For years, András Pethő believed that the United States was different from his home country of Hungary. Here, it seemed as though a steadfast belief in the freedom of the press was “in the DNA” of the owners of media companies.

But following major settlements by ABC News and Paramount, Pethő learned that wasn’t the case. Instead, he said, he realized that it’s easy for anyone to defend press freedom when it’s not under threat.

Weaponizing the law to silence journalists, turning reporters into public enemies, and cutting off access to information are all tactics familiar to four journalists — Pethő, M. Gessen, Ramón Zamora, and Sevgi Akarçeşme — who gathered at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY to discuss their experiences witnessing the rise of global authoritarian regimes and the warning signs they’re watching emerge in the United States.

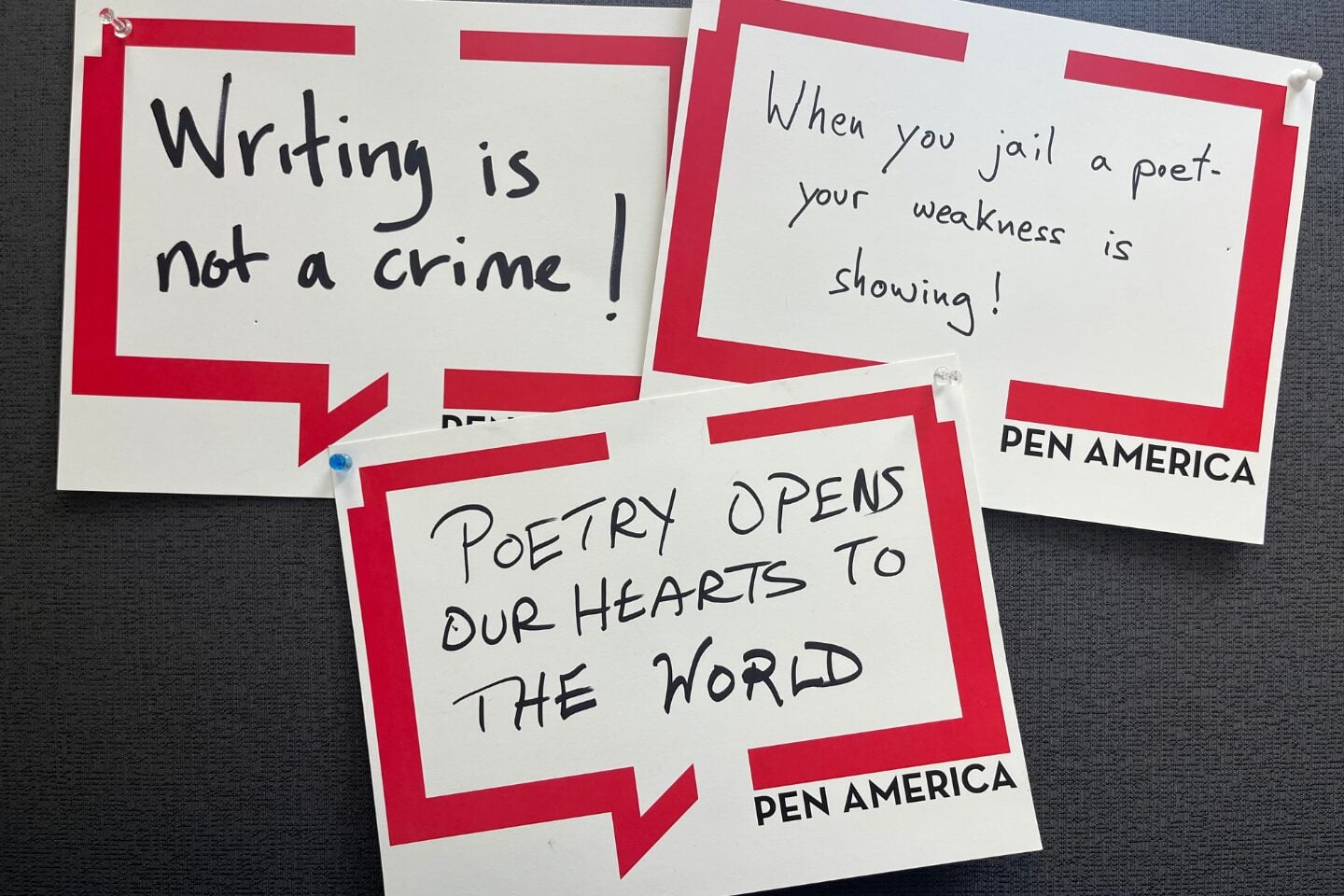

The event marked the launch of Kronika, an expansion of PEN America and Bard College’s Russian Independent Media Archive (RIMA) that aims to protect endangered journalism across the globe from censorship.

During the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion into Ukraine, Gessen, now a New York Times opinions columnist, was in Moscow reporting on the operations of TV Rain, the country’s last independent TV channel. One night, its journalists were left with no choice but to flee the station’s offices for their safety. Gessen knew many of them would never return to the offices — or even Moscow — and, in the days that followed, began asking them where TV Rain’s archive was located.

“Nobody knew exactly the answer to that question. A lot of people thought the archive was online, but of course we only think that the internet is forever,” Gessen said. “The internet is only forever as long as somebody is paying to maintain it and as long as nobody’s trying to take it down.”

Gessen worried that without an archive of independent reporting, both Russian journalists and the public would be in trouble. Everyone would grow to have “completely different ideas of what came before,” and their ability to communicate about the past would deteriorate. So Gessen and PEN America Trustee Peter Barbey came up with a solution: a media archive that would safeguard TV Rain and other Russian-language outlets against state censorship. PEN America and Bard College joined forces later in 2022 to bring the idea to fruition with Barbey’s support, and since then, RIMA has preserved the work of almost 150 outlets.

“With Kronika, we’re opening our tools and partnerships beyond Russia — to any newsroom or civic initiative confronting erasure — so facts remain verifiable, stories remain findable, and history remains public,” said Ilia Venyavkin, Kronika’s director of programs.

Liesl Gerntholtz, managing director of the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center, moderated the panel of journalists, titled “We’ve Seen This Before: Lessons from Exile on Recognizing Authoritarianism.”

Zamora, a former product manager at the Guatemalan outlet elPeriódico who collaborated with RIMA and Bard College to launch the Central America Independent Media Archive, said he’s seen political leaders in both Guatemala and the United States use the law to silence journalists. His father, José Rubén Zamora, has been jailed in Guatemala for more than three years for his reporting and has been targeted by more than 200 lawsuits in that time. As Zamora watches lawsuits against journalists grow more common here, he can’t help but think about the chilling effect they’ll have on newsrooms nationwide.

Pethő, the co-founder of an independent news outlet in Hungary, recalled that after Prime Minister Viktor Orbán began to crack down on the media, the owners of the newspaper where he worked at the time tried to dissuade him and his colleagues from pursuing a slew of stories about Orbán. When the editor-in-chief refused to comply, the owners forced him out of his job. Pethő and many of the site’s other journalists resigned shortly thereafter, and later Pethő went on to co-found his own investigative reporting outlet, Direkt36.

Now, watching media owners in the United States cave to political pressure by settling meritless lawsuits, he knows exactly what they’re surrendering. “If you let someone else, especially people in power, tell you what kind of questions you can ask, [to] whom you can ask those questions, what kind of stories you want to pursue, then that’s the end of it,” he said. “You lose your credibility, and that’s the only thing you have in this business.”

Akarçeşme, a journalist in exile from Turkey, said that alongside criminalizing journalists, authoritarian leaders do all they can to turn them into a public enemy. She explained how the president of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, vilified the media following coverage of an explosive corruption scandal. “In every single rally, in every single media appearance, he repeated the same rhetoric over and over and over again,” she said. “After a certain point, you just didn’t want to hear his voice. It’s happening to all of us nowadays in the United States.”

Gessen added that journalists have also been cut off from access to information, citing the Pentagon’s new restrictive reporting rules. In fact, Gessen said that they could identify just one tactic to suppress the media that hasn’t yet been employed in the United States: pressuring advertisers to boycott outlets. “But it’s so easy, and it’s so effective, and it’s so going to happen,” they said.

Toward the end of the evening, Gerntholtz asked the panelists to reflect on how American journalists and society at large should respond to the signs of authoritarian drift they discussed.

Akarçeşme stressed the importance of acting early, stating that resistance doesn’t work after a certain point. In Turkey, reporters can now only “play journalist,” she said; anyone who produces truthful, investigative reporting risks imprisonment or exile.

She specifically urged American journalists to call out verbal abuse, referencing recent incidents where President Donald Trump called one reporter “piggy” and another a “terrible” person and reporter. “I’m so shocked and disappointed that American colleagues are not speaking up. They’re not protesting. They don’t say, ‘We are leaving this room,’” she said.

Zamora, too, said that journalists need to stand by one another. The night his father was detained on charges of money laundering, blackmail, and influence peddling, authorities also took over the newspaper’s printing press — but three other newspapers called Zamora and offered to print the coming edition free of charge. And during one of Guatemala’s elections, seven of the top outlets in the country joined together to provide fact-checking services to the public.

“That was really powerful,” he said. “The only thing that can actually work is more journalism. Attacks against journalism are fought back with more journalism.”