The PEN Ten: An Interview with Poet Tsitsi Ella Jaji

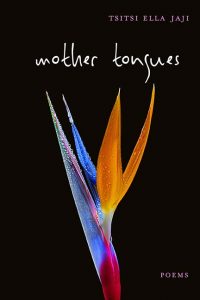

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Cave Canem, a national organization committed to cultivating the artistic and professional growth of Black poets, speaks with Tsitsi Ella Jaji, winner of the Cave Canem Northwestern University Press Poetry Prize for a second-book and author of Mother Tongues (Northwestern University Press, 2019).

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

I am going to answer these questions as a poet. I write scholarly essays and books for my job. I love that work but it is for my employer and professional life. I write poems because this pleases me, and my readers may do what they please with them.

Poetry is a mode of discovery—I don’t know my identity except through the writing, making, contemplating of it. Poems often surprise me, as if language leaks a truth I can’t find except by chance. But only if I show up, pay attention, read and watch and try not to flinch from the things that really sting. It’s why I sometimes feel that the time is the poem is out of joint…I find out why a particular poem came long after I wrote it, and that can sometimes scare me, sometimes goad me to write more. I lay bare the ways that my very language is laced with betrayals, experiments, a short attention span, grudges, silliness…the strongest impulse for me is to resist smoothness. The day I can only write in one “voice” will be the day that stumps me. Then what? I will begin again.

2. In an era of “alternative facts” and “fake news,” how does your writing navigate truth? And what is the relationship between truth and fiction?

For better or for worse, most of my poems grow from personal experience—something I see, hear, remember. I was raised in a robustly religious family where one got in deeper trouble for lying about a transgression than for the actual “sin” …so I just don’t have a good imagination for fiction. That isn’t to say that I want my poems to tell the truth without veneer. In fact, one major reason I choose poetry over prose is the capacity to cloak meaning in artifice. So, I get to tell my own truth, savage as it may be, and my reader gets to do whatever it is they care to do with what’s on my page.

“Poems often surprise me, as if language leaks a truth I can’t find except by chance. But only if I show up, pay attention, read and watch and try not to flinch from the things that really sting.”

3. Writers are often influenced by the words of others, building up from the foundations others have laid. Where is the line between inspiration and appropriation?

I have no idea. I earn my living as an English professor, and I have always felt acute embarrassment over never having taken a college creative writing class. But what I have gleaned comes from reading and discussing poems, and more broadly, texts of all kinds. I think a writer knows when they are crossing the line into appropriation, and there are certainly ethical stakes to such an act, but I do think that sort of theft can constitute a complex and serious artistic act. I may find it enraging, or politically malfeasant, but it is a work, it deserves attention, it deserves what it gets.

4. “Resistance” is a long-employed term that has come to mean anything from resisting tyranny, to resisting societal norms, to resisting negative urges and bad habits, and so much more. Is there anything you are resisting right now? Is your writing involved in that act of resistance?

Patriarchy. Womyn make up more than half of the human race. And people of color are the global majority. So, the way that it coerces womyn into infinite forms of labor, compliance, complicity, and silence has been a template for so many other forms of oppression. It stunts compassion as it authorizes a hoarding mentality, it refuses to face the fact that climate change is slaughtering our future generations because it puts the fortunes (literally) of “big men”, “big oil” and, let’s face it, would-be big dicks above the possibility of mutual accountability and balance.

5. Tell us about one of your most memorable moments experienced within the Cave Canem community?

5. Tell us about one of your most memorable moments experienced within the Cave Canem community?

Well, I have applied to Cave Canem’s workshop before and didn’t get in, but I feel like a distant cousin who shows up at family reunions every once in a while, always welcomed. This past year I was on a panel with Evie Shockley and she read her poem “supply and demand.” I am still shaken by it, a full year later. It captures in such detail and devastatingly clear quotidian language all of the ways that black boys are devalued in majoritarian U.S. society. My son was 3 months old at the time, and she, immediate auntie to him, had already crafted language into clasping these beloveds of ours as tight and despairingly as possible.

6. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

I wrote a poem in English that I translated myself into Shona. My Shona skills are not great, for reasons elaborated in Mother Tongues. I chose not to have the translation checked, to expose the limits of my knowledge of what was once my first language. I published it in an African online journal, Jalada. It felt embarrassing but honest to expose my linguistic dilemma. In another of my books, Beating the Graves, I included the same poem (from the VaNyemba Sequence) but this time I collaborated with my father on the translation. That, too, was true to something important, just a different way to mark the same ancestral departures and returns.

7. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What was your course of action?

My parents are navigating aging as an interracial and im/migrant couple. Recently, I wrote a poem about my father forgetting he had already given my mother a birthday gift, and how such faltering exhausts me even as I see the tenderness in their mutual care. I feel that they would be embarrassed to read it, that it is both a breach of their privacy and a declaration of my messy feelings. But the poem was honest, and I know these experiences are not limited to our family alone. So I did not do anything besides edit it to try and make it a better poem, craft-wise. It will be published in English Literary History, a pretty hefty scholarly journal, in a couple months.

8. Post, stalk, or shun: What is your relationship to social media as a writer?

All of the above, where Facebook is concerned. I am trying to wean myself from it, and it increasingly unsettles me on both a political and personal level. I find the Twitter sphere confusing and mean so I have posted only 4 or 5 times there and I don’t know my password. These other things like Instagram are for the youths. I wish them well.

“One major reason I choose poetry over prose is the capacity to cloak meaning in artifice. So, I get to tell my own truth, savage as it may be, and my reader gets to do whatever it is they care to do with what’s on my page.”

9. As a scholar, you have a special interest in “feminist methods and theories;” what are some ways this has formed the writing in your most recent collection Mother Tongues?

Oddly enough, most of the poems that have a dedication are addressed to men. But that’s nearly half our society, the half most in need of reform and alternative models, and when one encounters a humane and humble person’s work it can be feminist regardless of gender. Equally, ugly anti-womyn ways of being must be exposed, even when it is left to the reader to find what demands critique. A poem about domestic violence between son and father is a feminist poem. A poem about music that heals can be a feminist poem. A poem about insisting on surviving the likes of DJT must be a feminist poem.

But my overriding concerns are with womyn’s subjectivities, and the liberation of womyn-identified people to inhabit the full gamut of possible modes of freedom. Womyn do incredible, unmarked work, often as care workers, in domestic as well as other spaces. I am interested in naming and honoring what it is that allows us, despite differences beyond labeling, to stand “clavicle to clavicle” and fight for ourselves. A luta continua.

10. Which poets have had the most profound influence on your writing and what are some lessons their work has taught you?

How can anyone answer that question? I would start with Gwendolyn Brooks, whose attention to the private life of humble people ennobles them. Keorapetse Kgositsile does similar things, and builds bridges between music and word, just as he did between anti-apartheid and anti-black oppression in the U.S. during his exile when he connected with people in the Black Arts Movement. He taught me how simple diction can do sophisticated work. I started reading the work of my colleague Nate Mackey long before I had an office down the hallway from him. He has produced sustained work on a couple epics over decades—they are a model of mythography, rhythmic reorientation, song, and infrapolitics. I learn from the way he uses line, and lets recursive diction syncopate the poem’s gait in its own unmistakable meter. It is writing to mesmerize. I doubt I will ever write in an epic form, so it’s hard to explain what I have learned—I think at its core, his poems show how making myth can make entire communities of creativity gather and generate their own history, he inspires a vision of what makes artists pilgrims. Reading Petrarch and his contemporary soneteers in grad school was a wonderful window into how a poem can be a puzzle, interlocking, frustrating, yet unified. What I loved was that no matter how trippy the syntax or confusing the juxtapositions, the form promised that the poem would eventually fall into place. I don’t obey most of the rules of sonnets, but I often do find myself spending some of what they afford. But my favorite lessons are learned from Lucille Clifton. My husband gave me her complete poems for Christmas a few years ago…it was my second copy. The only other poet I have needed two copies of is Langston Hughes. Now I can mark one up Lucille book—when studying her and when composing musical settings of her poems—and keep the other one where I used to have a bible, by my bedside. Her family saga gives me license to write about my own family, and her work taps into the sacred while skirting its traps. Her poems are like dense yet lucid koans. Revelation.

Tsitsi Jaji is overjoyed to receive the Cave Canem second book award for Mother Tongues (2019). She is the author of Beating the Graves (2017) a chapbook, Carnaval, (2014). Her poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, Black Renaissance Noire, Jalada, New Coin, Harvard Review, Boston Review online, Poetry International, and the American Academy of Poets Poem-a-Day series. She has given readings at the UNESCO, Library of Congress, United Nations, and the Poetry Foundation, and has taught writing workshops in her home country, Zimbabwe. Jaji earns her living as an associate professor of English at Duke University, and is the author of a scholarly book Africa in Stereo: Music, Modernism and Pan-African Solidarity (2014).