Why We Need Stories: A PEN Ten Interview with Sophia Shalmiyev

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Camilla Bober, former PEN America Public Programs intern, speaks with Sophia Shalmiyev, who published her debut memoir, Mother Winter, this year.

1. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

The only way to maintain momentum is to have deadlines. I prefer to write lying down in my giant bed with my books and tea so I can dream and enter a private self without usual anxieties. My non-writing is largely dictated by the circumstances of my life. Am I severely depressed over a love affair? Is my dear friend going through a hard time? Do my kids need me to sign them up for summer camp? Am I behind on correspondence? Sometimes I just stare and think and take notes and cry and lay there in terror of not feeling clear, whole, or motivated until it’s juiced out of me and I can write again. Classic psychoanalysis couch stuff.

2. Whose words do you turn to for inspiration?

James Baldwin. “I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” America obsesses me, and I love her, too. I am Jewish and grew up believing that criticism is a form of deep passion, care, and sensuality. None of my romantic partners agree with this sentiment past the honeymoon phase.

3. What is the last book you read, What are you reading next?

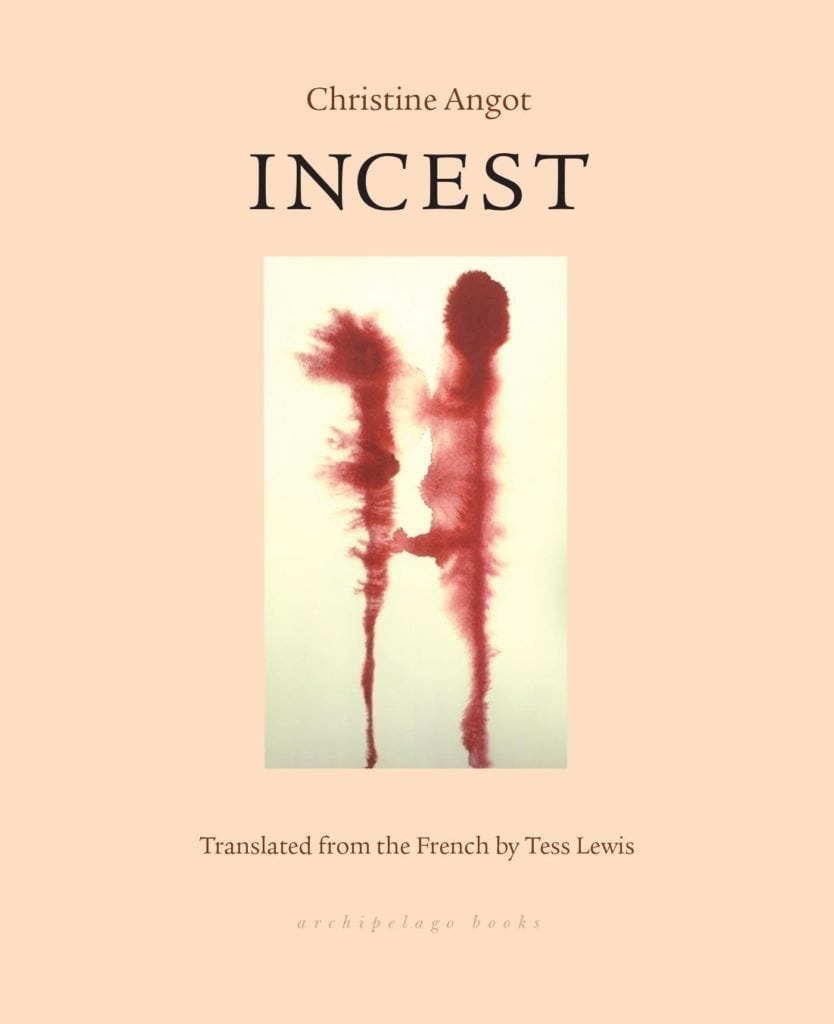

Incest, Christine Angot; translation, Tess Lewis and Without Protection, Gala Mukomolova

4. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

One of the biggest threats to expression is the personal, romantic, sexual, parenting, and domestic relationships female artists have with straight men. Many women (the probability for trans women is even higher) die at the hands of their intimate partners; get raped, get emotionally, economically, and physically abused. On the other end of the danger spectrum, our politeness, our invisible gag orders, our sexist literary communities, our fear of never having a fun, solid, and stable mate who shares a feminist vision with us are all preventative measures for achieving our goals. We become resented and resentful coaches and therapists while shortchanging our own desires, place in community, and art making. I can’t work as hard as I want to on my novel if I am having panic attacks over the entire reproductive bag of pregnancy and abortion to hold with no support, along with the political discourse and labor that goes into protecting my rights, while the men nurse a beer and warm up a barstool and chill. The war on our bodies has never ended.

5. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

“I am forty now and am so very tired of the male expert. He doesn’t ask any questions out of a genuine need to understand. It is all macho diarrhea couched as intellect or recital of lines. Why are they fans and we are groupies?” (Quote also mentioned in Girl Crush interview, by Ellie Piper.)

“We exist because so many before us dared to subsist on crumbs . . . “

6. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I have said or written things that were censored and cut away or not aired in a podcast or on the radio. And I regret that because we need to be less clean and tidy, especially us irreverent women who deal with shame on a daily basis. Really makes me feel like more of an alien, immigrant, and outsider all over again.

7. What advice do you have for young writers?

Watch out if you are a young woman and you have a male boss. Or any dynamic where men have power and authority and will sexualize you. Create communities, jobs, and literary salons that aren’t sausage parties, nor gotcha culture cauldrons. Above all, writers are in this to read and commune with voices which resonate, uplift, challenge, and encourage. We are interdependent and derivative. We exist because so many before us dared to subsist on crumbs and got beaten down, erased, and died of AIDS, for example. If we don’t pay our respects and keep their light alive we are killing our own true futures in the service of narcissism and capitalism. Read Valerie Solanas alongside Freud and see for yourself what we can lose. Counterintuitive to that, my advice is for caretakers to get selfish with their time and band together to encourage a domestic revolution so that writing can actually take place.

8. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

Always Eileen Myles and CAConrad; they are true geniuses. Robert Lashley, Kate Zambreno, Leni Zumas, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, Sarah Schulman, Rebecca Solnit, Chris Kraus, Sara Ahmed, Christine Angot, Veronica Gonzalez Peña, Janet Fitch, Masha Gessen, Svetlana Alexievich, Warsan Shire, Constance DeJong, Cooper Lee Bombardier, and Amy Hempel.

9. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you discuss?

The answer will forever be Grace Paley. I feel a kinship and a twinning with her as a Jewish, feminist, urban, single mother of two, and writer at a later age, though I am not even in her orbit of dedication and talent and political engagement. I would discuss ex-husbands, public schools, affordable housing, and poetry with her. I named the character in the novel I am writing after her to give it courage, wit, and humor; to bring her in the room and make a new woman who isn’t punished harshly for her mistakes, even if she isn’t “likeable.”

10. Why do you think people need stories?

I imagine it’s the same reason we need mothers. It’s a container and a vessel to draw from and add into and safely reject to become who we, sometimes grandiosely, believe ourselves to be.

“The kind of writing I believe we need more of is jagged, way stranger, and structurally embodying the thinker, the visionary, the hermit, and the loudmouth—a hybridity of bodies and sensibilities on the page.”

11. Your memoir reminds me of a mosaic: all of these bits and pieces of identity come together to create one cohesive picture of yourself, but when you look closer you still see each individual piece separate from the other. How can memoirs, as a genre, be used to create one image of a collective, human identity and encourage empathy?

This encouragement of empathy is critical in combating violence and violations, I believe—what Anaïs Nin has given us in her work—an evolution, a way of writing that is not an imitation of what the men before her were saying or doing, but a deep excavation of the ping pong and toxic sludge between a male-ruled society and the feminine being. I don’t need an arc. I don’t care if your book has a plot. I want to understand how the gears were covered by cement and if we will ever see them move again. I battle fragmentation and a culture that has never allowed me to belong or relax and so the characters I write, the voice of my narrator, the construction of the text, those will always be about a mending and a hinging of orphan pieces. The kind of writing I believe we need more of is jagged, way stranger, and structurally embodying the thinker, the visionary, the hermit, and the loudmouth—a hybridity of bodies and sensibilities on the page. I respond to problems. That’s writing to me. So is feminism, at the core. It is asking for accountability—a measure of worth that isn’t a trick scale for arranging our stories on the side that’s currently suspended way up high, seemingly out of reach, against all odds. There is a seed buried in the crack of your tooth you can’t get out, no one believes it is there, and the chapters are the pick, the floss, and maybe even the chisel.

Sophia Shalmiyev emigrated from Leningrad to America in 1990. She is a feminist writer and painter living in Portland with her two children. Mother Winter (Simon & Schuster, 2019) is her first book.