The PEN Ten: An Interview with Connor Towne O’Neill

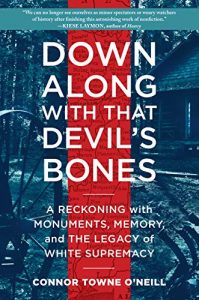

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Connor Towne O’Neill, author of Down Along with That Devil’s Bones (Algonquin, 2020).

Photo by Joel Brouwer

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

The first line of Charlotte’s Web was, if memory serves, the first line of literature I knew by heart. And it’s a tremendous first line. “Where’s Papa going with that axe?” Danger! Image! Drama! Dialogue! I still return to that book often—it’s beautiful, full of tenderness and humor and wisdom about friendship and grief and loss. Actually, one of the first things my parents said to me after reading my book was to appreciate the nod I made to the litany delivered by Templeton the Rat after his night out at the county fair.

2. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Lillian Smith’s Killers of the Dream. Smith was a white southerner writing in the 1940s with searing insight about the consequences of forging a society and an identity around the lie of white supremacy. It is devastating and necessary, and sadly, just as urgent today as it was 70 years ago. Every white American should read it.

“Stories allow us to understand ourselves in the context of time. They are a way of marking change, of identifying pattens within that change—which allow us to make sense of and reflect on that change. We’re story-finding creatures as much as we are storytelling creatures.”

3. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

The last book I read was Eddie S. Glaude Jr.’s Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and its Urgent Lessons for Our Own. I love the hybrid approach Glaude takes—part literary study, part commentary, part biography. He’s able to telescope the present into the past and vice-versa. After reading it, I felt better equipped to grapple with the biggest questions facing the country today. Next up for me is Eric Nusbaum’s Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught In Between. It’s a book that excavates stories of the LA neighborhoods that were destroyed to build Dodger Stadium.

4. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Writing and identity are all bound up in each other for me. Actually, I think that writing this book forced me to come to terms with my identity as a white American in a deeper and more honest way, which then shaped how I rewrote and revised the book. This book was a daunting reporting project. There were so many people to interview, archives to visit, battlefields to trudge through, and monuments to see. And so, starting out, I didn’t think there would be much room for me and—maybe more damningly—that there didn’t need to be. But the more I dug into the history of Forrest and his monuments, the more I started to trace that history into the present. In other words, I began to understand the consequences of his story. I realized that all of this, past and present, turned on questions of whiteness. Which meant that I was implicated, too.

I’ve been prompted to ask questions about race that I’d never thought to ask before. So much about American life encourages white people to take our whiteness for granted. It’s insidious that way. White people don’t want to talk about whiteness, don’t want to see it, don’t want to think about what it means, how it was invented, and how it is enforced. But as I charted the battles over Forrest’s monuments, I would come to see how whiteness operated—and how that lie of white supremacy pins us into systems of violence and inequity. I had to reckon with the fact that American history is terrifying and painful. That America’s present is terrifying and painful, too. I wrote this book to try to better understand my place in it. I had to write this book to understand my place in it. To tell the story of Forrest and his monuments, I had to revise the story I told about myself. And I think that process of revision is part of the writer’s identity—using writing to deepen our sense of ourselves and our world. Writing is revising. It’s the painful work of returning again and again to the page to work over a line, to rethink the structure of the story, or to resituate our place in it.

5. What advice do you have for young writers?

Write. Write often and write freely. It took me so long to overcome the anxiety I felt about writing. I was scared of how vulnerable you make yourself when you write. And so, I avoided it at all costs. And my thinking suffered for it. So did my understanding of myself and my understanding of the people around me. And, frankly, the quality of my writing suffered too, which only compounded the issue. So, write. Don’t get hung up on it. Get it out; get it down.

“The central question of [the Civil War] was whether a settler, slave society could transform itself into a multiracial democracy. More than 150 years later, we’re still struggling to resolve that tension, and so, we are still fighting over the memory—the meaning of the war.”

6. Why do you think people need stories?

Stories allow us to understand ourselves in the context of time. They are a way of marking change, of identifying pattens within that change—which allow us to make sense of and reflect on that change. We’re story-finding creatures as much as we are storytelling creatures. We need stories, and we find stories everywhere. And we always need new stories, new patterns, new questions, and new ways of answering them.

7. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

Alicia Kennedy. She writes about food in a way that shows how entangled it is with race, colonialism, environment, economy, pleasure, and pain. She’s a tremendously insightful and engaging writer. She has a newsletter and, I think, is working on a book.

8. Your book, Down Along with That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy, explores the battle over monuments by examining those erected for Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, who became the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. One of the two epigraphs for the book comes from Viet Thanh Nguyen and reads, “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” How does examining Forrest and his legacy exemplify this epigraph?

8. Your book, Down Along with That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy, explores the battle over monuments by examining those erected for Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, who became the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. One of the two epigraphs for the book comes from Viet Thanh Nguyen and reads, “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” How does examining Forrest and his legacy exemplify this epigraph?

So, the first fight is, of course, the Civil War itself. The second fight is about the consequence of the war, of what that war would mean for the country moving forward. As I see it, the central question of that war was whether a settler, slave society could transform itself into a multiracial democracy. More than 150 years later, we’re still struggling to resolve that tension, and so, we are still fighting over the memory—the meaning of the war.

So, it matters how we remember a man whose early life moved west with the Trail of Tears. It matters how we remember a man who became, by some counts, one of the richest men in the south by working as a slave trader in Memphis, the inland capitol of the slave trade. Who used that fortune to equip his own regiment in the war fought to defend that system. Who, after the war, undermined the efforts of Reconstruction to achieve that multiracial democracy by serving as the first grand wizard of the Klan. And who, in his last years, operated a convict leasing plantation—a system known as “slavery by another name.” That’s the man who we’ve enshrined into so many public spaces. So, by looking at Forrest’s memory, I came to understand how we still struggle to come to grips with the consequences of our past. We cannot simultaneously honor a man like that and believe we have any shot at resolving the central tension of the country. We’re still fighting that second war.

“We need enough of us to come to a common understanding of our past, one that squares up to the violence and inequity inflicted by the lie of white supremacy. We need to understand how the inequities in our society. . . are the consequences of that lie. If we can come to that common understanding of the past, we might build the consensus necessary to enact policies that can address those inequities in our present.”

9. What did your creative process look like while working on this book? How did you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I tried to write every morning. Those first hours of the day—and let’s be honest, the caffeine hit from the first cup of coffee—are precious, so I tried to wring as much writing out of those hours as I could. If I wasn’t teaching that day, I’d research and report in the afternoon. Then, I’d walk the dog in the late afternoon to brush the cobwebs and then read in the evening. It’s amazing how important that time was. On walks, issues I’d been wrestling with or ideas I’d been struggling to express would suddenly make sense. You set things on the burner and let them stew during the day. It can take a while for an idea to set. You’ve got to give yourself time away from it. And it’s amazing how, often as not, if the writing loses steam, it’s down to the fact that I’m not reading enough. Reading is a way of keeping logs on the fire. So much writing work happens away from the blinking cursor.

10. Near the end of the book, the question of how we tear down “thought monuments” is raised. As you write, “A symbol is gone; the system remains.” What do you think is necessary outside of the removal of physical, symbolic representations of America’s history? In what ways do we still need to reckon with the past, to understand our present, and create a better future?

We need enough of us to come to a common understanding of our past, one that squares up to the violence and inequity inflicted by the lie of white supremacy. We need to understand how the inequities in our society—from the racial wealth gap to unequal schools to access to healthcare—are the consequences of that lie. If we can come to that common understanding of the past, we might build the consensus necessary to enact policies that can address those inequities in our present. And so, protests over things like Confederate monuments—these conspicuous symbols of that inequity—can help bring more people into the larger work of dismantling the systems that those symbols represent.

Connor Towne O’Neill works as a producer on the NPR podcast “White Lies.” Originally from Lancaster, PA, he lives in Auburn, AL, where he teaches at Auburn University and with the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project. His writing has appeared in New York Magazine, Vulture, Slate, Red Bull Music Academy, and The Village Voice.