Toward New Symbols and Platforms

By Kyle Dacuyan

At the very end of August, I was in Charlotte and Durham, North Carolina, to meet some PEN America Members and partners who we will hopefully be working with through our Press Freedom Incentive Fund—a new resource to facilitate programs and mobilize local communities around press freedom advocacy. A few weeks prior, activists in Durham had tied a yellow rope around the courthouse’s Confederate statue and, with seemingly little effort, pulled the figure from off its granite pedestal. There was a lot of conversation about the statue while I was there. There has been a lot of conversation about statues since.

Statues and symbols—and names, and holidays, and other honorifics. About a week ago, the statue of Christopher Columbus in Central Park was found with its hands painted red and a message in white splashed across the plinth: “Hate Will Not Be Tolerated. #SOMETHINGSCOMING.” Near my hometown in Virginia, a community vote was recently held to rename J.E.B. Stuart High School, with the most popular selections heading to the superintendent and soon to the school board. Suggestions from the community included Beyoncé Knowles (7 votes); Triggered Snowflake (18); and Schooly McSchoolface (44)—but also Barbara Rose Johns (737), a student who led an equal education strike in 1951; and Thurgood Marshall (763), the first black Supreme Court Justice. Coming out at the top with 917 votes, however, was the static choice: “Stuart.”

The ways we have carried forward certain men as symbols of heritage have historically and undeniably downplayed their own perpetrations of violence—Columbus’s role in indigenous genocide; Stuart’s role as a Confederate general in defending slavery as an institution. Then again, we might also say the same of the many Founding Fathers who were themselves slaveholders. We might say that many forms and subjects of valor in our country disguise the realities of the violence on which our country was founded, and that this sanitization of history helps perpetuate structures of oppression. Interrogating our national symbols is necessary to disrupting and dismantling power, but so is erecting new symbols and stories, or rather amplifying and holding space for stories that have long been marginalized—choosing to recognize “Indigenous Peoples’ Day,” for example, as opposed to “Columbus Day.”

When I came to North Carolina, I was thinking about that recently toppled statue. When I left, I left with the bracing knowledge that many advocates, groups, and publications are also doing critical work to advance underheard narratives. Free Press, for example, convened a well-attended, justice-centered forum that engaged community members with local journalists to discuss issues of representation, inequity, and access. The discussion was wide-ranging—from the broadband deserts which affect information access, to how journalists can meet more diverse needs in the media development process, to how reporters and advocacy leaders might mobilize around specific local issues.

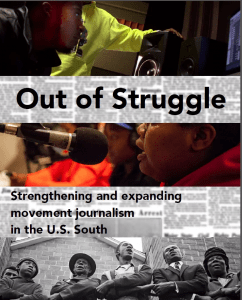

I also met with editors from Scalawag, a publication focused on the “many Souths,” which aims to “amplify voices of activists, artists, and writers to reckon with Southern realities as they are, rather than as they seem to be.” One of their editors, Rachel Garringer, founded and directs Country Queers, an oral history project composed of stories from LGBTQIA individuals in rural and small town communities. Another editor, Anna Simonton, recently led a comprehensive report from Project South on using movement journalism to meet the information needs of vulnerable communities.

I also met with editors from Scalawag, a publication focused on the “many Souths,” which aims to “amplify voices of activists, artists, and writers to reckon with Southern realities as they are, rather than as they seem to be.” One of their editors, Rachel Garringer, founded and directs Country Queers, an oral history project composed of stories from LGBTQIA individuals in rural and small town communities. Another editor, Anna Simonton, recently led a comprehensive report from Project South on using movement journalism to meet the information needs of vulnerable communities.

I came back from North Carolina to September in New York, a busy and joyfully exhausting time of year in the city. I do have to say: I’ve been frustrated in the past to live in such a diverse place and still sometimes experience really homogenous programming. More than half of New York City is nonwhite. Yet I see many events happening with almost entirely (too often, entirely) white lineups, casts, and speakers. This is irresponsible. Who we give a cultural platform to is not discontinuous with who we give a symbol, or a statue, or a holiday. And so I’ve made a commitment to not attending or supporting programs where this is the case. The good news is that there are many curators out there producing thoughtful, singular, carefully representative events.

Jason Koo of Brooklyn Poets hosted a kick-off to their fall season with a reading featuring a trio of electric new books by Danez Smith, Emily Skillings, and Nicole Sealey, who has selections from a cento recently featured in the PEN Poetry Series. It was an evening of poets going everywhere, leaping in differently associative, staggering ways. Later that weekend, I headed to DTUT on the Upper East Side for another favorite reading series, Dead Rabbits, with poems from Robert Balun and Brionne Janae and prose from NJ Campbell, T Kira Madden, Kyle Lucia Wu, and Noy Holland. I always try to catch Dead Rabbits because the hosts, Devin Kelly and Katie Rainey, bring together a thrilling mix of emerging and established writers—but also because they write the most artful, deeply felt introductions for each of their readers.

This year, September also brought back-to-back weekends of Slice Literary Conference and Brooklyn Book Festival events. At Slice, Alison Kinney moderated a rich discussion with Moustafa Bayoumi, Garnette Cadogan, Morgan Jerkins, Kelly Mays McDonald, and Joel Whitney on writing essays in the age of Trump—touching on the considerations of one’s subjectivity within a broader cultural context, as well as the merits of a steadier vs. more reactionary writing practice. Mary Gannon of the Academy of American Poets also moderated an excellent conversation between Hafizah Geter, Ricardo Alberto Maldonado, Jenny Xie, and Javier Zamora on engaging poetry with memory, specifically across generations, and around experiences of displacement and resettlement.

At the Brooklyn Book Festival, PEN America’s Clarisse Rosaz Shariyf moderated a panel with Peter Kimani, Naivo, and Avinuo Kire on the legacies and tolls of European imperialism—and our executive director, Suzanne Nossel, served on a panel with Jelani Cobb and Michelle Goldberg, moderated by Stig Abell of the TLS, to discuss campus free speech. The programming throughout both Slice and the Brooklyn Book Festival challenged attendees to reconsider our traditional power structures and assumptions about equity. As Jelani Cobb shared, “When you have a hierarchal society, even civil liberties can be used to reinforce the hierarchy. Even democratic principles can be used undemocratically.”

But by far the most surprising, honestly inspiring event I’ve attended in months is one I went to alone this past weekend—Queer Abstract, a monthly performance and reading series hosted by Shannon Matesky at Starr Bar. Queer Abstract brings together eight to ten artists each month, all queer and trans people of color, and this month’s lineup included Trent Love, Justin Allen, Adam Setton, Aviva Jaye, Riki Stevens, Willy Luperon, Shannell Edwards, and Níke Kadri. The theme was “What Brings You Joy?”

So often when I go to an event with a homogenous lineup, the readers seem engaged in a competition of irony and disaffection, of proving who can be the most “over it.” Not at Queer Abstract. The readings and performances were tender, private, provocative, and raucous. Over the last nine months, Shannon Matesky has put together evenings with over 90 QTPOC artists and writers. “Show up for your people,” she said, opening the evening. “And don’t tell us we aren’t here.”