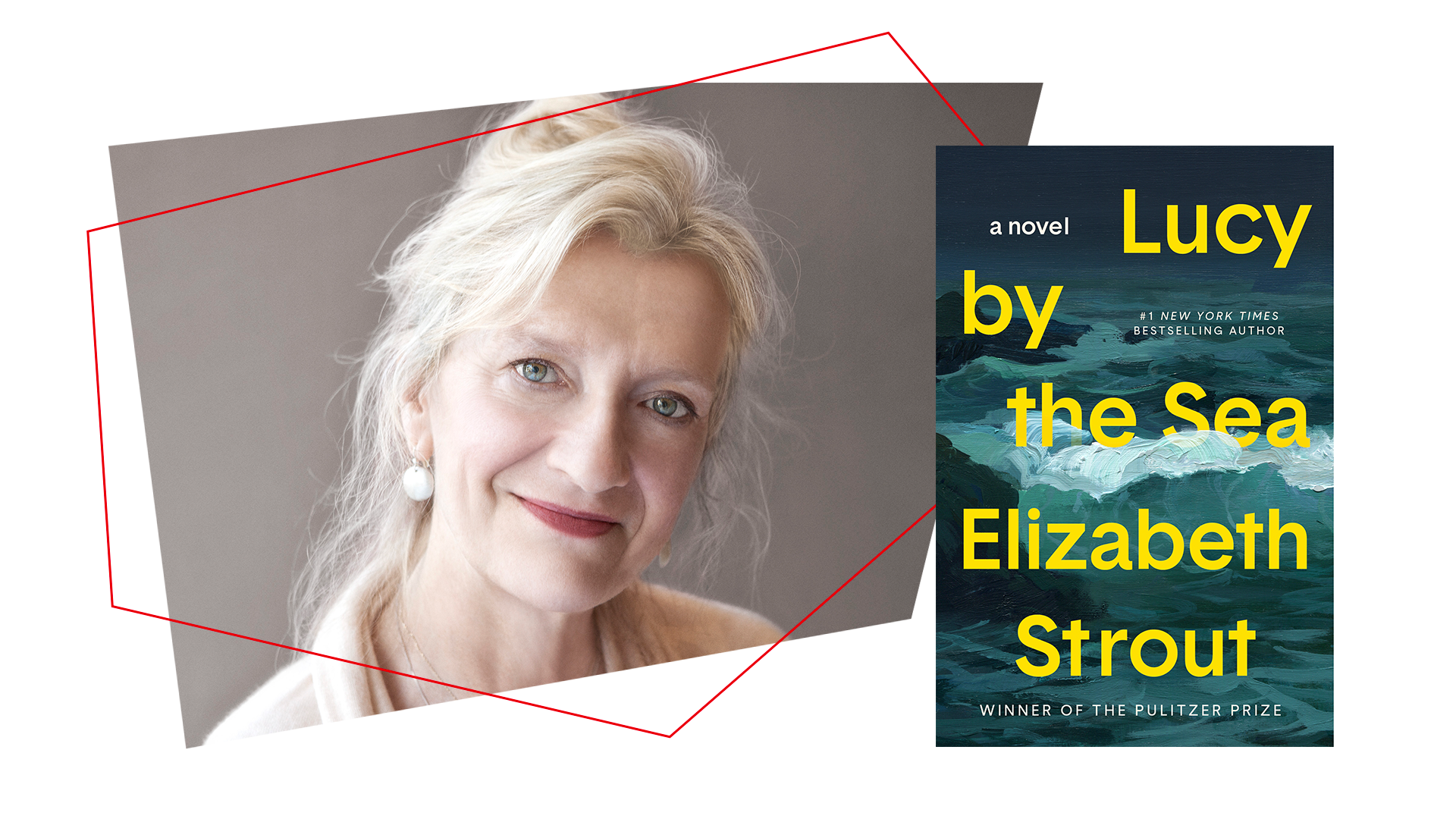

Elizabeth Strout on Writing: ‘Just keep going.’

'It’s never easy. But it is sometimes fun. And when it's going well, there's nothing like it.'

By Lisa Tolin

At 66, Elizabeth Strout is turning out books faster than ever, and no global pandemic could slow her down.

Her latest novel, Lucy by the Sea, is fast on the heels of her Booker Prize-shortlisted Oh William! and follows the characters first introduced in My Name Is Lucy Barton through the pandemic.

Strout says she honestly doesn’t know how she’s become so productive at an age when many people might consider retiring.

“I think that there’s just a sense of having prepared for a marathon for so many years, and now I’m running it, you know?” she says. “That’s my sense, because it just keeps coming out, and I do know more what I’m doing now, a little bit.”

Her marathon training involved a string of unusual day jobs and piles of rejections. She kept the rejections in a box but never counted them, and threw them away when she published her first novel at 42.

Even now, she says, writing is never easy. “No, it’s never easy. But it is sometimes fun. And when it’s going well, there’s nothing like it.”

In conversation with PEN America, Strout reflected on Lucy by the Sea and life as a writer.

Early on in Lucy by the Sea, Lucy thinks she will never write another word again. But obviously, you were quite productive during the pandemic. Did you ever have that moment?

No, because I just always seem to be writing no matter what is going on in life. I mean, I have certainly had points where I think I’ll never write again, even as I’m writing, you know. But I just thought Lucy would feel that because she’s been so disrupted from her life, as she’s known it, that I thought Lucy would feel that.

Did you feel that writing about the pandemic as it happened was therapeutic for you?

Oh, it probably always is. I mean, it’s funny because I’m working on another book and I thought, “Why do I always keep doing this?” And I thought, “Well, it’s just what I like to do.” So, I mean, I guess it’s probably always therapeutic for me in a way to be writing. I haven’t really thought about it, but it’s just something I just seem to always do. So, there was a pandemic staring me in the face. And I thought, “Well, I can’t pretend it didn’t happen, so let’s write about it.”

“There was a pandemic staring me in the face. And I thought, “Well, I can’t

pretend it didn’t happen, so let’s write about it.”

You returned to many familiar characters. Do these characters live in your head at this point and walk around with you?

You know, I think they kind of do in a way. I mean, they must or they wouldn’t just keep reappearing. I think that when I write somebody, I just get to feel that I know them so deeply or I wouldn’t be writing them, that they stay with me. You know, they just end up staying with me, because I feel like I’ve really gone so far into their minds or their souls or whatever.

The concept of having a divorced couple thrown together during the pandemic is so instantly compelling. How did you know you wanted to come back to Lucy and William?

I had literally just finished Oh, William!, when the pandemic started. And honestly, I even thought about making it be an epilogue, because nobody knew – I didn’t know how long it was going to last. And I thought, oh, maybe I’ll just do an epilogue. … But then I was so pleased with the way Oh William! finished that I didn’t want the reader to turn the page and have to find the same voice going on. And then it turns out that it was its own book because, you know, the pandemic kept going on.

You knew from a very young age that you wanted to be a writer. Was there a moment of revelation?

I think I was a junior in high school and I remember telling my mother I was going to be a writer. So at that point it certainly crystallized, and I remember she said, “Well, you’ve always had an excess of words.” (Laughs)

Mother-daughter relationships are something you explore a lot. Has your perspective changed as your own daughter grew up?

Well, I can only say that I have had a very, very complicated relationship with my mother. And for me to have my daughter was so restorative and wonderful. Just the biggest gift of my life, frankly, my daughter has been. And so as I get older and realize, you know, how much real nurturing and care can do for somebody, I’m not surprised, and I’m not sorry for the books I’ve written. I guess that’s what I’ll say.

You had so many interesting careers before you published your first novel. You were a lawyer, a waitress, a piano player, you worked in a mill. Did that experience enrich your writing?

Yes. It took me years to realize that, but absolutely every single job I had – and I had so many really awful little jobs – but I think that every single job, I learned something about different kinds of people. If I hadn’t worked in that office room of the shoe mill, I would never have been able to write Amy and Isabelle. And I got to know so many different kinds of people throughout the different jobs that it just opened up many, many worlds to me, frankly.

I’m particularly fascinated by your time doing stand-up comedy.

Ugh. God, I was so frightened.

What prompted you to do that?

I was interested in comedy. Ever since we moved to the city, we’d go to the different comedy clubs. And what struck me is that people laughed when something was said that was true. And I remember thinking at that point in my poor little writing career that I just felt like there was something that I wasn’t being honest about, but I didn’t know what it was. I couldn’t figure it out. And so I thought to myself, “What would happen if I put myself in that kind of pressure cooker situation of, whatever came out of my mouth had to be true enough to make people laugh?”

So I took a standup comedy class at the New School, and that was frightening enough. Every week somebody else dropped out, but I stuck through it. And then those of us who made it through, for our final exam, we actually had to perform standup comedy. And it was so, so terrifying for me. Oh, my word. I wouldn’t let anybody come. But this guy laughed, and then everybody else started laughing, and I will never forget it. I just love him, whoever he was. God bless him.

“My instinct was right to do it, but it was absolutely terrifying. I swear

it took at least two years off my life.”

But the point is that it did work, because my whole thing was about making fun of myself as sort of an uptight white woman from New England. And the truth is, honestly, until I did that, I did not even know that about myself. I didn’t even know that I was a white woman from New England. That’s how white I was. That’s how New England I was. I just didn’t even know it in a certain kind of way. And then when I realized that, I thought, Oh, okay. And then I was able to write Isabelle Goodrow, who’s a very uptight white woman from New England. I mean, she’s not me at all. But, you know, it was grounding to me to realize, oh, that’s my place in this country.

So it helped you get in touch with yourself.

It did. My instinct was right to do it, but it was absolutely terrifying. I swear it took at least two years off my life.

You also endured rejection, even as you were having some success. What would you say to someone going through that kind of rejection now?

Well, it’s not fun. There’s nothing fun about a rejection. Ever, ever, ever. And then just forget about it. Keep going. Just keep going forward, and keep writing your best work that you can at the time that you’re writing. Just make it as good as you can and just continue to do that. You have to swallow the rejection, but just keep going. Keep going.

You have compared your writing process to uncrumpling wax paper or pressing on chewing gum. Can you talk about what that means?

Well, I mean, I don’t know why that bubble gum thing comes to mind or even really the wax paper, except I do – but it’s always just a big smudge. And then I’m trying to smooth it out. Every time I go back and back and back, I try and smooth it out. And I write by scenes. I don’t write from beginning to end. And so every scene I try and smooth out, if it’s got what I call a heartbeat to it, if it’s worth it, then I will go back and keep smoothing it out and then, you know, adding to it or, or another scene will automatically somehow sit next to it. That’s pretty much how I write, actually. It’s interesting. I mean, it’s interesting to me. (Laughs)

At some point, it must be like assembling a puzzle.

It is. That’s a good way of putting it, because I do have all sorts of different scenes, and then I stick them away. And then I’ll all of a sudden remember, “Oh, wait, wait, wait. Let’s find that scene. I bet that would go there.” And if it does, it’s, you know, thrilling.

What’s the last great thing you read?

The last great thing I read was Richard Yates. I read both Revolutionary Road and Easter Parade, which I had read years ago, and I reread them, and I loved them just as much as I did the first time. I don’t know why he is so compulsive to me.

What’s the best advice on writing you’ve received?

The best advice on writing that I received was probably given to me by myself, which is to just keep reading and keep writing. Just do not stop. That’s what I understood years ago. I don’t think anybody ever told me that. I just figured it out. But I think it’s the best advice that a person can have if they’re trying to be a writer.

What do you hate about writing?

When it doesn’t go well. It makes me feel awful.

Do you still have those days?

Yeah, I do. But you just keep going. You just keep going. And that’s why at this point, it doesn’t matter as much as it used to because I realize, “All right, so I just wrote really badly today. Tomorrow I won’t write so badly.” And then if I do, I just keep thinking, “Well, tomorrow I won’t write so badly” again, and then eventually, I don’t write so badly.

Lisa Tolin is Editorial Director of PEN America. Her debut picture book is How to Be a Rock Star (Putnam, 2022).