Steeped in Specificity

The following transcript is adapted from a conversation at the 2017 PEN World Voices Festival. It will appear printed in the forthcoming issue of PEN America: A Journal for Writers and Readers, out in one week. Issue 21: Mythologies considers stories that have been transmitted to us by teachers, writers, parents, politicians, and pop stars—and the mechanisms of their transmittal. In Issue 21, Natalie Diaz takes us to the banks of the Colorado River, Rodrigo Hasbún seeks out fabled Incan cities, T Kira Madden goes to the Olympics, and Carmen Maria Machado assembles a pantheon of feminist saints. Copies of PEN America: A Journal for Writers and Readers can be purchased online, or received as a benefit of PEN America membership.

The following transcript is adapted from a conversation at the 2017 PEN World Voices Festival. It will appear printed in the forthcoming issue of PEN America: A Journal for Writers and Readers, out in one week. Issue 21: Mythologies considers stories that have been transmitted to us by teachers, writers, parents, politicians, and pop stars—and the mechanisms of their transmittal. In Issue 21, Natalie Diaz takes us to the banks of the Colorado River, Rodrigo Hasbún seeks out fabled Incan cities, T Kira Madden goes to the Olympics, and Carmen Maria Machado assembles a pantheon of feminist saints. Copies of PEN America: A Journal for Writers and Readers can be purchased online, or received as a benefit of PEN America membership.

___________________

CHRIS JACKSON: It is such a beautiful night, there’s so much love in the room. So I’m going to bring a stinking corpse onto the stage: the presidential election. Immediately after the election, both of you wrote pieces that got passed around. You’re both basically African immigrants. I’m curious about how much of your reaction was informed by the cultures you grew up in.

CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE: I don’t think of myself as an immigrant in the United States, I think of myself as a Nigerian who lives in America part of the year. My sensibility is largely shaped by Nigeria. I didn’t come to the U.S. until I was nineteen. I grew up in a military dictatorship, and growing up in that political space, I remember being a child and my parents and their friends talking in our living room. The doors were closed and my parents were whispering because they were talking about the government. I remember thinking, Why are they whispering? And that memory has stayed in my mind as an example of what it means to live in a dictatorship. Coming here, I quickly realized that America’s democracy has never really been tested and because of that, complacency can result.

When the president—the person who is president—was elected (it’s just difficult after so many years of Obama), I was struck by how quickly people rushed to find the bright side, or started to label as strategy what seemed to me unhinged ranting. Americans don’t like to be uncomfortable, and I think that’s linked to their optimism. There’s a lot I admire about that optimism. I mean, if you compare it to a world-weary European “woe is me, the world is dark,” obviously I prefer American optimism. But it can go too far, especially when it has to meet what I see as a dangerous administration. I got frustrated: This was not the time to look on the bright side. Democracy is fragile.

Things people said would never happen in this country are, in fact, happening. Not many Americans thought people would be scared to travel, to be at the airport. I have a friend who now has her green card in her bag everywhere she goes. She says, “You never know.” Carrying your green card everywhere says something about the new America. There’s very little cause for optimism.

TREVOR NOAH: My mom used to say, “Life will continue to teach you a lesson until you learn it, and the ultimate lesson will be death.” She talked to me about being a young man of color growing up in a world where the police could “innocently” take your life. She always said, “Learn the lesson now from me, when I’m the authority figure, before there is another that you have to deal with . . .”

Donald Trump is the stress test of America’s democracy. Sometimes you don’t realize your roof is leaking until a major storm comes. In that moment, some people say, “Well, I’m going to move now.” I say, “Now’s the time to start thinking about how to patch this roof, because I don’t believe that it’ll rain forever.” And I can’t ignore the fact that three million more people voted for Hillary Clinton than for Donald Trump. A complicated electoral system that’s a slave holdover gave Donald Trump the victory. I think the optimism I felt after the election has been reinforced in these first hundred days. Here is a nation where many people, I agree, were complacent. But since the election I’ve seen hundreds of thousands of women marching, hundreds of thousands of men joining them on marches. I’ve seen people marching and fighting for what they believe in, engaging with their politicians. I saw Americans protecting Muslims in an airport while they prayed. After 9/11, that’s something I never thought I would see. In that aspirational moment, people saw themselves as maybe being better or trying to be better. Sometimes optimism almost tricks you into trying to be better.

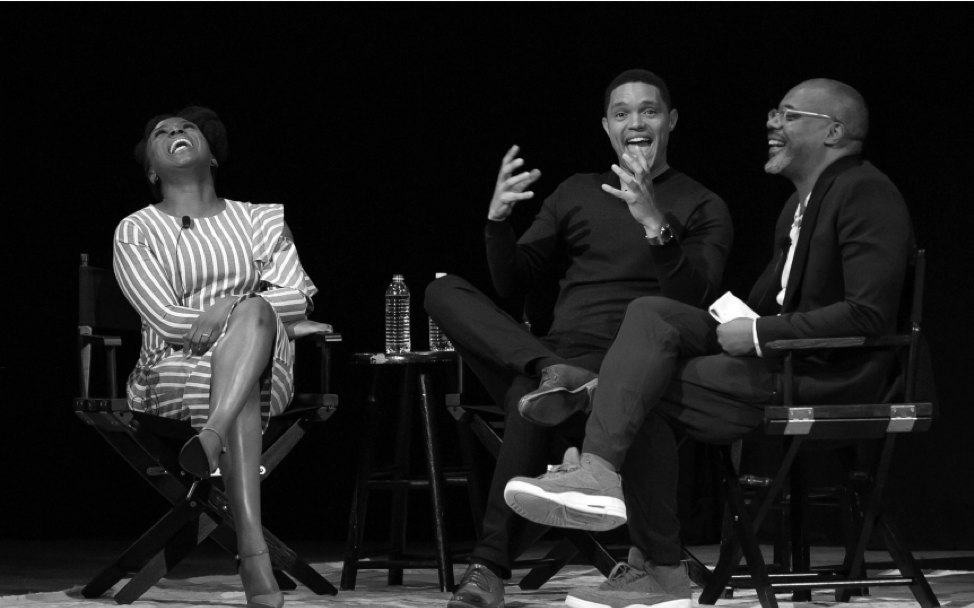

Photograph by Beowulf Sheehan/PEN America

ADICHIE: I respect that sentiment, but I bristled when I read Trevor’s piece in The New York Times because it made me think that we were taking a Pollyannaish approach to the election. It seemed to me the American president made himself relevant by mounting an utterly racist campaign to delegitimize America’s first black president. That’s how he made himself relevant. And then he ran for office and in the campaign he managed to speak about women in the most horrendous way, to talk about immigrants in simplistic, dehumanizing ways. It just seemed to me that he won and suddenly we were being told, “Try to understand him,” and “Let’s heal,” and I just thought, No. It seemed unjust that people whose humanity had been questioned were now being told: (a) It’s your job to understand this man, and (b) Give him a chance.

NOAH: Just so you know, she’s not talking about me right now—

ADICHIE: No, I’m not suggesting that at all. I wrote my piece two weeks after the election, and it seemed to me there was a sense of “What the hell are we supposed to do about this?” Resistance in democracy is a good thing; dissent is a wonderful thing. That’s happening now. A hundred days in, I see it. I don’t see a lot of what I found myself reacting to when I wrote that piece in The New Yorker. In the small community in Maryland where I live, I get invited to political meetings in people’s homes: “Come and let’s talk about the Republican congressperson we’re going to unseat.” That, I think, is what a democracy should be. Many people who haven’t been active in the past have become active.

NOAH: That’s maybe where my response comes from. On The Daily Show, I’m blessed to work with a wide range of people from different walks of life, different backgrounds. People who come together to help create a show. This allows me to live not just in my space but in a tiny community that I’m part of every day. Immediately after the election, I noticed a shift in people’s perspective. One of our female writers turned to me and said, “I feel like my country has betrayed me.” She said, “Now we change. We change now, right? This show changes?” And I said yes, because now we have a purpose. What I noticed in myself and in my staff and in the American people was a galvanizing of the spirit. A guy like Donald Trump wakes you up. Growth happens when you’re outside your comfort zone. Donald Trump has put America—has put the world—outside its comfort zone.

JACKSON: Chimamanda, you said that living in two different places gives you perspective. You’ve written novels that take place entirely in Nigeria, and then for Americanah you wrote a novel that takes place all over the world.

ADICHIE: It’s easy to write about places that you’ve been to. In talking about fiction, though, it’s hard to intellectualize choices because half the time, I don’t really know. With Americanah, I wanted to write something about the present. I wanted to write a contemporary story about love, but also about the kind of African immigration that I’m familiar with. In the narrative about African immigrants that’s common in the Western world, they’re fleeing poverty and war and catastrophe. Obviously those stories are important, but it’s not the story I know. I wanted to write about the people who are not dying, who have not been caught up in any war, who are dreaming of more and for whom “more” is America. It’s also the story of the African who, in his mother country, isn’t hungry, probably even has a job, but who makes the choice to leave and is suddenly washing toilets in London. I wanted to capture that because it’s the story of people I know and love. I’ve lived in this country for quite a few years off and on, and I’ve spent time in London, where I have family, so the research part was really easy. My sister-in-law, who has a sharp mouth, said to me, “Next time, if you want to write about us, just use our real names.” And I was like, “Wait, what?”

JACKSON: So, Trevor, how about for you? You became a star in South Africa, then you became a star around the world, and now you’re here. Has that changed your storytelling?

NOAH: When you travel from one country to another, you realize that what is offensive there is not offensive here. You realize that what is seen as a person here is not considered a person there. Then you start to see more and more connective tissue. Donald Trump is charismatic, and whether you like him or hate him, he knows how to command the camera. America loves entertainment, loves the show of it all. I came from a country where leaders are charismatic. The one president who was kicked out was a policy wonk and didn’t connect with the people: He was focused on doing the job, not on the show around the job. Donald Trump seems all too familiar to me.

JACKSON: Americanah takes different parts of the diaspora, particularly America and Nigeria, and shows places where they connect and where each is observing the other from a difference. Chimamanda, do you believe, based on your experience living in Africa and living here, that some kind of pan-African unity exists between cultures throughout the diaspora?

ADICHIE: Yes, I do. When you’re looking at it historically, a hundred years isn’t really that long. African-American history didn’t start on a slave ship, it started in Africa. There are black people in the Caribbean, black people in Africa, black people in Brazil, black people in Europe. It’s not just about skin color. I believe very strongly that there are cultural traditions that have been passed down, that have been diluted, as they should be, but there are strands. I think of myself politically as pan-African, my political worldview is quite pan-African. I care about what’s happening in Kenya, and I care about what’s happening in the Bahia region of Brazil. I’m interested in the way that certain Yoruba traditions have survived in Brazil, I’m interested in Afro-Colombians. I’m interested because there’s a familiarity. There’s something that I feel connected to. It’s nice to think of Americanah as pan-African.

The book is about ways in which we connect and reasons we don’t connect. Trevor and I have such different experiences because we grew up in such different parts of Africa. South Africa is as removed as it possibly can be from Nigeria. I think growing up in South Africa is to be aware of race as a present reality in your life. To grow up in West Africa, and particularly anglophone West Africa, is to be oblivious of race. Very much aware of ethnicity and religion, but race, no.

When I came to the U.S., I discovered I was black. It was strange, because of the sort of casual arrogance that most Nigerians are bred with. (The Nigerians here know this is true—let’s be honest, we’re owning it.) I remember coming here, and after the first essay we wrote as undergrads, the professor came in and said, “Who wrote this essay? This is the best essay and I want to know who wrote it.” I raised my hand and he looked surprised. It was a small moment, but I realized he didn’t think the person who wrote the essay was black. Later I went through a process of wanting to run away from that label of blackness. I would say, “I’m not black, I’m Nigerian.” I did this for maybe a year, and looking back now, I recognize that in some ways, even my reaction is an indictment of American racism. I remember when people would say, “Come to the Black Student Union,” I would say, “Nope, I will be going to the library.”

But then I started to read—and especially in this age of alternative facts, it’s so important to read. There’s no way that an open-minded person can read the facts of American history and not acknowledge the massive injustice. It was a political choice to take on the label of black: I’m very happily black. When I first came here I lived in Brooklyn for a few months, and there was an African-American man who once called me his sister. I was like, “Nuh-uh, I’m not your sister.” After I had done a bit of reading, I just felt ashamed. I wanted to find him and say, “I am so your sister, take me back.”

JACKSON: Trevor, did you have the same discovery or shift in how you felt racially identified when you came here?

NOAH: Because of the oppression in South Africa, I was used to a label. I was used to suffering from low racial self-esteem, something that many South Africans still have. For instance, if you drove a nice car into a petrol station, the attendant might say, “Ah, the white man,” and that implied, “Look at you, you’re doing well, you have achieved whiteness.” So white goes well, black does not. You had a stigma but you thought, I can aspire to the level of whiteness, I can live in the white area, I can drive the white man’s car, I can speak the language like the white man, because for so long that determined your success in South Africa. In some ways it still does. It’s funny, I had Nigerian friends in South Africa and I was shocked by how confident they were. I used to watch Nigerian movies with my Nigerian friends, and I was like, “Why aren’t you watching Hollywood movies?” And one Nigerian friend said, “I choose our movies and our stories and our music because that is what we celebrate.”

When I came to the U.S. I was shocked at how some of the things I had aspired to were frowned upon. I did an all-black comedy show called Chocolate Sundaes, and the introduction was like, “Yo, man, we got this brother from South Africa, we got this dude who flew all the way here, man, we got to show him some love.” I walked onstage and the people looked at me like I was going to introduce the guy from Africa. I started speaking and no one laughed. Later, I did a show and a friend of mine, Chris Spencer, came up to me afterward and said, “Hey, man, I like that you do black rooms, because a lot of comedians who do mainstream rooms don’t do the black rooms. Just be careful. Because if they don’t know you they might see you as uppity . . . because of how you speak, how you dress, people may perceive you as someone who does not want to be associated with black.” I have to be careful of what I share and where I share it, because where you give it away may create a completely different connotation.

JACKSON: That’s a really good point. As writers and performers who speak to these multiple audiences, do you feel that you have to be aware of the audience when you’re writing about different cultures? Do you feel that you’re speaking for a group of people? Do you feel that you’re maybe having to strip what you write so that people everywhere can get it?

ADICHIE: No, no. Particularly in fiction, no. When I’m writing nonfiction it’s a different creative process. If I write essays, I generally know—or like to think I know—what I’m doing. So in some ways I’m aware of who the audience is. When I wrote that piece after the election, I knew that I was writing for a primarily American audience. But fiction is something that I love, what I think is my life’s vocation. I don’t want to get to the point where storytelling is shaped by any consideration that isn’t my artistic vision. The way I throw Igbo words into my fiction—I have had editors who think that maybe I should use names that are simpler, more American. I grew up reading books set in Russia, with long names I couldn’t pronounce, and that didn’t get in the way of my connecting with the characters. Literature is a universal language because it is specific. As a reader, I know the books I’m drawn to are steeped in specificity. I’m troubled when people say, “Oh, you’re universal.” Universal can often mean that you’ve stripped your work of the things that really make it it. Someone suggested, for example, that since I had become well known in America it might be a good idea not to use the title of a recent book. It’s called Dear Ijeawele, a name that is difficult even for Nigerian people to pronounce. But it’s a name I love and I said, “Nope, that’s the name we’re using.”

NOAH: Comedians are always conscious of audience. I agree that you shouldn’t try to be global, if that makes sense. So I would argue that you are global because of who you are. You don’t have to try. If many people connect with your story, you’re global whether you like it or not. I understand running away from becoming stripped or commercial—

ADICHIE: I would love to be commercial. I was raised in an Igbo household, and there’s no Igbo person who doesn’t love the word commercial. So I’m happy with commercial. But I know what you mean.

NOAH: I’m saying that when it comes to being global, I’m Trevor Noah who grew up in South Africa. I had the opportunity to go to a school that was quite white and then changed, and we were the first group of mixed children who were allowed in. So I’m shaped by having access to a world that some people don’t. That is a piece of me now. Same thing with my mother. She has a grasp of languages that she bequeathed upon me and now I try to mirror her. Having a father from Switzerland who is white, that shaped a piece of me. And then having a stepfather who was black, that shaped a piece of me too. So everything connects, and that is my specificity. I come from a country where our forms of communication are so interlinked that we’ve created languages within languages. So when I tell stories, specificity is exactly what I’m going for. I was listening to Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers when I was a little kid because my mom would play their music. At no point did I say to myself, Who are these white people? I didn’t even know that they were white. I just heard the music and they were singing a story, and my mother was singing it, and so I was hearing it and singing it with her. She connected with the specificity of someone falling in love.

ADICHIE: When I was growing up reading Enid Blyton, it never occurred to me not to connect with her characters. I didn’t grow up with a certain kind of entitlement that my world was the only world allowed to be universal. I’ve heard from men, bless them, who say they’re surprised they liked Half of a Yellow Sun because a woman wrote the book. Young writers from groups on the margins are told that in their writing they have to give the reader some form of entry, which often means toning down their specificity. We still don’t live in a world where there’s just that natural assumption that everybody’s story matters equally. We still don’t.