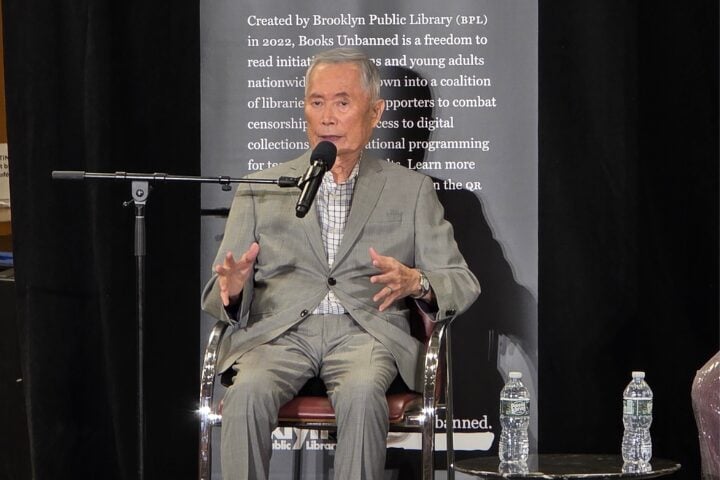

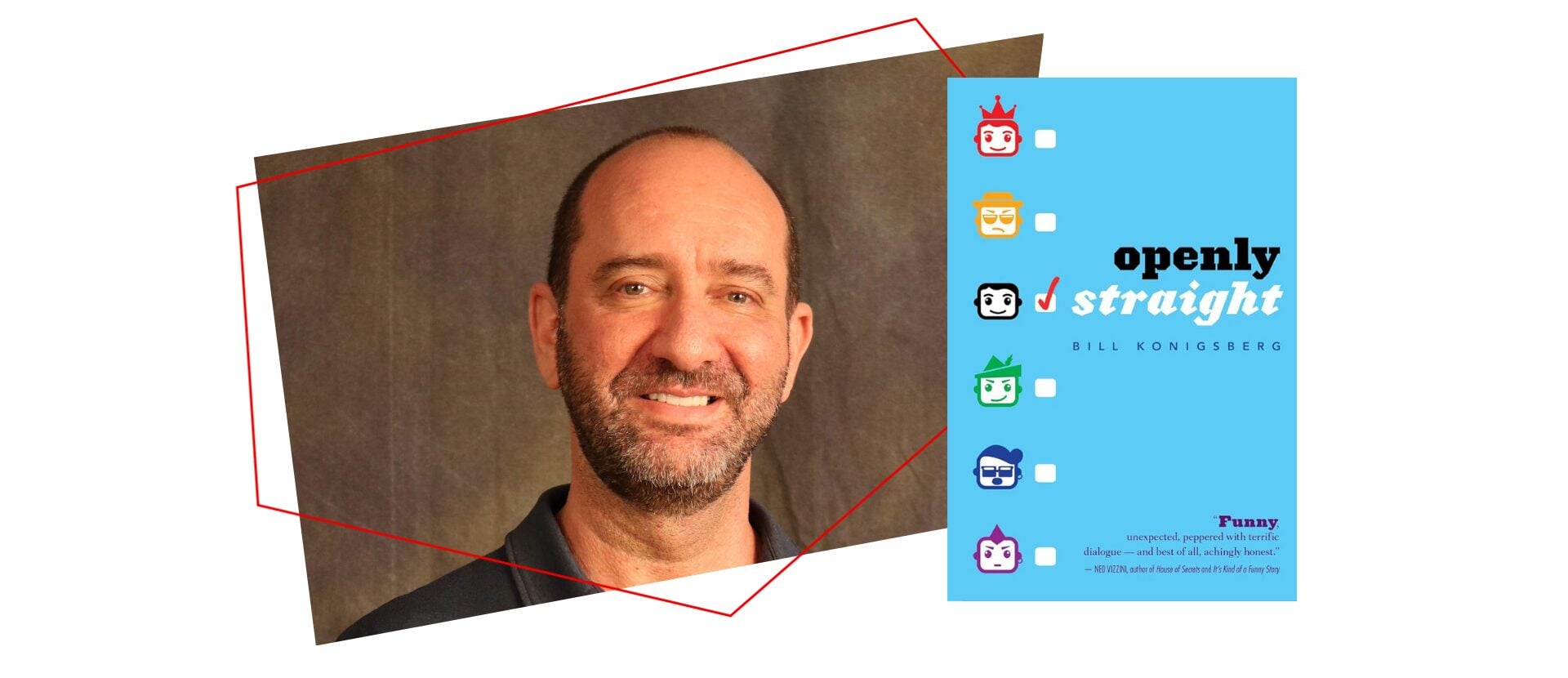

Award-winning novelist Bill Konigsberg is fed up with book bans.

“I think of myself, and I think of a lot of people who write young adult books, as benevolent souls who are trying to help,” he said, “and I think that it’s hard when you try to help and you’re treated as the problem.”

Of the seven young adult books Konigsberg has written, five have been banned repeatedly, according to PEN America’s indexes of banned books. They rarely narrate sex explicitly, but they prominently feature queer characters and, at times, they imply the occurrence of sex or sexual violence.

In this interview, Konigsberg describes the challenges he faced as a young queer person and explains how he’s dedicated his career to helping today’s queer teenagers handle similar challenges. It’s a point he thinks some book banners would recognize, were they actually to read his books.

Interested in hearing more insights from experts about the merits of including sexual content in young adult literature? Check out the other three installments of this series, in which we speak with Andrew Karre, Executive Editor at Penguin Random House’s Dutton Books for Young Readers, and critically acclaimed authors Malinda Lo and Elana K. Arnold.

Queer literature offers solace to queer readers.

Though he was born and raised in New York City, Konigsberg didn’t know any other queer people growing up. He was bullied frequently, and he had nowhere to turn for resources. Most of the time, he felt “totally alone.” Not much helped — but literature did.

Konigsberg still remembers the first queer young adult book he got his hands on: All-American Boy, a 1999 memoir in which Scott Peck recounts growing up as a young, gay man in the Christian South. “I was about 19 at the time, maybe 18, and it was hugely valuable to me,” Konigsberg said. The book taught him that there were other young queer people struggling to accept themselves and be accepted by others, which provided him with a sense of companionship and relief.

Since he began his career as an author, Konigsberg has tried to write books that could do the same for teenagers today. And through his many correspondences with young readers, he’s learned that he’s succeeded in that mission. In one interaction Konigsberg recalls especially fondly, a teenage reader disclosed that he kept Konigsberg’s books under his bed and thought of them as his “secret boyfriend.” “When I read these things, I feel like somebody understands me,” the reader told Kongisberg.

The reader, now in his 20s, is happily married to his first (real) boyfriend. “It was absolutely wonderful to first hear from him when he was 16…and it’s lovely to see him now succeeding,” Konigsberg said.

YA novels can approach sexual content in a variety of ways, but steering clear of it entirely isn’t one of them.

“My goal from the very beginning has been to tackle the teen years authentically,” Konigsberg said. “I think teen readers can sniff out bullshit really well, and to not write about sex and sexuality when writing about teens seems strange to me.”

Still, Konigsberg’s instinct has never been to write descriptive sex scenes. He instead opts for coded language in novels like Openly Straight and its sequel, Honestly Ben, which trace a budding romance between two queer high schoolers. In one of the novels, a character remarks that having sex feels like being “protected” — and so when Konigsberg employs that same verb later in a scene with his two protagonists, it’s clear that they had sex.

Fans often email him with questions about scenes like that one, eager to learn more about what specifically transpired between the characters. “And that’s perfect to me,” Konigsberg said. Readers are free to use their imagination as much or as little as they’d like, but the choice will remain in their hands.

Though other writers of young adult fiction include more explicit descriptions of sexual encounters, it’s still wrongheaded to remove those books from shelves, Konigsberg added. “If this was about keeping pornography out of school libraries, I could get behind that. … But there is no pornography in school libraries, because librarians’ jobs are to keep books appropriate for their young readers.”

Unpleasant sexual experiences and sexual assault deserve to be depicted in literature, too.

Destination Unknown is one of Konigsberg’s only novels that hasn’t been banned. Ironically, he would argue it’s also the only one that depicts sex. In the novel, set in New York City during the 1980s, two queer characters have sex near abandoned train tracks. Though it’s a fairly unremarkable encounter for the more experienced of the two characters, it’s unfamiliar and unpleasant for the other.

The novel is semi-autobiographical; specifically, the more sexually experienced character is inspired by Konigsberg’s younger self. “He was wild and I was wild,” he said.

Still, Konigsberg emphasized that many of his early sexual experiences were negative. Rejected by his peers, he found his way into queer adult circles when he was just a teenager. “I was too young for that,” he said. “I don’t have memories of things being sexy. I have memories of things being traumatic.”

Konigsberg tackles loneliness and fear, which he felt frequently as a teen, in Destination Unknown as well as in The Music of What Happens to support readers grappling with the same emotions. In The Music of What Happens, one of the protagonists is raped by an older boy, though the scene narrates his dissociation from the assault rather than the assault itself.

After the novel was challenged in California, Konigsberg received vitriolic emails claiming he had “pedophile vibes” and asking if he was friends with Jeffrey Epstein. “And as somebody who was actually groomed as a teenager and has lived to tell, that was extremely triggering for me,” he said.

But he also received many emails from readers saying that they had been sexually assaulted and that they found comfort in The Music of What Happens. “I included the date rape for that reason: because I knew that that character and what he went through is something a lot of people have gone through,” he said. “I wanted somebody to read that and feel less alone.”