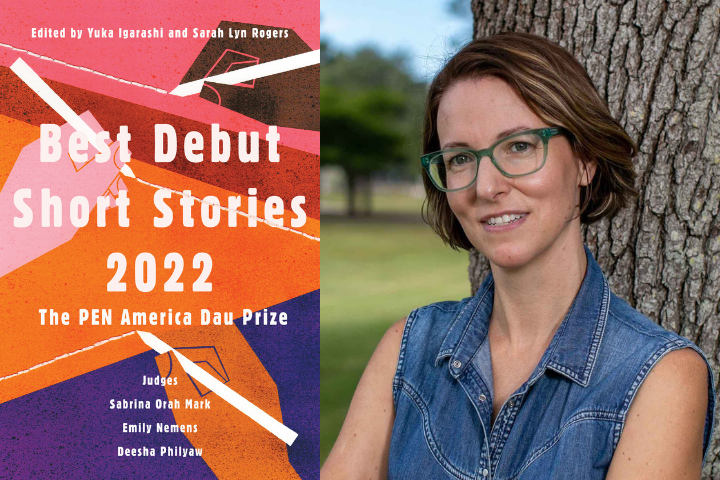

An Interview with PEN/Robert J. Dau Prize Winner: Erin Connal

In the upcoming weeks, we will feature Q&As with the contributors to this year’s Best Debut Short Stories anthology published by Catapult. These stories were selected for the 2022 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers by judges Sabrina Orah Mark, Emily Nemens, and Deesha Philyaw.

Erin Connal is an Australian-born writer who has lived half of her life in the United States. She earned her MFA at NYU, was shortlisted for the 2021 Disquiet Literary Contest, and was a runner-up in the 2021 Northwest Review Fiction Contest. She has been published in Virginia Quarterly Review and in Northwest Review. She lives in Honolulu with her family and is currently working on her first novel.

“The Black Kite and the Wind” was originally published in the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Here is an excerpt:

The Brighton Beach fire was a great success. The hedge was destroyed and we spent time in plain sight of the house on the beach the following week, turning our bodies like rotisserie chickens to ensure an even suntan. People walking by stopped to see the damage. The fire had melted the top of the post that held the net for their clay tennis court so that its shape had distorted. It looked like a charred candy cane. The house itself, glazed, modern, and all right angles appeared naked. The facade of the second story was floor-to-ceiling glass and so all of their belongings, expensive furniture, and walls adorned with artwork were on display. The whole house and its occupants seemed violated by the public gaze that we, and the rest of the city, were afforded once the hedge was razed.

“The Black Kite and the Wind” evokes a dry summer in the Australian bush. Living in the USA, how did you connect with that landscape when you were writing?

There is not a day that I can’t connect with the landscape of Australia. I grew up in an Australia that revered its nature and around people who embraced spending time in it. It’s a place that no longer exists. It perhaps never did exist in the way that I have idealized it. The smell of the air—pure, smoke-streaked, eucalypt perfumed—is indelible within me. I think it also helps to have left. When you leave a place your mind makes a time capsule of it, the memories are tied to smells and other sensory triggers, and everything is concentrated. The effect is a sort of reverence and a kind of trauma too. Whenever I go home, I find myself overcome with an urge to kneel down, to bury my hands in the dirt, the sand, and the sea. To be covered in the place itself and to breathe it in. It’s not something I’ve ever felt anywhere else.

What advice would you share with aspiring writers?

My big-picture advice for aspiring writers is simply to write. All you have to do to be a writer is write. You will spend your life the way you spend your days, and if you spend time writing every day (or 5 days a week) you will produce pages and you can call yourself a writer. Routine is key. Also, something that was driven into me by one of my teachers that I have found essential, is to never research while writing. Never be tempted to look up something when you’re in your groove. Put a placeholder and come back to it later. Ideally, write without an internet connection. And if writing in public always pack headphones to tune out the noise. Unless you need dialogue inspiration, in which case eavesdrop and take notes.

What do you hope readers take away from your story?

I wanted to explore the slippery space that misbehaving as a group allows us. The story is about a group who does something terrible but the individuals in the group never take any personal responsibility. This neotribalism plays out differently in different places. In Melbourne, when I was growing up, it was about which high school you went to, which ‘natio’ you were (the second-generation kids might claim their parent’s heritage, Greek, Turkish, Italian, Vietnamese, etc), and which football team you supported. I wanted to explore the female, teenage, intellectual, and privileged tribe. A group made aware of their privilege only recently, who are all of a sudden morally compromised by it. I suppose a takeaway might be that if membership in a group empowers an individual to misbehave, perhaps being alone isn’t such a bad thing after all.

What inspired you to write this story? Where did the idea come from?

I started to write The Black Kite and the Wind in Paris in the winter of 2019. In Australia it was summer and the bushfires were making headlines worldwide. I was at NYU Paris and had workshopped another story that wasn’t working. In the other story there was a male character who was carrying a burden from his past that I had alluded to but never fully explored. I met my thesis advisor and we talked about home. About the environment, the heartbreaking images that were on the news. Fire seemed like the only possible thing to explore. I began writing about the kids lighting fires as backstory for the male character and quickly realized that these weren’t boys wreaking havoc, that this was an entirely different story. I read J. G. Ballard’s novella Running Wild when I was quite young, probably too young, and it has stayed with me. And fed up with stories—whether they be in literature, on television or in film—that begin with a dead female body, I had been wanting to write a story in which the girls are the ones who do the killing.

How has the Robert J. Dau Prize affected you?

The prize has bolstered my confidence and encouraged me to continue with my writing. I am working on my first novel and am tinkering with other stories to add to a book-length collection. The day after I went to New York for the ceremony I met with some amazing agents and ultimately signed on with my dream agency. Winning the Dau Prize remains a surreal and inexplicable surprise and being able to hold the collection as a book in my own two hands is the thing of a dream.