

And in Texas, although legislators have spent years discussing the importance of unfettered free speech on campus (and passing a law ostensibly to support it), in 2025 they passed a law so farcically broad that it bans any expressive activity anywhere on campus by anyone between the hours of 10:00pm and 8:00am. What’s more, the law explicitly defines “expressive activity” as expression protected by the First Amendment. This means no after-hours journalism by the student newspaper, no early-morning prayer circle in the campus chapel, no theater rehearsal the night before the big show. The law also bans the playing of drums or the use of sound amplification at any time of day or night during the final two weeks of the semester, so that probably takes care of concerts, marching band practice, or even convocation ceremonies. The ban is total and inflexible, with no exception made for even university-approved events. Thankfully, it has also been enjoined by a federal judge. “The First Amendment,” Judge David Alan Ezra reminded the state in his ruling, “does not have a bedtime of 10:00 p.m.”

Contradictions at the Federal Level

This barrage of state-level legislation has been amplified by the deluge of executive orders (EOs) and other policies coming from the Trump administration. Starting on day one, January 20, when he signed a stunning 26 EOs, the aim has been to “flood the zone” and overwhelm the opposition. In 2025, Trump signed 225 EOs, a number one might expect over the course of an entire presidential term (in Trump’s own first term, he issued just 220). While a large number of these EO’s have already been challenged in the courts, their impact persists.

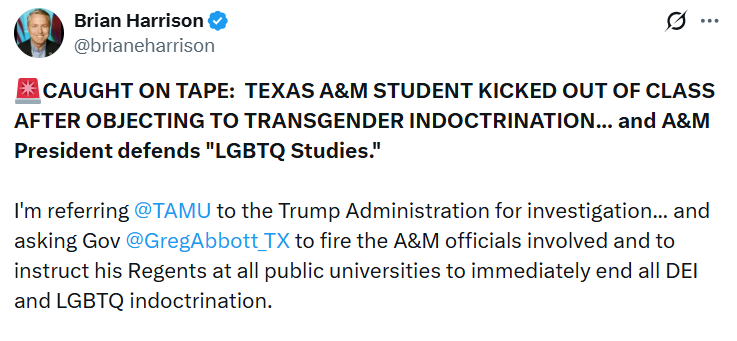

According to NAICU (the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities), 19 of the EOs so far take aim at higher education. Some do so head-on, by undermining DEI programming and accreditation standards, wiping out an established merit-based system of grant making, and banning trans women from participating in the women’s divisions of intercollegiate sports. But there are others that, because of the breadth of their framing and mistaken assumptions about their scope, have also impacted higher education. For example, one of the first EO’s issued on January 20 was Executive Order 14168, “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government.” As that name suggests, the focus of this EO is on the federal government. It does not apply to universities, let alone to classroom teaching. Yet it was precisely this EO that a Texas A&M student cited when she disrupted a class discussion because it referenced gender diversity in literature. That complaint subsequently led to the professor’s dismissal.

Another example of how the federal government is exerting undue authority over higher education can be found in the Dear Colleague letter issued by the Office for Civil Rights on February 14, and the subsequent FAQ sheet issued on February 28. This letter put all colleges and universities on notice that the continuation of DEI programming could jeopardize their federal funding, citing the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (SFFA) as precedent. But as PEN America made clear in our statement condemning this guidance, “This declaration has no basis in law and is an affront to the freedom of speech and ideas in educational settings. It represents yet another twisting of civil rights law in an effort to demand ideological conformity by schools and universities and to do away with critical inquiry about race and identity.” And we were right: in August, a federal court vacated the letter. But in the meantime, many colleges and universities rushed to comply with the federal government’s letter, shutting down programs and killing initiatives not easily resurrected. The damage was done.

Catch-22: Conflicting Rules from the Federal Administration

There is one additional example of the federal administration’s efforts to change the rules for higher education that deserves close consideration, since it illustrates how the torrent of laws, executive orders, and legal threats from state and federal actors can combine and contradict one another in unexpected ways.

In late July, the Department of Justice released a “Guidance for Recipients of Federal Funding Regarding Unlawful Discrimination.” Across nine pages and dozens of examples, it attempts to lay out the sorts of discriminatory practices that can cost schools, universities, and other organizations their access to federal funds. For instance, it asserts that a university may not establish or allocate resources to support a “safe space” for students of a particular religion or national origin, as this would constitute unlawful “segregation,” even if “access is technically open to all.” Nor may universities engage in “preferential hiring or promotion practices,” for instance by trying to recruit students from specific institutions or parts of the country that “correlate with, replicate, or are used as substitutes for” a particular race or ethnicity. So no more sending recruiters to predominately Black high schools in order to channel Black students into the freshman class. The federal government will not tolerate that sort of thing anymore.

Except when it does. In fact, the very next day after issuing its guidance to universities, the Department of Justice announced that it had reached a settlement with Brown University over alleged antisemitism and other discriminatory practices. Among the terms of that settlement: Brown will take actions “to support a thriving Jewish community,” perform “outreach to Jewish day school students to provide information about applying to Brown,” provide “resources for religiously observant Jewish community members,” offer “support for enhanced security at the Brown-RISD Hillel,” and muster university resources to “celebrate 130 years of Jewish life at Brown in the 2025-2026 academic year.”