The PEN Pod: Remembering Terrence McNally with Jesse Green

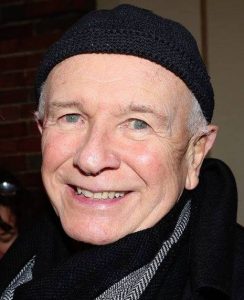

Terrence McNally, who died at age 81, leaves behind a legacy as a playwright who Photo by Wikimedia Commons

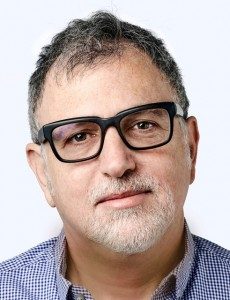

In today’s PEN Pod episode, Jesse Green, co-chief theater critic at The New York Times, joined us in remembering playwright Terrence McNally, who died yesterday at age 81 and was among the first in the literary community to succumb to complications from coronavirus. We spoke with Jesse about the impact of McNally’s legacy, how his work reckoned with gay life in particular, and how theater can change minds. Listen below for our full conversation (our interview with Jesse begins after the five-minute mark).

Among Terrence McNally’s many works are renowned plays like Kiss of the Spider Woman, Ragtime, Master Class, etc. How do you define the work of Terrence McNally?

McNally’s work was generally about outsiders, people trying to get into something that they felt they had been excluded from. They were often gay, but when they were gay, they were also stand-ins for the outsiderness everyone feels, maybe even especially right now, when the world is not the world that you thought it would be. So, for example, in Ragtime, you’ve got groups of African Americans and immigrants trying to find their way in a new country. In Spider Woman, you’ve got a political prisoner and a prisoner of homophobia sharing a jail cell. And in Master Class, you’ve got Maria Callas, who, as a young woman, was told she was too ugly and too unmusical ever to be seen on an opera stage. He championed people like that, although I should say never unequivocally.

“He didn’t just dramatize the change that I’m talking about; he helped to make it stick by sharing it with a very mainstream audience. He wasn’t writing for a niche audience. He was acculturating and teaching a commercial Broadway audience.”

Jesse Green, Co-Chief Theater Critic, The New York Times

You write in his obituary that his first Broadway production was a bomb called And Things That Go Bump in the Night, but it featured a romance between two men. How did McNally’s work reckon with gay life in particular?

I should just add, by the way, I didn’t put it into the obit, but those two men—one was, at that time, that new kicky thing called a bisexual, and the other was what they then called a cross-dresser. So even McNally was at that time partaking in some of the “aren’t they crazy” kind of normalizing effect that some plays did in their treatment of gay characters. But over the longer arc of his career, his treatment of gayness followed the arc of the times: from the closet, to liberation, to disaster, to marriage and parenthood. In one of his last plays, called Mothers and Sons, a gay man has married and they have a five-year-old son together. So, again, this was not done unequivocally. In that play, Mothers and Sons, the mother—who was played by Tyne Daly by the way—is a furious old homophobe, but she’s not unlovable. And the young gay dad is totally right on the politics, but he’s a bit of a pill. The other thing to say, though, is that he didn’t just dramatize the change that I’m talking about; he helped to make it stick by sharing it with a very mainstream audience. He wasn’t writing for a niche audience. He was acculturating and teaching a commercial Broadway audience. So if his plays sometimes seemed ingratiating, that was why. It was on purpose.

You also write about one of the first shows McNally saw, which was the musical Annie Get Your Gun. What impression did that have on him and his career?

I think the impression that it had was to make him realize that theater could change things, could change minds. Annie Get Your Gun is not a profound piece of work politically, but it still literally rewired his own brain so that decades later, the scenes he saw—the way Ethel Merman turned her hand or warbled a note—was as fresh to him as when those things were first encoded in his neurons. So, I think it taught him that he could do something in the theater that few people have an opportunity to do, which is to change people’s minds forever.

“I think it taught him that he could do something in the theater that few people have an opportunity to do, which is to change people’s minds forever.”

How do you think Terrence McNally will be remembered by the theater and literary community here in New York and globally?

Just speaking personally, I met him a number of times, I interviewed him now and then, and I knew his husband Tom, so one thing I think is that people who knew him or knew of him in the theater will remember him as an incredibly generous and lovely guy, who actually lived the change he was writing about. He wasn’t just, you know, reading a history book and trying to make it seem real; he had been through it. His parents were totally unaccepting of his relationships. They didn’t want to hear about it. And yet, after years of problematic relationships—including famously, for five years with Edward Albee—he married a wonderful man who eventually became the producer of his plays. So, another thing I think he’ll be remembered as, aside from this incredible body of work—35 plays (maybe 36), 10 musicals, 4 screenplays for opera librettos—will be an example of a way to live as an artist, in kindness.

Send a message to The PEN Pod

We’d like to know what books you’re reading and how you’re staying connected in the literary community. Click here to leave a voicemail for us. Your message could end up on a future episode of this podcast!